Original: 【聲援CIC黑獄絕食第17日人士 停止無限期關押】, published in Grassmedia Action

Translator: Grassmedia Action

This article has been edited for precision and clarity. If you would like to be involved in our translation work, please get in touch here.

On 29 June 2020, over 20 detainees from India, Pakistan and numerous African countries embarked on a hunger strike to protest their unexplained indefinite detention at the Castle Peak Bay Immigration Center (CIC). Strikers have been detained for anything from two months to nearly two years, out of whom six have been held for more than one year. Some of them are rehabilitated offenders, and many were released from prison on good behavior in the past. Others are awaiting results for asylum applications or appeals.

Today marks the fourth week of the hunger strike. The number of strikers has now increased to 28, and some have escalated the action by refusing water; one has already been sent to the hospital. So far, the Immigration Department has remained indifferent. Some immigration officers have reportedly told strikers to “keep waiting.” One officer has repeatedly remarked, “If you refuse to eat, you should just die.”

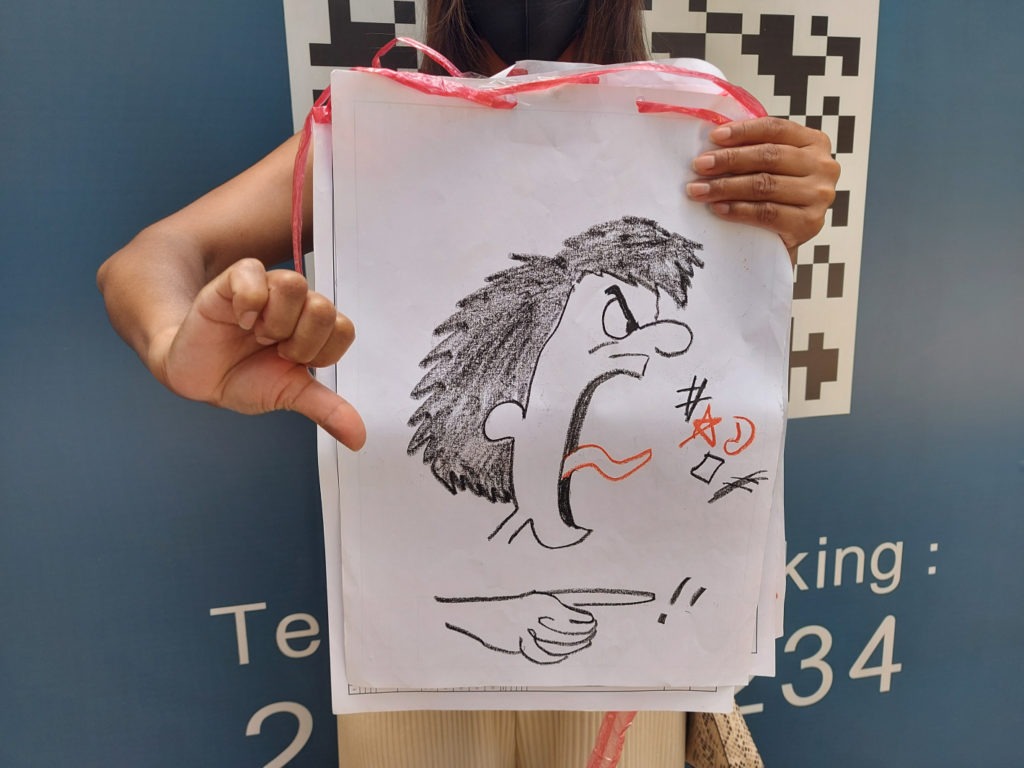

On July 15, CIC detainees’ right concern group (a.k.a. CIC Concern Group) and volunteers gathered outside the Immigration Tower in Wan Chai to stand in solidarity with the hunger strikers. Together with friends and family of the strikers, former detainees, and other supporters, the organizers presented a “gift” to Au Ka-wang, the newly appointed Director of the Immigration Department: a cake bearing a reminder (新官上任,請積陰德) for Au to uphold human rights and carry out his office with integrity and modesty. They asked the Director to think twice about celebrating his promotion while detainees put their lives on the line to demand basic rights from his office. The Director refused to accept the gift.

The protest was also disrupted and eventually ended by the police while speakers were in the middle of making their statements. Organizers had complied fully with public health regulations that limit public gatherings to groups of four.

Wilful neglect of medical needs

While the Immigration Department claimed that the physical and emotional condition of the hunger strikers is “more or less stable”, strikers appeared very weak when the CIC Concern Group visited the facility over the weekend. Some of them have started having persistent headaches, while others are reporting short-term memory loss. Requests to see a physician continue to go ignored. Fish, a member of the CIC Concern Group, described the strikers as “extremely desperate.” Two of them have prepared suicide notes; one even told his mother that “her son is as good as dead.”

The lack of medical attention is currently the biggest concern for strikers. One striker has a tumor in his left arm. During a stint in prison in 2015, he was at least allowed to visit Queen Mary Hospital once a month and was able to get his prescribed medicine. In the CIC, however, the doctor never gives him what he needs. Instead, he keeps receiving the same ineffective drug that has done nothing to improve his condition.

‘Can you imagine? He has lived in Hong Kong for 26 years without returning to India once. He’s now over 50. Nobody knows him back in India. His family and friends are all here in Hong Kong.’

According to the experience of many detainees, the CIC doctor issues Panadol (Acetaminophen) no matter what the illness is. An Indonesian detainee lost two fingers inside the CIC due to the lack of appropriate medicine even after her fingers had been surgically reattached. She was given only Panadol.

This flagrant neglect of detainees’ medical needs is made worse by the abject hygiene conditions in the CIC. The facility is infested with rats, and sanitation has remained low on the list of priorities despite the city’s new wave of COVID-19 cases.

A broken immigration system

Li Ka Singh is a close friend of Harjang Singh, a hunger striker from India in his fifties. He told the public that during his visit last week, Harjang seemed “very unwell.” Li Ka is worried that he can no longer afford to carry on with the strike.

Born and raised in Hong Kong in 1981, Li Ka Singh speaks fluent Cantonese. He likes to introduce himself as “Lee Ka Shing” (a Hong Kong billionaire) as he is fondly known amongst his friends. At the age of 18, he met Harjang Singh in the Khalsa Diwan Sikh Temple in Wan Chai. The two became fast friends. At the time, Harjang was in his twenties. He migrated to Hong Kong in 1996 with his mother and has been working here ever since. He met his wife, a Hong Kong permanent resident, and gave birth to his daughter in Hong Kong. During the required 7 years toward obtaining permanent residency, Harjang was convicted and sentenced to jail in his fifth year of stay. Thereafter, the Immigration Department cancelled his right of abode in 2005. Harjang sought asylum in Hong Kong, fearing death threats once he returns to India as a Christian convert. He was granted a recognizance paper (行街紙).

As a rehabilitated offender, Harjang was still detained in the CIC for two years after serving his time in prison. Li Ka criticizes, “It’s totally unfair. Why can’t a person be released after serving his sentence? The Immigration Department has no reason to detain him. Is he a dangerous person? The Department made no explanation. Two years behind bars for unknown reasons can make anybody mad.” He hadn’t even learnt about the terrible conditions in the CIC until some of his friends, who happen to be ex-detainees, shared their experience with him.

‘No one is born bad. The system is what ensures that we turn bad and stay bad.’

Though Li Ka and Harjang are both Hongkongers who have raised their families here and been an active part of their community, only one of them can stay. The other now has to leave because of the lack of a Hong Kong ID. Li Ka finds this exceptionally unfair, “Can you imagine? He has lived in Hong Kong for 26 years without returning to India once. He’s now over 50. Nobody knows him back in India. His family and friends are all here in Hong Kong.”

Currently, Harjang’s lawyer is lodging a judicial review against the Department’s order of removal. Meanwhile, he is facing a deportation order that will forbid him to visit Hong Kong ever again. The torture claim he has filed is still being processed.

Mr. Vhagtsingh from the Bhagt Singh Sikh community in Hong Kong gave a speech during the protest. As an Indian born and raised in Hong Kong, he believed he and other Sikh friends are part of Hong Kong. He used to have faith in the system, “If one commits a crime, he must receive punishment. Then, he should be free.” However, the CIC has revealed how broken this system really is. Vhagtsingh couldn’t believe there are such serious human rights violations in the city. He urged the Director of Immigration to release the detainees immediately, “No one is born bad. The system is what ensures that we turn bad and stay bad. So please, everybody, give these people a real chance to become good.”

Volunteers and ex-detainees visit hunger strikers

Last weekend, the CIC concern group gathered a group of volunteers to visit the hunger strikers to stay abreast of their situation. Tony is one of these volunteers. It was the first time he had ever entered the CIC. As he has never met his striker before, he could only rely on what he remembered from a photo briefly shown to him by an immigration officer when he went through a registration process at the CIC. But the person behind the glass wall in the visitation room was beyond all recognition; he has become much thinner than he appears in the photo.

The detainee in front of Tony is an Indian whose torture claim was rejected. He had lodged a judicial review against the verdict, but has still been detained for one and a half years. He said officers have split the hunger strikers off from the rest of the group in small rooms, so that other detainees remain in the dark about the action.

The visit was made on Sunday. Just a day ago, one of the strikers had fallen ill; he asked for a doctor for five hours to no avail. During the visit, Tony recalled that he sometimes couldn’t catch the striker’s words, probably too weak to speak up or repeat himself. He already seemed to be doing better than some of the others.

‘I support the current detainees because I’ve suffered there myself. I know how difficult it is inside the CIC. There is no humanity… The problems remain the same, and this time it’s the hunger strikers who have continued the struggle. We need an answer.’

Another volunteer, Miss Fok, visited a Pakistani hunger striker. He sought asylum in Hong Kong in 2007, but was intercepted by the police in a taxi in 2014 where drugs were found. Although he told the court that it was the taxi driver who had possessed the drugs, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Due to his appeal and good behavior, he was granted a release after 6 years.

On the verge of long-awaited freedom on May 23 this year, the striker was abruptly sent to the CIC. Multiple requests for bail have gone in vain. He feels anxious inside the CIC. When he asked for medical treatment, the CIC doctor would only briefly check his blood sugar levels. Detainees’ health condition is the least of officers’ concern, he said.

Miss Fok had left her contact details during the visit, and received a call from the striker three days later, expressing gratitude for her visit. She felt conflicted when she received the call. Although she was moved, she knew detainees can only make one 3-minute call per week. She felt guilty that what she has done to help is very minimal—she couldn’t even pronounce the striker’s name correctly. Nevertheless, the striker emphasized that he would keep going with the strike with the support of the volunteers.

S, a Nepalese ex-detainee, was the “CIC guide” in the team. While she was seeking asylum in Hong Kong to find refuge from the Nepalese civil war, she was arbitrarily detained twice. The first time had been for 4 months, for which she was awarded damages for illegal detention. The second lasted 3 months and 21 days. She was just released at the end of 2019.

Since her release, S has actively lobbied for media coverage of the poor conditions inside the CIC and reached out to lawyers to discuss possible legal action. She got in touch with the CIC Concern Group earlier this year. What followed was her participation in a range of solidarity actions, including weekly visits to the CIC, distributing leaflets on detainees’ rights to visitors, collecting questionnaires on detainees’ conditions and grievances.

Once she got wind of the hunger strike, S joined the July 5 protest action with relatives and friends outside the CIC. Last weekend, she led the volunteer team to visit 20 hunger strikers, explaining the procedure for social visits and articles allowed in. “I support the current detainees because I’ve suffered there myself. I know how difficult it is inside the CIC. There is no humanity… The problems remain the same, and this time it’s the Indians (hunger strikers) who have continued the struggle. We need an answer.”

Migrant and sex worker advocates speak up

Midnight Blue, an organization supporting male sex workers, has participated in several protest actions in support of the hunger strikers. According to Kin, the executive officer, Midnight Blue has followed around 60 cases of detainees in the CIC since 2013 who are transgender sex workers. Hong Kong laws provide no protection for sex workers—even though sex work is not illegal—but workers have nevertheless been targeted and criminalized. For instance, foreign sex workers are usually charged with “soliciting for an immoral purpose” or “breach of condition of stay.”

Once arrested, transgender workers are sent to Siu Lam Psychiatric Center, a maximum security facility run by Correctional Services. As they are mostly from Southeast Asia, what awaits after their sentences is deportation. Before they get deported, however, they are detained in the CIC. Since officers typically refuse to deal with sex beyond male and female, trans detainees have instead been confined in solitary, which is tantamount to torture. As transgender ex-detainees recall, the strong light in the cell made it impossible to fall asleep. Except for the allotted 10 minutes for showers, they were not allowed to move around at all. Nor were they permitted to speak to other detainees. Sanitation levels were again despicable. There was excrement everywhere but no one would clean it up. “A day in the CIC is more suffering than a month in Siu Lam,” they said.

When trans workers are detained in the CIC, Midnight Blue organizers try their best to book flights for them to leave as soon as possible. Otherwise, it will take at least 1 to 2 weeks for the Immigration Department to buy them tickets. However, this is never a welcome move for officers, Kin added. They will even persuade Midnight Blue not to buy the tickets themselves. Kin suspected that this complicates their administrative procedure, such as increasing the amount of paperwork they have to file.

Since officers refuse to deal with sex beyond male and female, trans detainees have instead been confined in solitary, which is tantamount to torture.

Some trans workers are also asylum seekers. They seek asylum in Hong Kong as their identity have been met with death threats in their own countries. Nonetheless, compared to the stories he has heard in the recent actions, Kin believed the workers they know are relatively lucky. At least they can still be released with a recognizance paper, though that usually happens after at least a month of detention.

Sophie is a migrant justice activist who is involved in local anti-establishment movements. In her speech, she said many Hongkongers might have once regarded jail sentences or prisoners’ rights as something distant from their daily lives. Yet, for many people, experiencing the anti-extradition bill movement last year must have shed light on imprisonment as a tool utilized by the authorities to suppress dissent. Just as protesters have shown compassion for over 9,000 comrades, either in prison or losing their freedom in other ways, everyone should be able to understand what the hunger strikers in the CIC are going through. No one’s freedom should be violated, Sophie stressed.

The inhumane treatment inside the CIC is shameful. For Sophie, what is most outrageous, however, is the fact that these detainees are never even supposed to be detained; many of them are asylum seekers. They sought asylum because of war and political or religious persecution in their own countries, just like a lot of Hongkongers in exile today. She remembers Ray Wong’s (a Hong Kong independence activist, one of the founders of Hong Kong Indigenous, currently a refugee in Germany) account of his one-year detention in a refugee camp and its serious human rights violations, which once drove him to contemplate suicide.

Sophie believes the situation in the CIC is exactly what thousands of exiled activists are now facing: indifference, cruelty and alienation. She appealed to Hongkongers who are still able to stay to fight for democracy to amplify detainees’ demands to overhaul the immigration system, “Supporting their struggle is also to fight for our own rights.”