Original: 【「非新聞」創辦人出獄:記錄中國底層抗爭,抵抗強迫遺忘】, published in Squatting 蹲點

Translator: Caeiro

This article has been edited for clarity and precision. If you would like to be involved in our translation work, please get in touch here.

Editor’s note: Everybody has been looking over their shoulder since the sweeping bylaws and articles in Hong Kong’s new national security law were announced just before the 23rd anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover on July 1. Now that Hong Kong and China are confronting the same authoritarian regime, it is perhaps a good time to deepen our understanding of the experiences of activists in mainland China, instead of lapsing into old patterns of complacency in the face of our common struggles.

This article introduces “News Worth Knowing” (非新聞), a citizen journalism outlet archiving civil unrest in China. It chronicles how disseminating information about popular uprisings can be a mode of political mobilization. In unity there is strength.

After four years of imprisonment, Lu Yuyu walked out of prison on June 14. People who still recall his name have likely become few and far between in recent years.

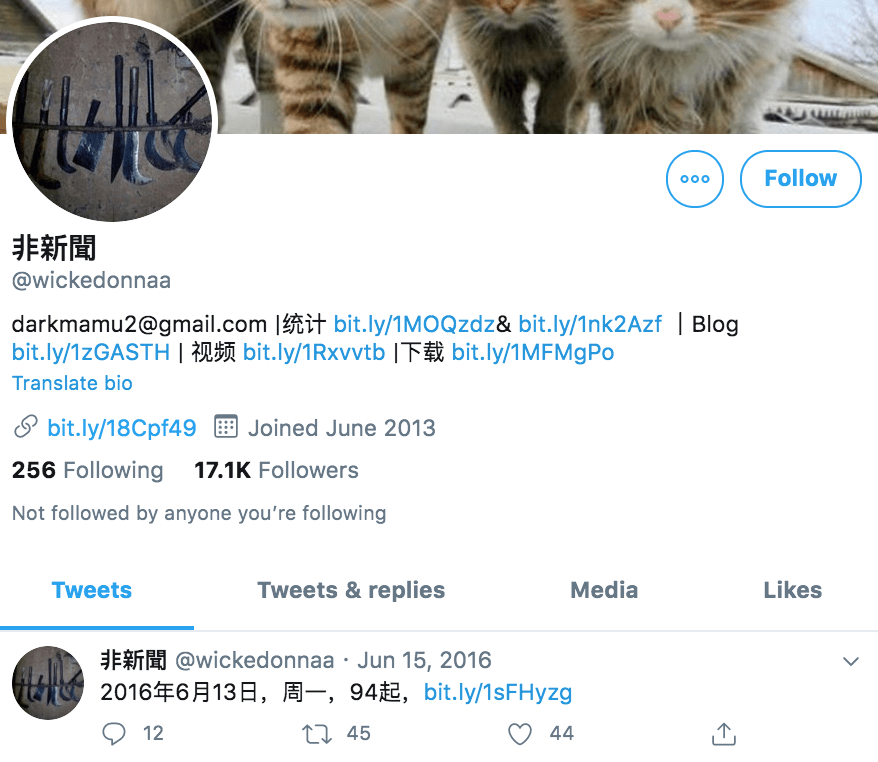

His crime? Managing a social media account called “News Worth Knowing” (非新聞) with his then girlfriend, Li Tingyu, from their home in Yunnan Province. Starting in 2013, they began to meticulously record grassroots uprisings in China. From labor strikes to protests against landlords, “News Worth Knowing” verified the details of these events by cross-referencing multiple online sources.

Lu and Li archived daily acts of resistance otherwise destined to be forgotten, systematically analyzing these actions on a monthly and yearly basis. This information seemed innocuous enough, yet it led to their arrests in 2016. One year later, Lu was sentenced to four years in prison for the offense of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”, and Li was on probation until her release in 2017.

The “News Worth Knowing” Twitter account ceased activity on June 15, 2016—the last time it was updated before Lu and Li were arrested.

Just as China has become “the world’s factory”, it has also risen as a global epicenter of working-class uprisings. Over the past twenty years, there have been so many of these incidents that the government, and even academics, have stopped gathering statistics about them. The responsibility to record these protests then fell on young people like Lu and Li. The social contradictions brought about by capitalism in China has manifested in a rapid increase in rural land disputes, labor movements, and urban resistance against government power.

The last monthly count from “News Worth Knowing” recorded 2,001 demonstrations as of April 2016, including one incident involving more than 10,000 people, 236 incidents resulting in police crackdowns, and at least 2,782 arrests. In its last annual summary from 2015, “News Worth Knowing” recorded 28,950 marches, demonstrations, rallies and other incidents, averaging 79 a day—a 34% increase from 2014. The most common demonstrations came from workers, with over 100,000 such incidents happening in one year. The majority of these incidents were led by construction workers, followed by protests by workers in the manufacturing, processing and service industries.

Just as China is becoming ‘the world’s factory’, it is also becoming a global epicenter of working-class uprisings.

The primary catalyst for demonstrations was unpaid wages. Apart from landowners and farmers, people across various sectors—from investment bankers, to students, to business owners, to students, to parents—have participated in hundreds of thousands of protests in recent years.

The data that “News Worth Knowing” collected represented only a fraction of the daily uprisings happening across China. And yet it had a significant impact on the outside world. For one thing, Lu’s and Li’s archive was one of the primary data sources used by China Labor Bulletin, a Hong-Kong-based NGO, to collate its map of labor strikes in China. For many years, it was widely seen as reliable evidence of a burgeoning mainland Chinese workers’ movement, having been cited by numerous mainstream, international media outlets.

Looking back, Lu’s and Li’s arrests were certainly an example of the repression faced by workers, feminists, lawyers, and anti-discrimination activists since 2015. And yet the severity of their punishments seemed to exceed those suffered by the vast majority of human rights activists arrested during the same period. Why?

In his introduction to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Marx wrote: “Material force must be overthrown by material force; but theory also becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses.” Yet when it comes to galvanizing the masses, the force of history and the power of those who have struggled before us have to be accessed not only through theory but also the archive. To understand and live in the aftermath of this history are fundamental to building stronger theories and practices of resistance: we can only stand to gain from comparing and borrowing from the experiences and strategies of past struggles. This is also how some resistance movements, such as labor strikes, become contagious—spreading from one group to another, from our immediate communities to those far away. “News Worth Knowing” opened up many radical possibilities through a dissident archival practice, and may have been especially provocative as an activist project for this reason.

Government repression in China does not simply set out to stifle action, but also to block information, obstruct the spread of ideas, and maintain a false image of society’s stability. Compared to those with more public profiles or those who are more active in social movements, Lu Yuyu’s and Li Tingyu’s names may not be very well-known. But we must remember them, not only because of their patient collation of this data, day in, day out; but because we should remember the countless, anonymous protesters who have participated in grassroots movements throughout the years. To honor past struggles is to also remember, to refuse to forget.