Domestic workers perform the invisible but essential labor that keeps the world running while experiencing structural exploitation and precarity. From the frontlines of COVID-19 to the vicissitudes of daily life in the racialized and gendered international division of labor, domestic workers have been systematically devalued, neglected and abused with little to no recourse to collective power and legal protection. Amplifying the voices of care workers, migrant workers and labor organizers in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia have been central to critiquing the devastation of capital across multiple empires. On this International Domestic Workers Day, we look back on a range of translated and original perspectives we have published on the global struggle of domestic work:

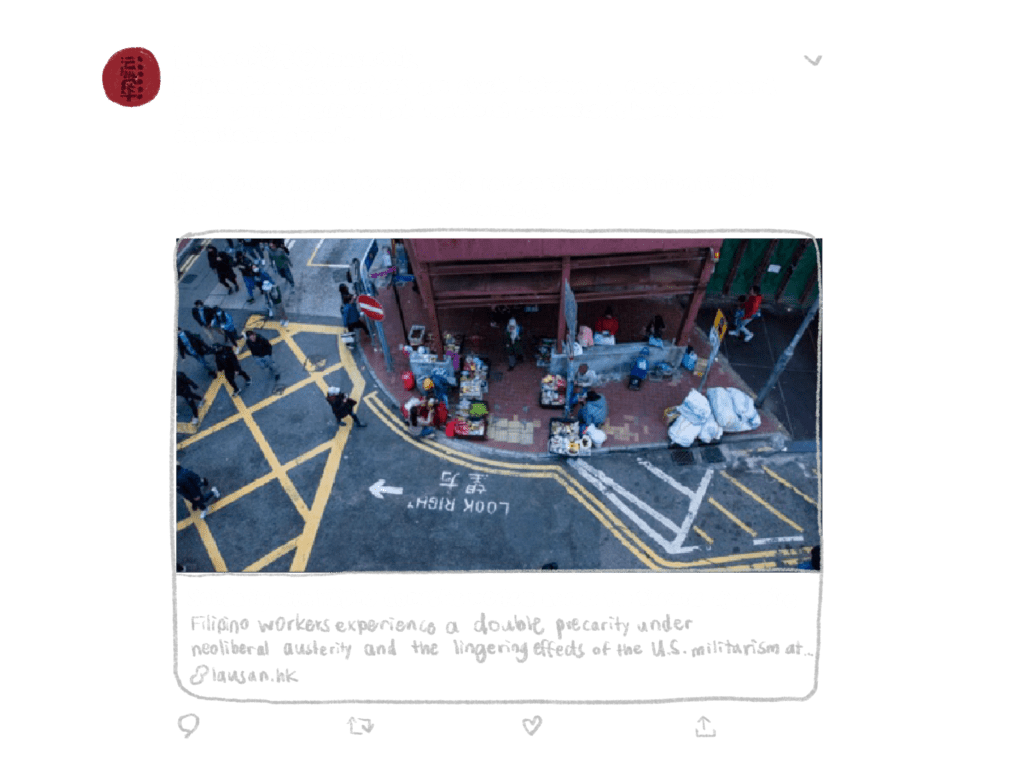

1. Solidarity with Filipino domestic workers across the fissures of empire

Filipino migrant domestic workers are caught between a rock and a hard place. They experience a double precarity: at home, they encounter the disastrous effects of neoliberal extraction, corrupt elections, and U.S. military empire; abroad, they endure alienation and abuse as “cheap export labor” from negligent governments and predatory agencies.

Hong Kong needs to take a closer look at its ties with U.S. elites and its role in the dispossession of Filipino workers. It is time for the movement to leverage its international position to fight for the rights of migrant workers. Shiela Tebia, Chairperson of Gabriela Hong Kong, shares her experience in organizing migrant workers to combat exploitation and raise awareness of the political situation in the Philippines:

2. Care workers in the epidemic—Foreword

Just as the public health crisis intensifies, the invisible labor of care risks further erasure. The coronavirus outbreak in Hong Kong lays bare many of the underlying issues already plaguing our society. One of those is the general depreciation of care work, which has left domestic workers to take on a lot more work and stress as the public health crisis intensifies.

Our friends at Grass Media Action 草根.行動.媒體 spoke to carers about their experiences and working conditions throughout the ongoing pandemic, hoping to bring awareness to the deprivation and discrimination that care workers face while shedding light on possibilities of resistance and transformation.

3. Care workers in the epidemic—Part 1: Care work, employment and race

Migrant workers live and work under increasingly unforgiving conditions. But while current circumstances of pandemic may see reproductive labor face further erasure, this moment also enables us to better understand how care work has been relegated to the bottom rung of our social priority; we cannot afford to overlook its effects on mothers, housewives, and migrant domestic workers who have long been shouldering this collective responsibility.

4. Care workers in the epidemic—Part 2: Twenty years as a migrant worker mother

Two pandemics, four employers, two decades of fierce commitment to organizing migrant workers in Hong Kong: The pandemic has not slowed the momentum of community organizing for Filipino migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong. For longtime union organizer “Nanay” (Tagalog for mother) Nida, fighting for the rights of fellow workers while keeping a close eye on the Philippine government has only become more pressing.

5. Care workers in the epidemic—Part 3: Caring for children with special needs

The suspension of classes in the pandemic has compounded the arduous yet overlooked labor of many care workers in Hong Kong. Over 40% of women interviewed in one study have stopped working in waged positions to care for their families. Meanwhile, migrant domestic workers continue to experience predatory hiring practices and toil under exploitative living and working conditions. A mother of two children with special needs explains her daily challenges in the current crisis, and discuss how we can connect the struggles of people with different abilities and migrant domestic workers.

6. ‘Whether you call us Hongkongers or not—we are part of Hong Kong’

“What happened in Hong Kong inspired Indonesians and gave them motivation. But the movement in Hong Kong was also inspired by previous movements in Indonesia. We support their movement because we feel that we are a part of this community even if not all of their demands include us. We extend solidarity because we know that if Hongkongers lose their freedom of expression, so will we.”

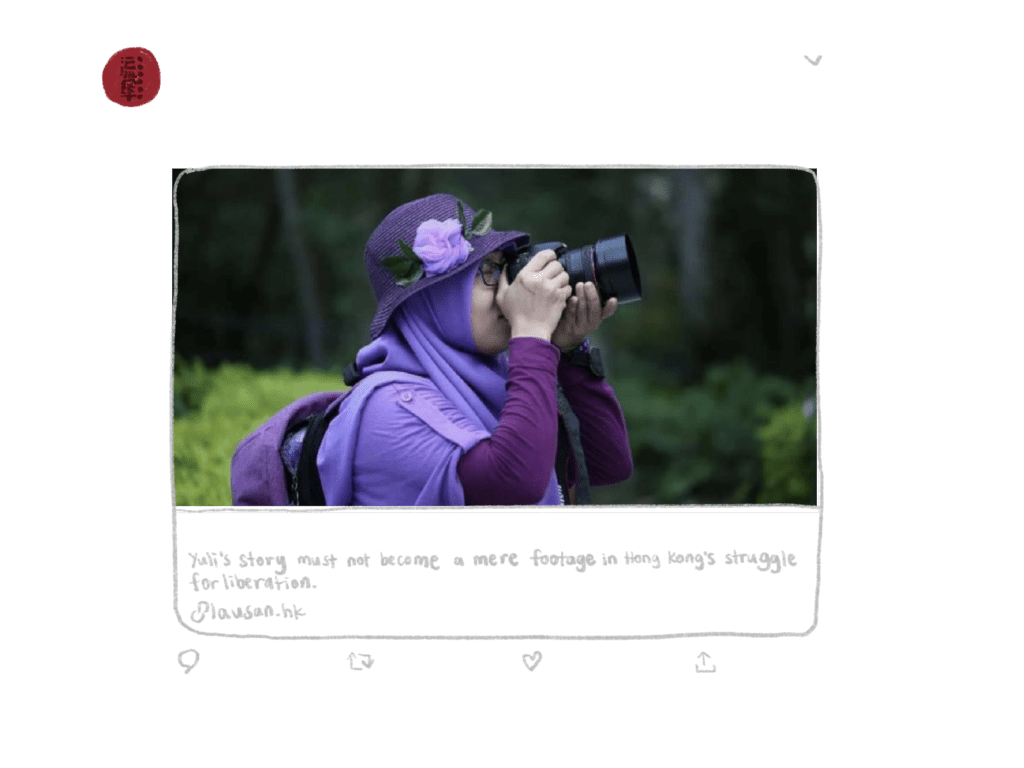

Read Indonesian migrant worker, writer and journalist Yuli Riswati’s reflection on invisible forms of participation in the movement and shared struggles between Hong Kong and Indonesia.

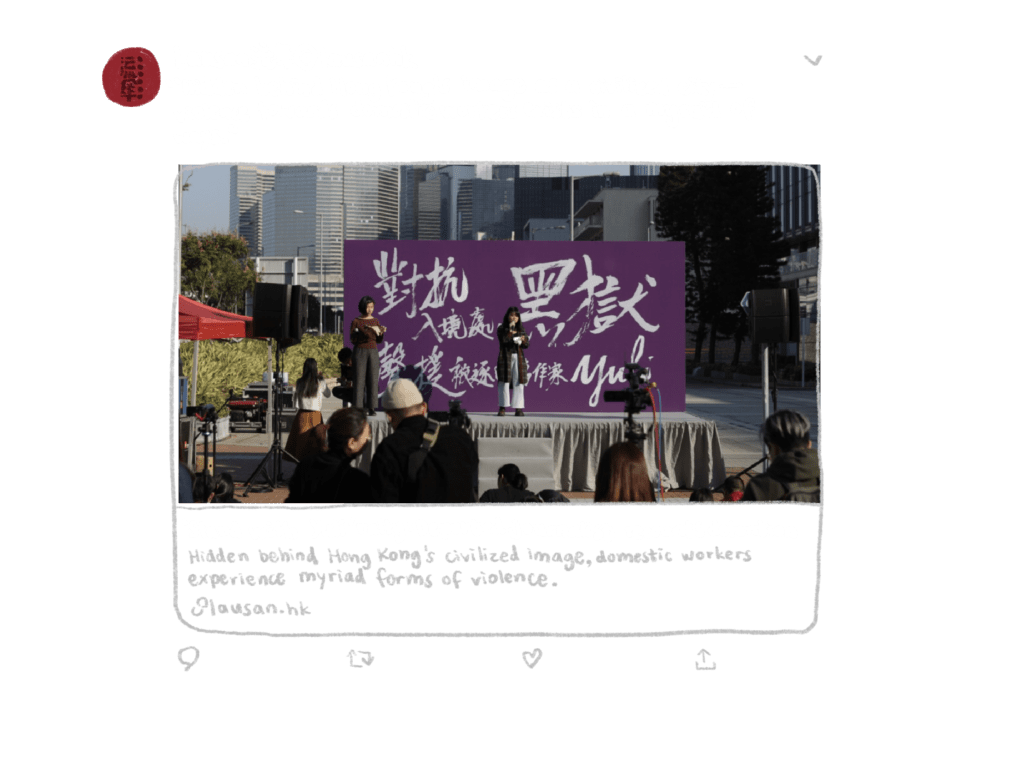

7. ‘Stand with Yuli’ rally: Deported journalist recounts detention

Hidden behind Hong Kong’s civilized image, domestic workers experience myriad forms of violence. Yuli Riswati calls for solidarity with all facing incarceration and deportation, “If you really want to help, please do not only help me, but help everyone in immigration detention.”

8. Hong Kong deports writer and migrant worker Yuli Riswati

Hong Kong immigration authorities deported award-winning Indonesian writer and migrant domestic worker Yuli Riswati, who played a vital role in documenting this year’s protests. The detention and deportation of Yuli—as well as the inhumane treatment she has faced inside Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre—is not an isolated injustice. Her deportation is no doubt politically motivated, and all Hongkongers must take notice. Her story must not become a mere footnote in Hong Kong’s struggle for liberation.

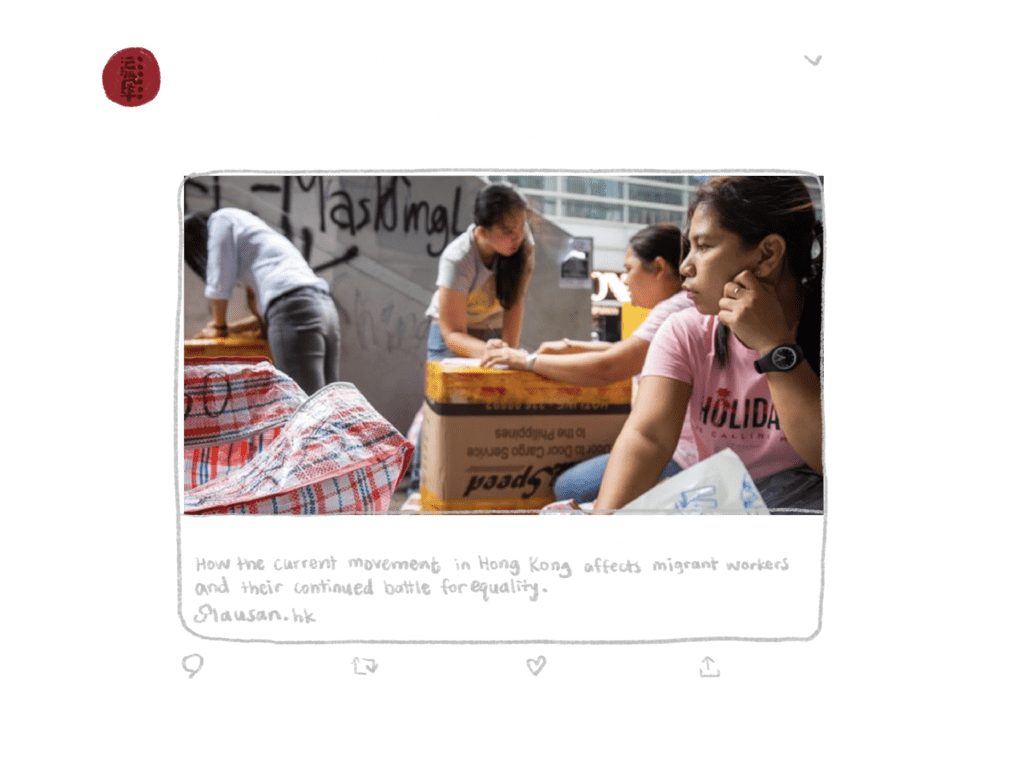

9. Domestic workers search for rights amid Hong Kong’s protests

Some migrant community leaders and critics of the pro-democracy movement have voiced concerns that the protests ignore or overshadow the demands of workers, such as freedom of assembly, the right to a living wage and suitable living conditions. Nevertheless, migrant worker community groups frequently organize their own rallies relating to these issues, and have a history of participating in social movements in Hong Kong; they supported striking dock workers in 2013 and the anti-World Trade Organization protests in 2005.

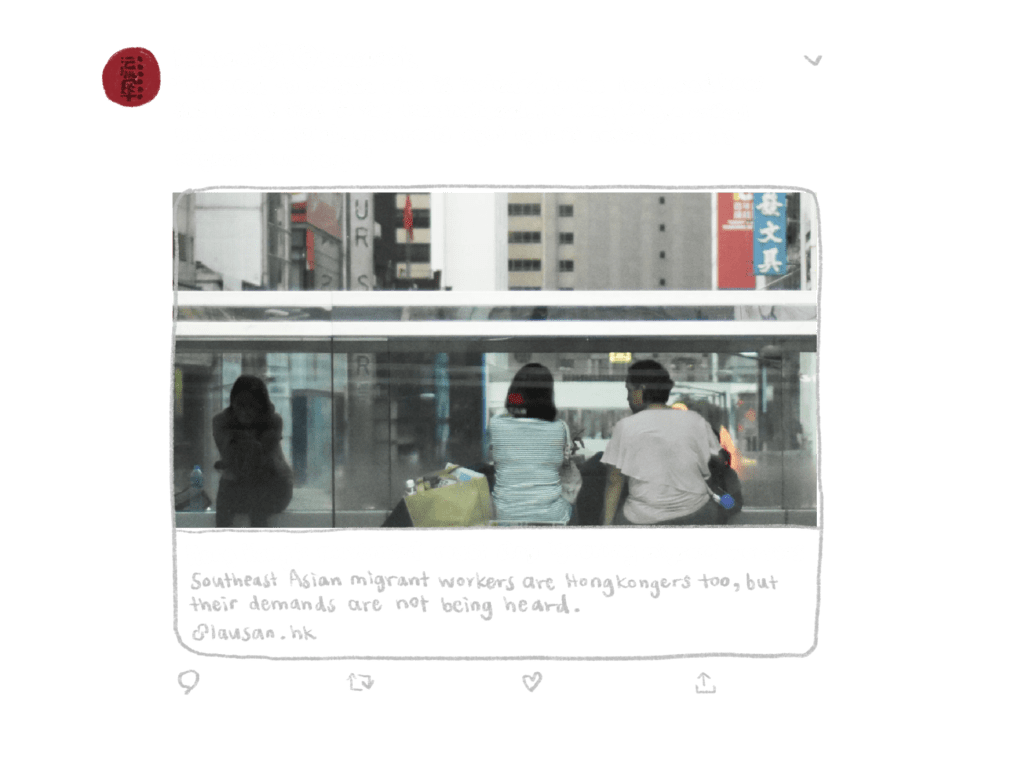

10. Hong Kong’s movement must stop ignoring migrant workers

Who is included in the “自己” (myself) of the protestors’ chant: “自己香港自己救” (We alone will save our own Hong Kong)? To combat the CCP’s authoritarian capitalism, Han-centric imperialism, and exclusionary ideologies such as Hong Kong ethnonationalism, we must look inward: freedom lies not only in the vanguard in the black masks, but also in the many who are absent from the front lines. We need to rethink who is included in the local, and how the local is tied to the transnational. For Hong Kong, a critical link to the global, grassroots fight against capital, are its migrant workers.

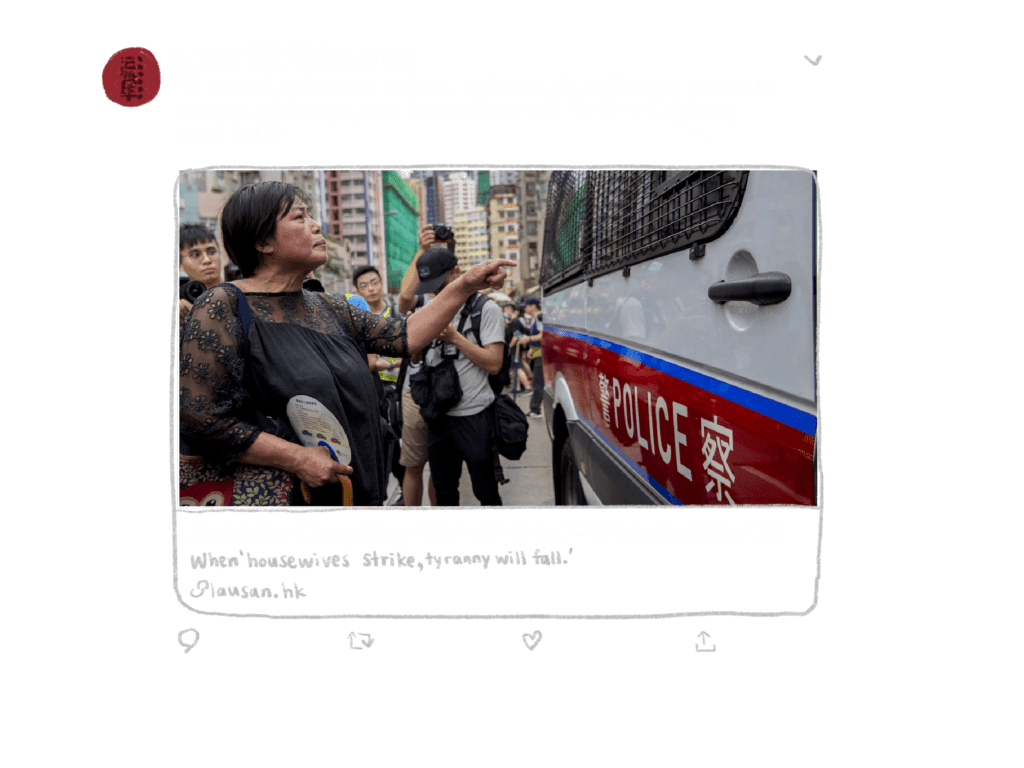

11. Joint letter: Hong Kong housewives against the extradition bill

Kwun Tong–based housewife Wong Choi-fung questions how the rights and conditions of housewives are negatively impacted under “One Country, Two Systems,” and calls for transnational solidarity between housewives, especially those facing political and economic oppression in China. Female laborers are not ephemeral to Hong Kong and Chinese workers’ struggle for liberation.