Read the Chinese version here.

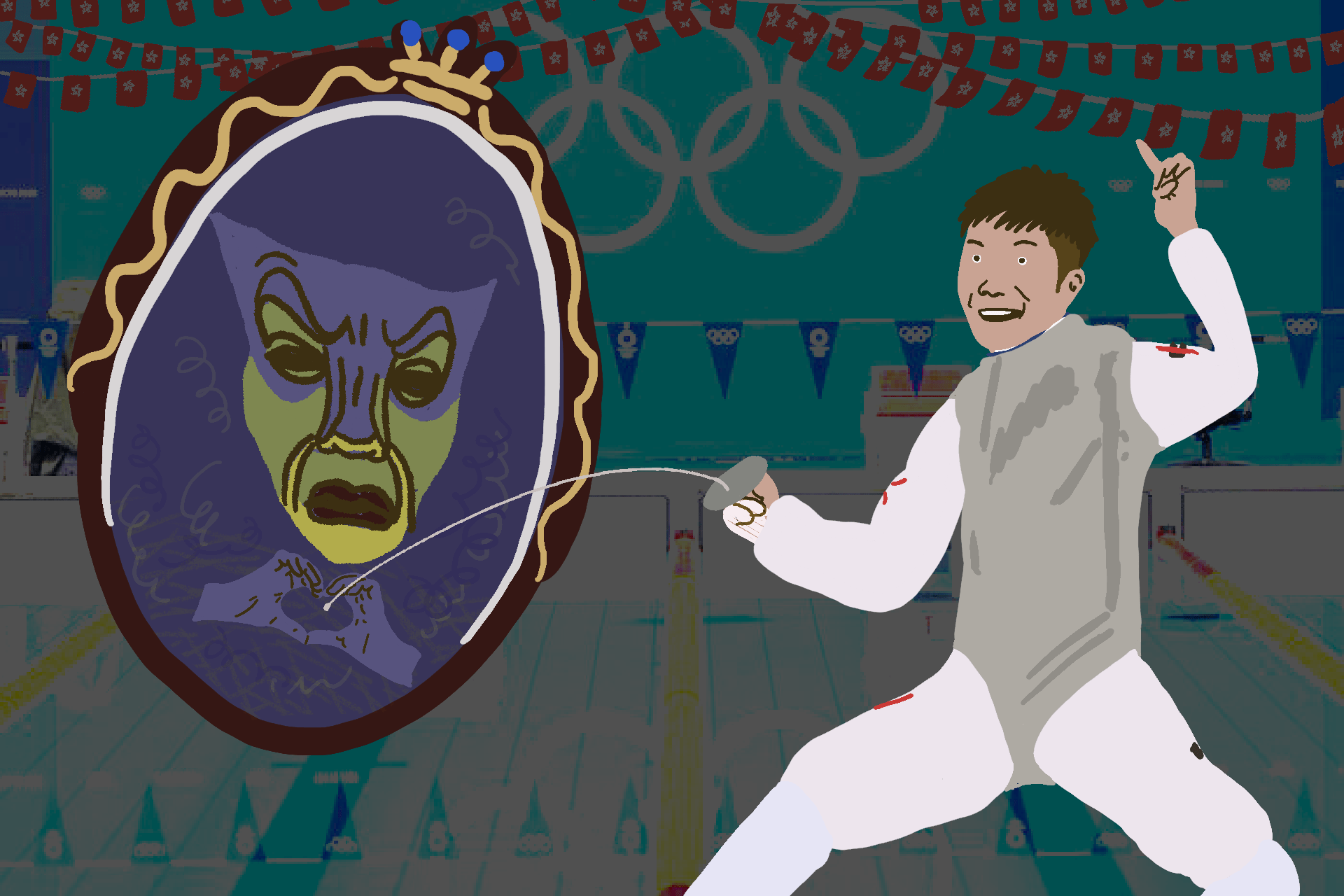

While Hong Kong’s Edgar Cheung Ka-long was competing in the men’s foil final at the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo, spectators gathered at the APM mall in Kwun Tong district, where the match was being televised, to chant slogans of “Hong Kong Add Oil” and “We are Hong Kong.” When Cheung won his match, fans booed the Chinese national anthem. The mood of the spectators that night was strikingly similar to the crowds that had gathered at Hong Kong’s shopping malls throughout 2019 for “Eat with You” and “Sing with You” rallies, where they chanted pro-democracy slogans, sung protest anthems, and displayed banners, artwork, placards, and other protest paraphernalia. Someone in the crowd even unfurled a British Hong Kong flag—a contentious symbol of defiance against the Chinese Communist Party and their rule. Four days later, the Hong Kong police announced that they had arrested the person who had displayed the British Hong Kong flag. They alleged that he had instigated the booing, and charged him with insulting the Chinese national anthem, making him the first person to be charged under the new National Anthem Ordinance.

The spectre of the National Security Law (NSL) also loomed over the mall spectators. The trial of pro-democracy protestor Tong Ying-kit, which ran concurrently with the Olympic festivities, resulted in the 24-year-old’s conviction the day after Cheung’s victory. The verdict against Tong, the first person convicted under the NSL, hinged on the key issue of whether his display of the “Restore Hong Kong” slogan would alone be capable of inciting secession. The three-judge panel handpicked by Chief Executive Carrie Lam held that it was. This ruling and a cascading number of arrests under the NSL have repressed not only public discussion of political issues and direct participation in political activity and organisation, but now even cultural expressions such as the fan reaction to Cheung’s victory.

In the face of this draconian suppression of dissent, nominally “apolitical” celebrations of Hong Kong’s Olympic triumphs, such as swimmer Siobhan Haughey’s two silver medals, have become expressions of Hongkongers’ shared identity. By extension, they have also become a celebration of Hong Kong’s unique language, society, and culture in defiance of Beijing’s authoritarian and totalising one-country rhetoric. With the quashing of even the most benign forms of political organising, including students’ and employees’ unions and civil society groups, we can see that collective public interest in local sports, and the sense of community forged through it, have now become a covert haven for the spirit of resistance born in 2019 that may help to weather the storm of political repression.

These recent incidents are not the first time that sporting events in Hong Kong have taken on a politically charged character. As far back as 2017, there have been incidents of Hong Kong football fans booing the Chinese national anthem and chanting “We are Hong Kong.” During the height of the 2019 protests, a hockey match between youth teams from Hong Kong and neighbouring Shenzhen, with Hong Kong leading 11-2, devolved into a brawl after members from the Shenzhen team began attacking their Hong Kong rivals. The ardent localism of Hong Kong football fans prior to the 2019 protest movement can be attributed to the common role of football clubs and teams as representatives of a local collective identity.1 However, it is certain that the uprising of 2019 and the subsequent shrinkage of space for political discourse in the face of government repression has bestowed upon sports a heightened political dimension. In particular, sports fandom has often acted as a relatively more acceptable venue for those who have had their local identities challenged or suppressed to assert their pride in a form of “national” identity.

In the early 20th century, sports was often used by the ruling class and capitalists to pre-empt worker dissatisfaction, where sporting facilities and events were provided as concessions to organized labor, or as a cultivator of chauvinism and subordination to authority, as Noam Chomsky has argued.2 The global nature of the Olympics, on the other hand, have long made the Games an occasion for fierce nationalistic competition. Great powers battle it out for the highest sporting accolades, with China now taking the place of the Soviet Union as the United State’s foremost contender for dominance over the medal table. Despite this, international games have also been an opportunity for colonised people or those with tense relationships to a dominating power to assert their identity and pride on the world stage. In the case of Hong Kong and Taiwan, direct competition with athletes representing the People’s Republic of China have sometimes become tense when nationalist expressions arise.

In the case of Hong Kong and Taiwan, direct competition with athletes representing the People’s Republic of China have sometimes become tense when nationalist expressions arise.

For example, the informal treatment by International Olympic Committee (IOC) officials and workers of athletes from Finland (then a part of the Russian Empire) as representatives of a separate country during the 1912 Games was a “decisive boost” to the Finnish independence movement. At the same time, the IOC, in their pursuit of making the games an “apolitical” affair, has historically suppressed opportunities for political expression that run counter to the interests of its most prominent participant countries to manifest. In 1912, the IOC kowtowed to imperial interests by barring athletes from Bohemia, then a part of Austria-Hungary, from participating as a sovereign nation. More recently, this year it banned social media teams from posting pictures of athletes taking a knee to protest anti-Black racism. Even so, such institutional attempts to depoliticize the Games can be subverted. The Chinese national anthem was the soundtrack to Hong Kong’s Olympic victories, yet the global recognition of such triumphs as distinctly “Hongkonger” in nature, especially after the widely covered 2019 protests, has already served as powerful symbolic affirmations of the uniqueness of Hong Kong’s local cultural identity.

These affirmations of a local culture may be short-lived, but they are nevertheless important. We can draw a parallel here with the Czechoslovakia Hockey Riots of 1969. Czechoslovakian hockey fans had already put their anti-Soviet sentiments on display during the 1959 world tournament, cheering for the Soviet team’s American opponents.3 Following Czechoslovakia’s victory over the Soviet team in the 1969 World Ice Hockey Championships, half a million Czechoslovakian fans took to the streets to celebrate. Coming right after the short-lived Prague Spring—attempted liberal and democratic reforms by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which resulted in the invasion by the Warsaw Pact—the euphoria of Czechoslovakia’s victory turned into mass protests against the Soviet military occupation. Fans cheered and chanted “No tanks were there so they lost!” and “Czechoslovakia 4—Occupation forces 3!”

Despite the protests, Czechoslovakia would return to authoritarian one-party rule, which would last for the next two decades. The anti-Soviet chauvinism and nationalism of the Czechoslovakian hockey fans gives credence to George Orwell’s remark that sports was “war minus the shooting,” but also shows that sports can allow for demonstrations of political sentiment in circumstances where “politics often encouraged people to conceal their true feelings.” Under the NSL, Hongkongers might not be able to get away with overt political dissent, but fanclubs that celebrate symbols of Hong Kong’s unique culture—be it sports, pop stars, music groups, or even the city’s distinctive double-decker buses—remain venues for people to come together and get organized on the basis of a shared identity. Such bonds will be crucial in political struggles to come.

In the current political climate, pervaded by fear of the opaque and arbitrary NSL now being used to target pro-democracy organizations and individuals, it seems unlikely that Hong Kong athletes will be able to be outspoken advocates for Hong Kong’s struggle. Government officials have already begun to send that message: A pro-Beijing politician condemned a Hong Kong badminton player at the Olympics simply for wearing an unmarked black sports jersey, since the color became associated with protesters in 2019.

Under the NSL, Hong Kong athletes could jeopardise more than just their sporting careers if they made powerful political statements like African-American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who raised the Black Power salute on the podium at the 1968 Olympics to protest against anti-Black violence in the US. It also seems unlikely that local footballers will follow in the footsteps of Algerian Rachid Mekhloufi—one of France’s topmost football strikers, who, during the height of Algeria’s War of Independence, had defected from France to play instead for the team of the National Liberation Front. Most recently, the case of Krystsina Tsimanouskaya, the Belarusian sprinter who criticised the decisions of her country’s sports officials at the Tokyo Olympics, illustrates the danger to athletes who offer even the mildest criticism of authoritarian regimes: She was threatened with repatriation and reprisals by the government and members of the national Olympics team (headed by President Alexander Lukashenko’s son) and has now received asylum in Poland. Tsimanouskaya’s situation shows that to rely on celebrity athletes’ opposition to authoritarian regimes is a form of struggle that is neither reasonable nor sustainable. We also cannot rely on the Olympics as a forum for protest alone since it is itself an agent of the same unaccountable governance and cronyism that Hongkongers are fighting against: The Games and IOC have long been criticized for corruption, as well as enabling gentrification and the militarization of police to clear homeless populations in Olympic cities around the world.

In an era where the Hongkonger identity is under attack and where there are scant opportunities for overt acts of collective resistance against the regime, the binding force of these cultural expressions shouldn’t be overlooked.

Rather, it seems that Hongkongers’ celebration of their sporting triumphs will take on a character akin to the popularity of the locally produced hit TV drama Ossan’s Love (the target of homophobic attacks by a pro-Beijing politician for its depiction of same-sex romance) or their love for MIRROR, the highly successful Cantopop boy music group. Neither are explicitly political icons; indeed, as conventional forms of entertainment that rely on government-regulated broadcasting networks, they cannot afford to be. Still, as pop culture icons made in and inextricably of Hong Kong, they stand as symbols for self-identification with the Hong Kong community and its values, idiosyncrasies, and colloquialisms. In an era where the Hongkonger identity is under attack and where there are scant opportunities for overt acts of collective resistance against the regime, the binding force of these cultural expressions should not be overlooked. As pro-democracy labour unions, civil society organisations, and media outlets have all now been targeted by the police, the judiciary, government officials, and pro-Beijing politicians, many have voluntarily disbanded out of concern for the safety of their members, leaving few traditional methods of collective resistance available.

It would be easy to mistake this period of abeyance in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy struggle as a total defeat and loss of political energy, especially compared to 2019 and 2020. But it may be more productive to think about the present as a moment to rest, regroup, and find joy in community, acts that build the networks of care and solidarity that are critical to political struggle everywhere. Like those on the mainland, who have many years of experience creatively evading censorship and repression by the Chinese Communist Party, Hongkongers’ expressions of local identity as a form of implicit resistance to “mainlandisation” (real and perceived) are now a fluid and ever-moving target. Instances of solidarity like sports fandom can be ephemeral when viewed from the outside, taking on new forms as soon as they are repressed, but they are no less powerful in the internal work of rebuilding community.

Most likely, the strong bonds of anti-authoritarian sentiment and solidarity with fellow Hongkongers that were forged in the uprising of 2019 will survive—dormant but persistent—through collective engagement and celebration of a shared local identity, whether in sports, TV shows or beyond.

Footnotes

- Tony Collins. “The Second Revolution: Sport Between the World Wars.” Sport in a Capitalist Society: A Short History, Routledge, 2013.

- Noam Chomsky, “Spectator Sports.” Understanding Power, eds. Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel. The New Press, 2002.

- Oldrich Tuma, Mikhail Prozumenschikov, John Soares, and Mark Kramer. “Complexity in Soviet-Czechoslovak Hockey Relations.” The (Inter-Communist) Cold War on Ice: Soviet-Czechoslovak Ice Hockey Politics, 1967-1969, ed. James Hershberg. Cold War International History Project. Wilson Center. 2014.