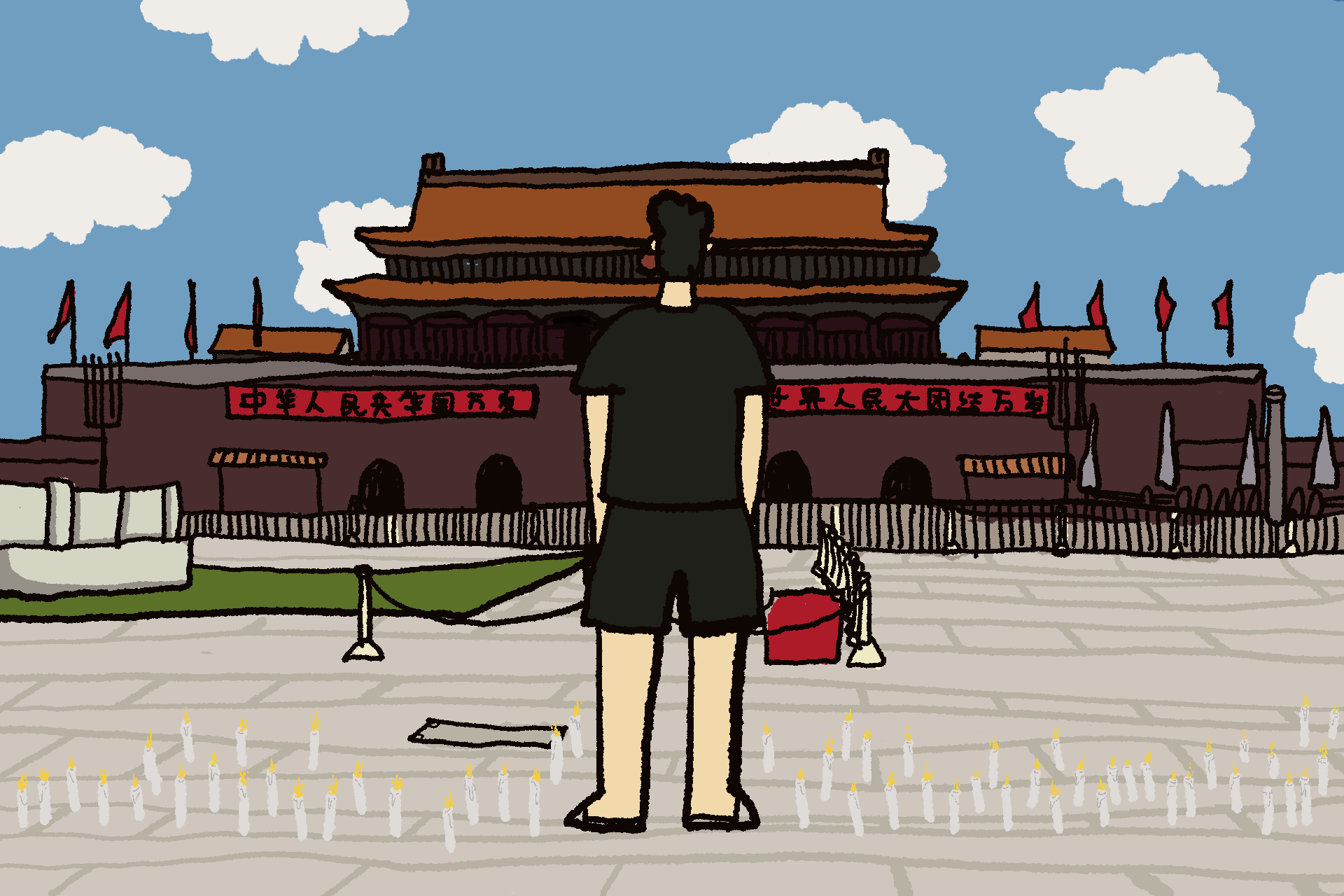

Editor’s note: In recent years, Hongkongers across the political spectrum have debated the relevance of Tiananmen and the June 4 vigil to Hong Kong’s new era of struggle. These discussions shift frequently due to the unpredictable and escalating nature of repression by the Hong Kong government: This year’s vigil has been banned for the second year in a row, and is being accompanied by heavy police surveillance of traditional and non-traditional public spaces of commemoration.

As the Hongkonger identity continues to evolve, influential youth political groups have questioned the purpose of the June 4th vigil in Victoria Park in particular. While most student groups recognize the historical importance of Tiananmen and continue to commemorate the massacre through discussions and educational panels, they have simultaneously argued against linking Hong Kong’s struggle for democracy with the struggle in mainland China. For many who were bothered by the pseudo-patriotic elements of past vigils, the government’s repression has given new political meaning to the act of public commemoration itself. Moreover, there are signs even amongst staunch localists that moments of shared struggle (such as the courageous work of mainland human rights lawyers who helped 12 detained Hongkongers in China) can invest the June 4 vigil with renewed potential for cross-border solidarity and understanding.

To contextualize these many changes, we look back to the history of Hongkongers’ long-standing support for the democracy movement in mainland China. Lausan spoke with Hong Kong leftist Lam Chi Leung, who has been a participant and critical observer of the vigil since the early 1990s. He argues from a leftist perspective that June 4 still has enduring relevance for Hongkongers fighting for democracy—but only if it once again becomes a vehicle for cross-border solidarity and for connecting our separate but increasingly similar struggles for democratic self-governance under CCP repression. It should be noted that while Lam argues for a unified struggle for democracy in “the whole of China including Hong Kong,” which reflects current legal-political realities of Hong Kong as a so-called “special administrative region” of China, this does not imply any endorsement of a state-centered “One China” policy.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Lausan Collective: Who are the individuals and groups in Hong Kong that organized support for the protesters during the pro-democracy movement in 1989, and how did the annual commemoration in Hong Kong come about?

Lam Chi Leung: When we talk about Hong Kong’s support for the democracy movement in China, we generally think of the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China (hereafter, Alliance). The coalition was founded on May 21, 1989, mainly by the secretariat of the Joint Committee for the Promotion of Democratic Government. At the time of its founding, it had 225 member groups, including Members’ offices, district groups, student unions, trade unions such as teachers, social workers and civil servants, and left-wing groups. But the general composition was made up of middle class professionals with the leadership being mostly moderate democrats. It should be stated up front that Alliance was instrumental in helping survivors of the violence at Tiananmen Square escape to safety in Hong Kong, for which they deserve a lot of credit.

Left-wing groups, labor organizers, and women’s movements were the earliest supporters of the pro-democracy movement in China. A united front in support of China’s democratization called April Fifth Action (AFA), also formed in early 1989. It included individual members and groups such as October Review, the Pioneer Group, and the Revolutionary Marxist League. Many were members of the Alliance as well but their relationships with the Alliance leadership were characterized by both cooperation and conflict, sometimes culminating in intense confrontations but never complete ruptures. But, fundamentally, the moderate democrats were hostile toward the leftists in the Alliance.

In May 1989, shortly before the formation of Alliance, a group of students and pro-democracy activists including journalists, academics, and NGO workers went to Beijing to visit the protesters and bring them donations raised by the Hong Kong public. At the same time, a diverse group of leftists also went to Beijing and elsewhere on the mainland. I was in Guangzhou for the entire pro-democracy movement up to the crackdown. I remember at the end of May, a number of friends from Hong Kong, from labor and women’s groups, arrived in Guangzhou. Together we attended a meeting jointly organized by students from several universities in Guangzhou.

Between May and June, there were several marches and rallies in Hong Kong, each with a massive turnout. In 1990, it seemed logical to start the first candlelight vigil in Victoria Park. At that time, there were two events: a march would be organized on the weekend before the June 4 anniversary, and a vigil would take place in Victoria Park on the night of June 4. The march on the first anniversary of June 4 in 1990 was attended by more than 300,000 people and the vigil by 150,000 people. This tradition has continued ever since.

LC: It has been more than 30 years since the first vigil in Hong Kong. How has the event and its meaning changed over those three decades?

LCL: There are four periods: 1989-1997, 1997-2003, 2003-2013, and 2013 to the present.

From 1989 to 1997, the solidarity movement in Hong Kong was large. Many Hong Kong people would commemorate June 4 with a sense of sadness. The increased political awakening of Hong Kong people was based, to some extent, on their identification with the Chinese democracy movement and their identity as Chinese. It was a common mentality at the time for people to think of themselves as Chinese and that it was one’s ethnic duty to help China move toward democracy. At the same time, many also hoped that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would soon fall so that they wouldn’t live under dictatorship after 1997. It was with a fearful mindset that they participated.

As the Handover approached, many people worried about whether the commemorative events could still be held or not. It turned out that there wasn’t a lot of pressure because, at the time, it was China’s political intention to not rock the boat and to gain international trust, even after the military repression at Tiananmen. Because of this, the number of participants didn’t decrease significantly in the subsequent decades. But momentum can’t be maintained if the movement only positions itself as support from the outside.

Before 1997, through articles and leaflets, those of us in the left-wing Pioneer Group and Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS) factions in the Alliance promoted the idea that Hong Kong was already an integral part of China. We argued that people from both sides of the border should join hands to fight for democracy in both places, which included democratic autonomy for Hong Kong. However, the Alliance leadership, made up mostly of pan-democrats, has for a long time avoided dealing with local Hong Kong affairs in their activities. The leadership viewed Alliance as strictly a vehicle for organizing around solidarity with Tiananmen—these moderate democrats such as Szeto Wah and Albert Ho were involved with local issues through other organizations. There seemed to be an unwritten division: China is China, Hong Kong is Hong Kong, and “well water should not mix with river water.”1 In essence, the Alliance doesn’t consider the mass movement in Hong Kong and mainland China as two sides of one Chinese democratic movement.

Many Hong Kong civil society groups were also not satisfied with this type of compartmentalization. For example, prior to the major split in 2013, when left-wing groups and the HKFS participated in the June 4 vigil, they chanted slogans such as “Democracy in China and Hong Kong is of one family, well water and river water can merge” to show their difference from the leadership of the Alliance. In 2003, when 500,000 people marched against Article 23 of the Basic Law, the attitude of the Alliance changed, and their slogans began to include calls for democracy in Hong Kong revolving around the demand to “abolish Article 23 legislation.” But the Alliance leadership’s fundamental refusal to allow the coalition to engage fully with Hong Kong local affairs didn’t change significantly and it was this rigidity that led to the discontent and rise of far-right localism.

The Alliance leadership’s fundamental refusal to allow the coalition to engage fully with Hong Kong local affairs didn’t change significantly and it was this rigidity that led to the discontent and rise of far-right localism.

In a landmark event, the far-right localists organized their own event in Tsim Sha Tsui in 2014 on June 4, and no longer participated in the Victoria Park gathering. At this event, they argued that we shouldn’t advocate for the vindication of June 4 and the building of a democratic China. They also believed, like Alliance, that Hong Kong is Hong Kong and the mainland is the mainland but they came to this conclusion based on the adamant belief that Hong Kong isn’t responsible for democracy in China. They reasoned that we shouldn’t interfere, and if we do, the mainland will in turn interfere with Hong Kong’s affairs.

This stance caters to the idea of some in Hong Kong that they don’t have the power or responsibility to interfere or change the mainland now. Such a sentiment has only grown. The Alliance never responded forcefully to this idea either, likely because its leadership sees its primary usefulness as offering solidarity rather than a commitment to building democracy in the mainland.

LC: Can you elaborate on some of theses criticisms of Alliance coming from within the coalition and also from outside?

LCL: In the early days, there were criticisms of the leadership’s arbitrary decision-making, such as not allowing the public to speak during the vigil. Since then, there have been changes, such as no longer prohibiting other member groups from chanting slogans, and holding listening sessions before and after the vigil to allow the general public to express their opinions. However, the Alliance leadership still insists on disallowing the views of the member groups in the Alliance to be expressed on stage during the vigil, an attempt to have the coalition always speak with one voice.

The Alliance has also long used a strong nationalist and “Greater China” identity and rhetoric mobilize public participation. But I believe Hong Kong people should support democracy in China not only because of any sort of ethnic or nationalist identification with “Chineseness,” but for deeper and more practical reasons too. The Alliance has traditionally been unwilling to entertain such discussions, which explains the splintering of young people such as the HKFS and the radicals organizing their own marches.

In the past decade, the more radical democratic and left-wing activists would also launch their own march after the vigil from Victoria Park to the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in Sheung Wan, to express their demands directly to the representatives of the regime.

LC: You point out that it’s problematic to use ethno-national identity as the basis for solidarity with the pro-democracy movement on the mainland. Many Hongkongers increasingly don’t identify with being Chinese, but have come to different conclusions about what to do about that. Can you comment on this?

LCL: The new generation of young people care more about if democracy will prevail in China, not so much their own Chinese identity. In 2013, the Alliance originally set the theme of “Love for the Nation, Love for the People, the Spirit of Hong Kong,” but was later criticized by the public and the founder of the Tiananmen Mothers group, Ding Zilin. The Alliance later decided to withdraw the slogan. Around the same time, more people stopped participating in Alliance events and joined the activities of the far-right localists who were developing their Hong Kong nationalist stances.

Because of Alliance’s hesitancy to engage in local affairs and mainstream democrats failure to provide a new progressive narrative, far-right localists were able to exploit this gap and rapidly expand their reach. A new progressive narrative should include a unity between people in Hong Kong and the mainland to fight for democracy, recognizing Hong Kong’s autonomy, opposition to both Han Chauvinism and Hong Kong nationalism, and support for workers and all oppressed groups.

In 2014, after the Umbrella Movement, university students started a campaign to withdraw from the HKFS, accusing it of not representing university students and acting too conservatively during the Umbrella Movement. The remaining members of HKFS decided not to participate in the June 4 commemoration thereafter.2 This was the result of far-right localists seizing the reigns of HKFS, which had been formerly progressive, and turning against the democrats and the leftists. If we oppose the undemocratic “big platform” of the Alliance, we should use democratic methods to fight for change or even replace the leadership, instead of advocating simply to “tear down a big platform” and all democratic processes with it.

We should use democratic methods to fight for change or even replace the leadership of Alliance, instead of advocating simply to “tear down a big platform” and all democratic processes with it.

LC: On that note, when we hear expressions of solidarity with the pro-democracy movement in mainland China, it’s not always clear what kind of democracy is being envisioned. How should we understand the different versions of democracy at play?

LCL: At the time, the moderate democrats who led the Alliance didn’t oppose the restoration of capitalism in China, but only argued that economic reforms should be accompanied by political reforms against corruption. Szeto Wah’s Democratic Party believes in neoliberalism and small government, and in the first decade of the party’s existence, resisted supporting minimum wage legislation throughout the 1990s.

On the other hand, in the immediate post-1989 moment, left-wing groups within the Alliance expressed their support for mainland SOE workers who were fighting against privatization. We didn’t get into heated arguments with the Alliance leadership at this time but we definitely imagine democracy in different ways. The mainstream democrats in Hong Kong, such as the Democratic Party, want China to establish Western-style, liberal parliamentary democracy, while we fight for simultaneous democratization of the economy and politics, and for workers’ democracy.

LC: This is the second year in a row that the vigil has been banned by police, who have used the pandemic as pretext. With the added pressure of the National Security Law, what do you think will happen next?

LCL: The increasing pressure over the past two years makes us all uncertain whether the vigils will continue in the future or even be permanently banned. It may not take long to happen. It also depends on the political climate in mainland China. It’s likely that the five major policy platforms of the Alliance, especially “ending one-party dictatorship and building a democratic China,” will be targeted.

Now, even though the changes in Hong Kong are intense, there is still a certain degree of freedom of publishing and expression, though we don’t know when it will be further tightened nor when some topics will become “sensitive.” We should make use of these freedoms while we can to express our principled positions, and to take stock of the past movement while looking forward to the future.

There are questions that urgently need to be discussed, such as whether China has now become a regional hegemon, even if people disagree on whether it is already imperialist or not. If we consider China a world hegemon already, then what’s the impact of hegemony on the working masses in China and the masses across East Asia, and what’s our progressive alternative? We haven’t had the space to discuss these issues enough yet.

Looking ahead, Hong Kong has been handed over to China for more than 20 years, and the mass movement in Hong Kong should think about the future of Hong Kong and China as a whole, linking the future of democracy in Hong Kong with the movement of workers and peasants in mainland China who are struggling to defend what little rights they have. Even in the most difficult times, in mainland China and Hong Kong, there will be people who dare to persevere. People will keep exploring in the darkness, and at the right time they will open a way out. We should uphold such a belief.

LC: What would you say to those who doubt the meaningfulness of the June 4 remembrance in Hong Kong?

LCL: I would say that I think it’s still very meaningful. After 1989, Hong Kong became the only place in China to commemorate June 4 publicly, and where the public could participate very actively. This shows that Hong Kong people’s pursuit of democracy and the desire to take an unambiguous moral stance are precious traditions. Public commemoration and a decades-long history of cross-border solidarity with activists on the mainland can’t be swept away so simply.

China’s dictatorship and monopoly capitalism didn’t change after June 4. Although there may not be any immediate result, if we continue, our message will sooner or later resonate with the mainland. From a leftist perspective, we see that cross-border worker solidarity is the only way forward. This is especially true in South China, particularly in Guangdong, where a civil society movement has taken inspiration from experiences in Hong Kong, with visits by mainland activists to Hong Kong and even participation in the June 4 vigil. We must continue to speak up—It is totally unrealistic to imagine that freedom can be allowed in Hong Kong in exchange for not questioning Chinese dictatorship.

Finally, we shouldn’t just commemorate the day of June 4 every year and be done with it. Our goal should be to use the commemoration as a vehicle to explore the way forward for democracy in Hong Kong and on the mainland simultaneously. If the vigil doesn’t develop into an actual promotion of the struggle for democracy in the whole of China including Hong Kong, and doesn’t emphasize the mutual reliance of people in China and Hong Kong in their struggle, then the commemoration will indeed be reduced to a ritual of little significance.

Lam Chi Leung was born in Hong Kong and studied at Jinan University in Guangzhou. As a Marxist and socialist, he participated in the student movement in 1986 and the solidarity movement with students in Beijing in 1989. He returned to Hong Kong in the early 1990s and has participated in local social movements ever since. He is currently a member of Left21 and the editor of “Selected Writings of Chen Duxiu in his Later Years.”

Footnote

- Jiang Zemin famously used this aphorism「井水不犯河水」in 1989 to argue that Hong Kong people should stay out of mainland Chinese affairs, especially when it came to criticizing the events of 1989.

- HKFS pulled out of the June 4 vigil in 2015, after government repression ended the Umbrella Movement. Former HKFS Secretary General Alex Chow urged student unions to remain in HKFS but acknowledged it was difficult for many to chant these slogans about a democratic China.