Every year during late winter and early spring, atmospheric pressure dips over the two deserts of the Taklamakan and Gobi, feeding into the strength of the westerly winds. As they interface with eroding landscapes, its sand and loose top soils are picked up, transitioning into the air and into a dust storm.

In April and May of last year, a storm swept across areas in southwestern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), covering cities including Aksu, Kashgar, and Hotan in its heavy yellow dust. Disruptive for the eyes, visibility was down to five meters in some parts of the storm. The particulate matter delayed trains traveling along the “Belt and Road” for several days. People were forced to take shelter indoors and all flights in and out of Aksu and Kuqa were cancelled, including 48 flights later cancelled in the capital Beijing. Activities froze as sand threw place into a turbid haze.

The dust storm has become an annual occurrence compared to half a century ago, when each phenomenon struck only once every seven or eight years. The sands are close reminders of the expanding deserts from the nation state’s peripheries, “Xinjiang” and Inner Mongolia.1

A rail line initiated by US tech conglomerate Hewlett-Packard (HP) speeds through the growing deserts of this region, where its optimization of commodity movements are paired with spatial designs that have slowing the desert as their top priority. Nevertheless, as the deserts expand roughly 2,000 square kilometers a year, each grain of sand carries the potential to be thrown across thousands of kilometers with the storm, riding air currents sometimes as far as California, unbound by jurisdictions.

The Chinese state and HP signed the agreement to begin construction of this rail line in 2014. Most of the goods transported through this route are from multinational IT companies whose manufacturing is situated in Chongqing, central China. This followed a move made by the company, as well as others including Foxconn who supplies Acer, Apple, and Volkswagen, to shift their factories towards China‘s western border.

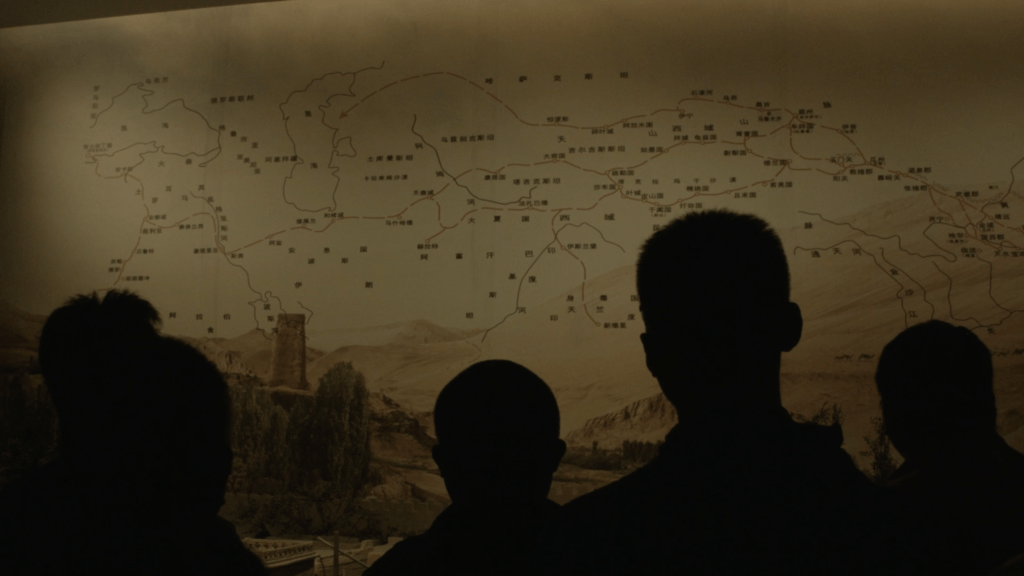

In order to understand just how enmeshed states are through this transnational tech and infrastructure cooperation, it is necessary to think at multiple scales: not only the space that a rail line cuts through but also the atmospheric stream that flows and interfaces with it. The winds form a big part of how the land behaves through the desert spaces of the Taklamakan and Gobi. The Taklamakan spreads across the province of Xinjiang, a so-called autonomous region covering an area bigger than France, Germany and Spain put together, and sharing borders with Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and India.

We can examine the western Chinese rail line across further scales: the scale of the frontier space, where state-led development projects dot the western Chinese territories; the scale of the Special Economic Zone (SEZ), which produces and is composed of replicable spatial technologies that bring outside markets into state spaces; and finally, HP’s logistical innovations across time and transnational space, which necessarily involve the global scale of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

By using scale-as-method, we become sensitive to how scale is mobilized within a multitude of processes, where minute but fundamental changes at the level of, say, inventory lists scale up to matter in physical, cartographic, temporal and cognitive ways. But scale-as-method also gestures towards what Gabrielle Hecht describes as a multi-scalar approach—here the dust storm as an interscalar vehicle undoes the idea that the scales listed above can even be considered distinct, not only on a narrative level but materially as well. Scale-as-method thus pulls into relation time and spaces which have long been kept separate.2

1.0

Frontier

Over the past several decades, state officials have told various communities of farmers whose lands fall within the path of these annual sandstorms to rearrange their plots of land by converting their cultivated ground into rows of bushes, shrubs or trees. These efforts are part of the “Three-North Shelter Forest Program,” a large-scale state-led civic movement combating desertification and controlling dust storms. This program enforces the state directive to collectively plant forests aimed at securing deteriorating soil to the ground, while offering cash incentives to farmers to plant trees and shrubs in areas outside their farm lands that are more arid. Shrubs and trees serve as a windbreak from dust storms and encroaching deserts.

The program started in 1978 and is planned to be completed around 2050, with forests now covering more than 500,000 square kilometers—the largest artificial forest in the world. The state has mobilized political and scientific rhetorics of warfare to justify this monocultural program: The People must fight the degradation of land, pushing it back through feats of modern engineering, just as they fight enemy nations. For art historian Asia Bazdyrieva, this personification of the changing climate as enemy is on par with the othering of populations. The Cold War legacy of the binary of friend and enemy, in which a rhetorical other to fixate on proves useful to shore up in-group support, manifests here as dual enemies of the state.

These rhetorics follow a familiar chorus: In the 1960s, as clashes increased along China’s borders, the desert regions of Xinjiang were one of the first areas to be militarized and industrialized by Mao Zedong’s programs in order to prepare for war with the Soviet Union. This also had the benefit of mass mobilization through campaigns to “green the motherland.”3

The 1975 documentary Spring in the Desert and the 1965 film Army’s Reclamation and Battle Song chronicle the ambitions of China’s Han ethnic majority to build dams and farms in desert and barren lands. These projects were carried out by local militia and “educated youth” from China’s interior provinces, who were sent to carry out large-scale development projects in “remote places.” Such grand greening projects were implemented in otherwise undeveloped and famine-stricken Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia and, rather than improving the poor conditions, only sidelined the already marginalized local ethnic minorities. From the late 1950s, the “Northwest China and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Desertification Control Plan” distilled a desertification governance system whose policies and regulations called on local government departments, communities and social groups to participate in controlling the desert, promoting afforestation programs until economic reforms, and the establishment of the Three-North Shelter Forest Program in 1978.

Distinctive patterns of colonialism were encoded within the modernist project of Chinese Communism, with the scale of the frontier being crucial in defining the perimeters of nationalism. Through the sanitized rhetoric of engineering, the shaping of the physical environment came to stand in for the colonial dispossession of local populations, catering to extractive forms from cultivation to plantations. As film scholar Li Cheng notes, these dimensions of colonial enclosure become solidified as the greening of ethnic borderlands effectively sinicizes the minorities that inhabit these margins.4 Where previously yellow sands surrounded the landscapes, now green waves roll across them like the ocean.

Legitimizing the regime through these projects allowed for the enveloping and displacement of indigenous populations within the political unit of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This entails a dismissal of indigenous knowledges and forms of relating to their land. Uyghur people had previously used an extensive network of karez, a localized technique which had irrigated arid areas for millennia. The hydraulic system provided reliable drinking water and distributed snowmelt water from the faraway Tianshan mountains toward crops, across what was deemed to be the second lowest point in the world behind the Dead Sea. These indigenous infrastructures were replaced by the PRC’s large-scale agricultural projects; cotton plantations, for instance, were made unusable because of oil field pollution or over-exploitation by deep wells, which resulted in rapidly receding water tables.

This new extractive vision of the frontier space was fundamentally incompatible with what indigenous peoples had practiced for thousands of years. Since the 1950s, and accelerating over the past few decades, utopian social-agricultural experiments of high Maoist socialism have completely drained groundwater and many lakes across Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia. These projects and the resulting dried out lakes and riverbeds are key sources of China’s annual dust storms.

Atmospheres and geologies continue to be posed as an “engineering problem” to this day. Anthropologist Jerry Zee writes on Chinese governance as the “’programming and modulation of more-than-human processes,” that consider the social, botanical, market, aeolian and political processes as manipulable components of an ‘environmental machine.’”5 The designing of desert spaces into crosshatches of forest are supported by “countless laboratory experiments involving computer modeling and wind tunnel tests,” where models and tests siphon colonial histories of dispossession and categorize them as unquantifiable data, of no use value.6

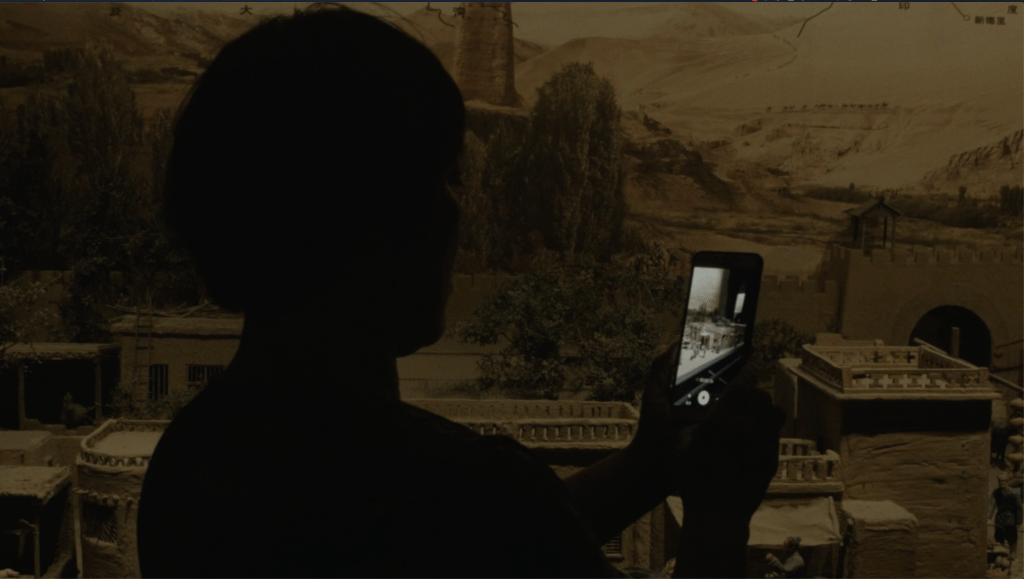

Instead, value is found through various forms of occupation in the region. The tourism industry has been important in this respect. During the first half of 2019, 310,000 ethnically Han tourists visited curated locations from the Taklamakan desert to the Tianshan mountains. State campaigns welcome travelers from the wealthier Eastern coast to visit beautiful, natural vistas not far from sites of the ongoing mass incarceration and dispossession of local Muslim and Turkic-speaking minorities. Glossy images of tourist sites and enjoyment create a happy veneer, obfuscating the everyday realities of dispossession and extractive capital perpetrated by the state. At the same time, it is through these images and imaginaries that onlookers and settlers alike absorb cultural-economic justifications to further “open up” the region through massive profit-taking.

2.0

Zone

The 2014 rail line agreement between HP and the Chinese state was “defined not only according to business logic, but also with certain strategic calculations.”7 Saving two weeks’ worth of transportation time, it was faster than ocean-ways and cheaper than airfreight. This rail route from Chongqing cuts through Xinjiang into Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, and Poland, before reaching its destination in Germany, 11,180 kilometers later. It was seen to be an alternative to the Pacific Ocean route, which was filled with chokepoints and other perils. But this rail line and the BRI would not have been possible without the success of the state-led “Go West” campaign that began in 2000.

The “Go West” campaign encouraged heavy industries and corporate manufacturing facilities to move inland and westward, to “thrust Great Development” from the vibrant east coast into its poorer regions through a controlled but loosened economic climate.8 The region not only contains the country’s largest coal reserves, but a vast reservoir of oil which forms the foundation of Xinjiang’s energy economy. Oil had already been surveyed in the region as far back as the Qing period (1644-1911). Though it was only after 1917, when the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union funded and designed a Central Asian rail-transport network, that the oil fever was ignited. Surges in demand for the resource grew rapidly after the 1990s and accelerated with the “Go West” campaign, in which investments totaling US$300 billion poured into 685 projects in Xinjiang in 2014 alone.

The overall development campaign was a state-led movement into energy and resource-rich regions, touted as a redistribution of wealth from the affluent eastern coasts, westwards and inwards into poorer regions. Whether by long-distance connections to industrial zones, or consumer demand from outside the country, the strategies and logistics of zones of exception—the generative and segmented remaking of territory—have become intrinsic to modern statecraft. Now, 20 years on, these “strategies” have proven to not only be unsuccessful in smoothing over regional inequalities but even exacerbating them to the continual and disproportionate benefit of the Han ethnic majority. The cumulative effect has been raising the region’s GDP while retaining the wealth gap between China’s East and West.

By 2014, importing Chinese-made goods to western markets became increasingly attractive as transportation speeds increased and costs fell. Transnational corporations like HP leveraged such incentives in their favor, and the 2014 rail line became an integral part of the BRI in 2015. The rail line marked the beginning of a cascade of what is now five continental mega-infrastructure projects collectively known as the BRI, including the development of telecommunication cables, railways, dams, power stations. The massive campaign also provides funds and a labor force to implement these projects predominantly across the Global South, totally US$1.2 billion worth of Chinese construction-firm contracts in over 60 countries.

Integral to the BRI and the HP rail line has been China’s signature adaptation of SEZs. Since President Xi Jinping came to power in 2013, the catchphrase used amongst planners of the BRI is youwai zhinei (由外至内), meaning “bringing the outside in.” This logic, brought to life through SEZs, sees the export-process economy driven by transnational capital entering the system of China’s state-controlled economy. Environmental and labor deregulation offers legal independence from the domestic laws of the host country through the creation of “zones” in which pools of cheap labor are further entrapped by tax incentives.

Anthropologist Aihwa Ong writes that within the Chinese Communist state system, zoning technologies are devised as a distinctive way to re-territorialize national socialist space while ensuring the controlled development of capitalism.9 These technologies redesign and recast geographies of law and violence through the rearrangement of the inside and outside of state space. Actions like military occupations, land grabs, and dispossessions are all part of this technocratic territorial reconfiguration, all of which have accelerated after Xi abolished presidential term limits in 2018.

3.0

Hewlett Packard

But beyond business logic, what strategic calculations inform the decision by a US tech company like HP to build actual rail lines in the first place? Not concerned solely with the scope of IT infrastructure and moving commodities, HP’s interests include hegemony over the entire transnational distribution route through advanced supply chain management.

The beginnings of supply chain management can be found in places previously occupied by US military forces during the Vietnam and Korean Wars. This confluence of US imperialism and capitalist supply chain management trialing enabled the surge of transnational supply chains that form the backbone of global capitalism today. By the 1970s, firms in the industrializing Global North were experiencing a downturn in profits due to rising production costs and wages, and sought cheaper alternatives elsewhere. Charmaine Chua has argued that firms returned to older colonial modes of production, where seeking the extraction of resources and cheap labor internationally allowed for profit to be reaped in the Global North while offshoring production to the Global South.10

At the same time, a new type of supply chain management emerged in late 1970s Japan. The car manufacturer Toyota pioneered moving production outside Japan’s sovereign borders, coordinating space and time in a more cost-beneficial manner. As a flexible production technique, just-in-time (J.I.T.) management aimed to shave off expenses, where possible, through various methods of tweaking and “optimization.” J.I.T., in many ways, is a capitalist innovation, developed in the shadow of Japanese imperialism and Japan’s new role as junior partner to US empire in the Pacific. Fittingly, HP was the first western company to incorporate Japan’s pioneering industrial methods of supply chain management.11

J.I.T. management pioneered a rationalization which seeks calibration of work throughout the whole body of the supply chain. This technique standardized the entire production line, with working hours described by Stefano Harney as a “killing rhythm of labor.” Such a rhythm globalizes an acceptance of working the body at a rate which physically and mentally destroys a person over time.12

“Efficiency” is implemented at different scales: within strata of inventory lists to political economic agreements along the HP railway. Thousands of laptop computers and accessories are piled neatly in sealed shipping containers to travel across the rail route between Chongqing and Duisburg three times a week. National borders have also transformed: Goods are allowed to travel freely along the rail line through Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus. With impediments such as security checkpoints removed, HP is pushing neoliberal ambitions of free trade further than ever before.

HP has also negotiated with the Chinese government to implement their own border customs software for processing documents, permitting its containers to instead stay locked and uninspected at border crossings en route. For instances where cargo inspection still occurs, quarantine, and customs clearance now occur in one stop. This state-corporate partnership has installed a new framework of transnational regulation, security and labor management, along with standardized units across platforms. In these digital spreadsheets and inventory lists, bodies and environments of distribution disappear across transnational space, giving the capitalist imaginary a naturalized, seamless flow that obviates, and in fact evades, notice.

One does not have to look far to see that this free flow of goods and capital entails an arresting of movement for others. Since the development of this rail line and the broader BRI, faster trade through these overland lines has meant increased enforcement of restrictions for local Uyghur, Turkic Muslim, and other indigenous peoples and ethnic minority groups. In 2016, many from these communities were told to hand in their Chinese passports to local authorities for “examination and management.” The region has been heavily policed for forms of “separatist” and “terrorist” activity. This ranges from daily identity and mobile phone screenings, WiFi sniffers, cars with compulsory tracking devices, to one meter of resolution available through satellite imagery. Xinjiang is currently the key test zone for the entire country’s artificial intelligence operations.

Such oppressive fixity is the dark side of the fantasy of logistics. Such desire accumulates power through the facade of an all-encompassing smooth operator, adept at hiding the fact that it needs friction in order to stay in business. Friction, as anthropologist Anna Tsing defines it, is the awkward, unequal, and unstable force that “refuses the lie that the global operates as a well-oiled machine.”13 Understanding these global points of friction is exactly what allows HP to maintain its market dominance, where what is at stake for them involves finding logistical solutions for keeping costs low. Speed, then, is engineered across frictions traversing between the body and continents.

HP’s innovations for the BRI aligned with the national interests of the Chinese state because these joint plans assisted the westward movement of industries toward Xinjiang. The consequences of this collaboration are growing ever more grim, as the state-corporate “mitigation of risks” involves both the violent arresting of Uyghur and other Turkic, indigenous, and ethnic minority populations along with the increased deterioration of their lands. The implications of these logistical calculations are disturbing ecologies as well as societies, and it is with this urgency that these processes need to be seen together as two sides of the same coin.

4.0

Railway

The rail line and other BRI projects traverse terrains that are amongst the most affected by climate change, with its long distance infrastructures needing to be designed in ways to withstand increasingly erratic weather events. The railway required 500 kilometers of windproof walls, necessary to shield trains against the Gobi’s powerful gales. Rows of grass, bush, nets and stones all form a risk management scheme against the force of wind and the phase transition of desert into storm.

Since 2017, more than one million primarily Uyghur but also other indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities have been “disappeared” into “re-education camps,” and in the following years, a government-led labor transfer scheme has forced prisoners from these re-education prison camps into the very factories of HP as workers. Other transnational corporations operate factories in the region that use forced labor such as Acer, Apple, Volkswagen, and Foxconn, amongst many other international companies.

The carceral continuum between labor camps and supply chain capitalism is plain for all to see. Deborah Cowen writes that the neoliberal management of life and death and its anti-political calculations, cost-benefit analyses, and market-driven logics embed themselves in the most minute of measures. Time and space are designed with technologies of efficiency and standardization, eliminating resistances that may include possibilities of political claims or ruptures. The management and security of the life of the whole supply chain—not just the population it serves—is crucial.

It comes as no surprise, then, that HP was not only complicit across its supply chain territories, but actively designed and provided the technology to make the racist population control of colonial occupation in China possible. Similarly, in Israel, HP provides IT infrastructure and support services for the Israeli army and police, while also underpinning the system of biometric ID cards, facilitating the militarized settler control and surveillance of the colonized Palestinian population. HP’s ambitious control of transnational supply chains thus plays a central role in “technology-enabled racism” within multiple settler colonial and apartheid regimes.

5.0

Toxic Constellations

As millions of laptops and computer screens wend their way across China toward Western markets, the sandstorms stubbornly continue eastward. These displaced dusts and sands have, too, become products themselves, manufactured as an accumulation of soil degradation, labor practices, atmospheric sways, political ideologies, and geological grinds.

The contemporary dust storm moves through a series of chemical transformations, where during their long-range transport, its particles collide with bacteria, gases, and coagulated solid particles. “The dust with pollution aerosols, such as industrial soot, toxic materials, and acidic gases” travels over China‘s heavily industrialized zones.14 Particulate matter is then scattered, congealing into a whole new series of constellations, embroiled with manufactured and chemical residue.

These afterlives of unevenly distributed, corporation-led harm ravage the urban remnants of high-carbon industrial practices, extractive economies, and settler colonialism. The dust storms bring a sense of environmental uncanniness; modernity is materially readdressed by the unintentional consequences of its own grand designs.

Landscapes remain not backdrops but instead peripheral deserts that appear inside the metropolises of Beijing, Seoul, California; frontiers become centered, bringing the outside in. Memories of malpractice, toxic fingerprints, and suspended futures fold into each other and reproduce through toxic constellations.

Calculations of speed and smoothness along corporate supply chains have woven together the state’s biopolitical control of the local Uyghur, indigenous, and ethnic minority populations with its fight against increasingly strange weather. Though by the design and engineering of immediate time and space, the long-term, delayed effects of industry and capital form what Rob Nixon would call a temporal disjuncture, a dislocation of causal relations across space.15 Such geographies of concealment diffuse and obscure the truly global nature of settler colonial dispossession and genocide. Seemingly separate ecological, labor, and indigenous struggles can be unified in the collective struggle against settler coloniality.

Part of this process must hold companies like HP and their globally distributed production accountable for utilizing and supporting the mass incarceration of indigenous populations. But we must also interrogate narratives that prioritize “progress” and economic wellbeing as they too often spring from racist and exclusionary ideologies. This must go hand in hand with denaturalizing green rhetorics—where afforestation, solar power and clean energy are often complicit with settler occupation of lands all the while displacing environmental devastation to some elsewhere. Finally, critiques limited by national boundaries will only reinforce the global nature of capitalism’s inherent self-concealment by obscuring the transnational reach of dust storms, supply chains, and settler colonial exchange of technology and capital.

By re-evaluating each scale that is deployed across this rail route—from the frontier spaces where wars are being waged against growing deserts, the technologies of spatial inversion of SEZs that bring outside markets in, the entire bodily expanse of a supply chain, to the closer lens of the the corporate and state railway collaboration—we pierce our modern geographies of concealment and bring into view the lattice of violent relations that sustains the modern state of China and its international markets.

Footnotes

- This essay focuses in part on the mass detention experienced by Uyghurs. The CCP’s tactics of mass detention and surveillance affect many communities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR, also known as “Xinjiang,” “Northwest China,” “East Turkestan,” “Uyghuria,” “Ghulja,” “Tarbagai,” “Altay,” “Dzungarstan and Altishahr,” and/or “Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin Region,” and which will henceforth be referred to as “Xinjiang”), most visibly Uyghurs but no less significantly other indigenous and minority ethnic groups. A highly contested term, the proper name Xinjiang (新疆) was first used by the 18th century emperor Qianlong, and conferred on the XUAR upon Zuo Zongtang’s reoccupation of the region in the late 19th century. In Mandarin Chinese, it means “new territory,” “new border,” or “new frontier.”

- Gabrielle Hecht. 2018. “Interscalar Vehicles for an African Anthropocene: On Waste, Temporality, and Violence.” Cultural Anthropology 33 (1): 109-141.

- Judith Shapiro. Mao’s War against Nature Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Cheng Li (2017) Sinification by greening: Politics, nature and ethnic borderlands in Maoist ecocinema, Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 11:1, 46-68, DOI: 10.1080/17508061.2016.1269479

- Zee, Jerry. 2017 “Holding Patterns: Sand and Political Time at China’s Desert Shores.” Cultural Anthropology 32 (2): 215-41.

- Williams, Dee Mack. “The Desert Discourse of Modern China.” Modern China 23, no. 3 (1997): 328-55. Accessed December 9, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/189126.

- “Battle of the Silk Road: Kazakhstan reformats the map of Eurasia Logistics,” Center for Strategic Assessment and Forecasts, December 21, 2015, accessed July 25, 2017, http://csef.ru/en/oboronai-bezopasnost/326/bitva-za-shyolkovyjput-kazahstan-pereformatiruet-kartulogistiki-evrazii-6468.

- James A Millward, Eurasian Crossroads: a history of Xinjiang. (London: C. Hurst, 201), 322.

- Aihwa Ong, “The Chinese Axis: Zoning Technologies and Variegated Sovereignty,” Journal of East Asian Studies 4, no. 01 (2004): 72, accessed August 13, 2017.

- Charmaine Chua, “Turbulent Circulations,” Skype interview by author. May 05, 2017

- Marc A. Weiss and Erica Schoenberger, “Peter Hall and the Western Urban and Regional Collective at the University of California, Berkeley,” Built Environment 41, no. 1 (2015): 69, doi:10.2148/benv.41.1.63.

- Wesley Attewell, “Vietnam Logistical Archives,” Skype interview by author. August 9, 2017.

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton University Press, 2015), 6.

- Yele Sun et al., “Chemical composition of dust storms in Beijing and implications for the mixing of mineral aerosol with pollution aerosol on the pathway,” Journal of Geophysical Research 110, no. D24 (2005). doi:10.1029/2006jd008032.

- Rob Nixon, “Slow Violence, Neoliberalism, and the Environmental Picaresque,” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 55, no. 3 (2009): 449.