Originally published in Against the Current. Republished with permission.

Since its founding in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a global infrastructural development project of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that stands as a major plank of its diplomacy, has been at the center of debates about the Chinese government’s political orientation and intentions.1

For socialists, these debates cut to the heart of the class nature of the Chinese state and its implication in processes of imperialism. Apologists for the Chinese Communist Party have gone so far as to frame the BRI within the ideals of socialist internationalism, “genuine compassion,” and “building humanity,” albeit within the dynamics of global capitalism.

More critical and robust assessments find that the BRI is an intensification of global capital accumulation, marked by state capitalism and public-private partnerships mobilized to facilitate the rise of a new multipolar imperialism for the benefit of Chinese capitalists and political elites. As socialists analyzing the geopolitical and economic ramifications of China’s entrenchment in the global neoliberal system, we must not lose sight of the on-the-ground impact of China’s overseas investments.

Indeed, such a viewpoint is a necessary component of critiquing the claims of the Chinese government and its defenders that the BRI is a win-win program of mutual development driven by socialist ideals. If such were the case, it would result in rising prospects and power of local workers’ movements and facilitate the reversal of structures of inequality and exploitation. The case of Jamaica demonstrates the opposite.

When I first went to Jamaica in 2012 as a graduate student studying the environmental politics of the Maroons, an Afro-Indigenous community who freed themselves from enslavement in the 18th century and established an autonomous society in the mountainous interior of the island, Chinese overseas development policy seemed irrelevant to my work. Yet as my field research progressed over the following eight years, first as a doctoral student in African diaspora studies and then as a post-doctoral researcher, the impact of Chinese infrastructural development and extractive industry on the Jamaican people and environment became increasingly apparent.

The timing of my field work overlapped with an unprecedented surge in Chinese economic and diplomatic engagement with Jamaica and the Caribbean as a whole.

Between 2005 and 2021, the China Development Bank and the China Export-Import Bank loaned USD$2.1 billion to the Jamaican government and state-owned enterprises (SOE), a significant proportion of the estimated $9 billion loaned to the nations of the Caribbean Community in the same period.2

In 2014, as I became well-immersed in the daily life of the Maroon village of Accompong, the state-owned China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) made front page news for opening the historic cross-island North-South Highway (also called Highway 2000) at a cost of over $700 million.

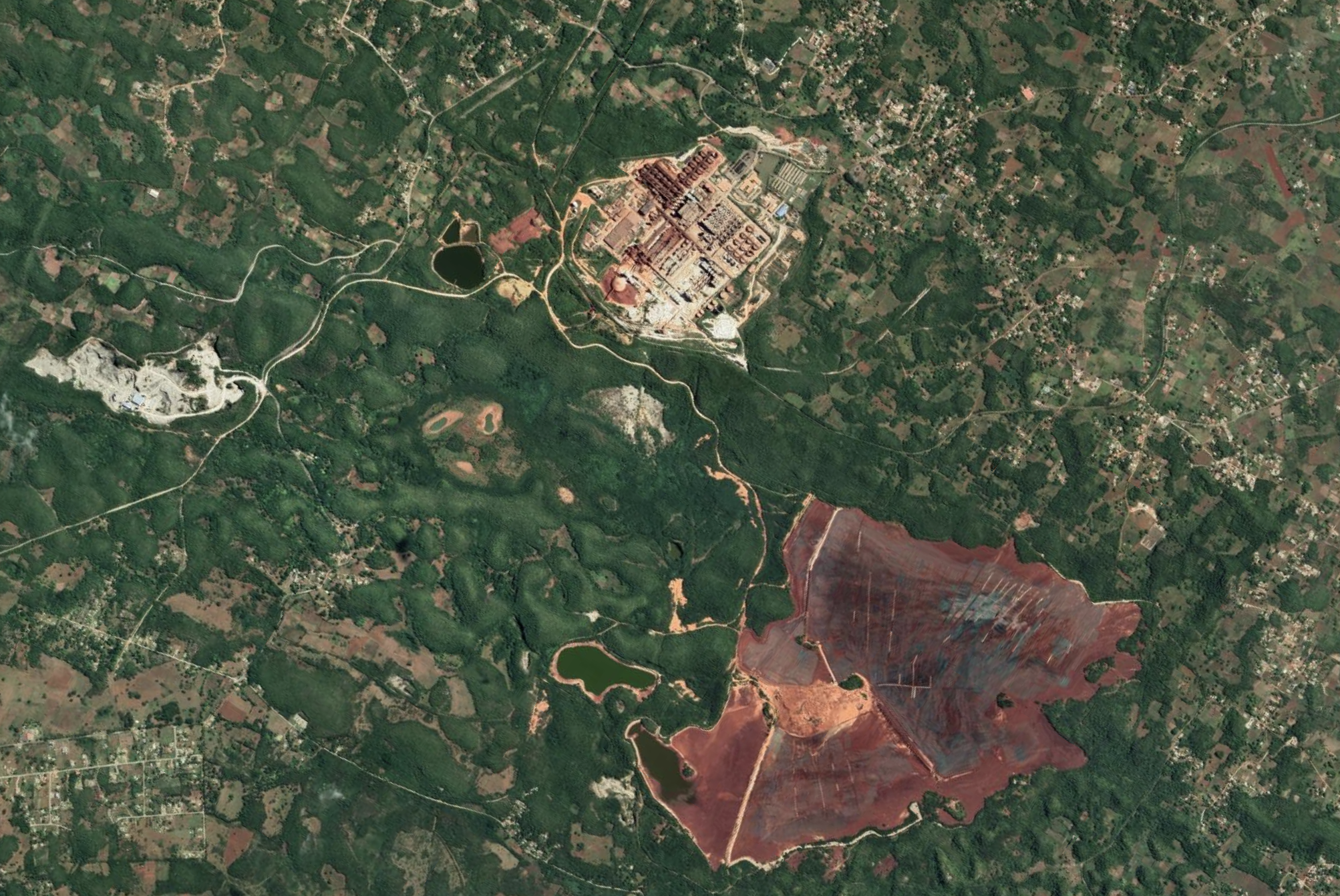

In 2016, the Jiuquan Iron & Steel Group (Jisco), another major Chinese SOE operating under the aegis of the BRI, purchased a bauxite (aluminum ore) mine and refining plant near Maroon territory. Increasingly, my daily conversations with my research respondents became peppered with concerns and experiences dealing with the Chinese economic power sweeping the country. Then in April 2019, Jamaica formally joined the BRI under circumstances of increasing domestic concern about the mounting debt to China.

Chinese development initiatives have acted to further increase the precarity of Jamaican workers and farmers while leaving the country in an economically dependent and indebted position.

With these experiences in mind, this article will discuss and analyze the consequences of the BRI in Jamaica within the context of the island’s historical experience of neocolonial debt, environmental exploitation, workers’ struggle and Indigenous struggle.

Drawing from my ethnographic, political and ecological research, I take a grassroots view of the BRI in Jamaica, centering the experiences of those directly affected by the development projects of the BRI. As such, this article will focus less on analyzing the BRI as grand geopolitical strategy, and instead emphasize how Chinese development initiatives have acted to further increase the precarity of Jamaican workers and farmers while leaving the country in an economically dependent and indebted position.

Empire and debt in the making of Jamaica

Jamaica’s encounter with the PRC long predates the founding of the BRI. In 1972, Jamaica was among the first group of countries in the English-speaking Caribbean to establish diplomatic relations with China. The first Chinese diplomats on the island would have found a country still reeling from the legacies of colonialism, with British rule only having ended in 1962.

Over 400 years of genocide, slavery and plunder by European empires (first under the Spanish and then the British) left the country underdeveloped and dealing with immense socio-cultural traumas. A rigid and racialized class system3 persisted after British rule, and what infrastructural capacity the country had was geared toward facilitating resource extraction, the main exports being sugar throughout most of the colonial era and bauxite upon independence.

Furthermore, Jamaica in the 1970s was a nation rapidly descending into mass violence and chaos as the United States further entrenched its role as the regional hegemon, taking over from the defunct British Empire. A self-described democratic socialist Jamaican government, upon introducing much-needed wealth redistribution and social welfare programs, faced a violent backlash from right-wing forces in the form of gang warfare, allegedly fueled by the CIA.

Tit-for-tat street battles, an exodus of professionals and skilled workers, and rising import prices due to the 1970s oil crisis, paved the way for the unsustainable debt for which Jamaica would become famous in the 1980s and ’90s and into the 21st century.

It is beyond the scope of this article to detail the political economic dynamics and immense social impact of debt in Jamaica over the last 40 years.4 Suffice it to say that the island became a byword for structural adjustment during this period, with every new loan from the World Bank, or default on payments thereof, coming with International Monetary Fund-mandated austerity.

Health and education were notable casualties of this socio-economic assault. By the start of my field research, Jamaican child mortality had almost doubled over the span of a single decade while completion of primary school dropped from 97% to 73% in the same period. This despite the fact that Jamaica had already repaid more money than it had been lent, with continuing debt servicing accounting for a 106% debt-to-GDP ratio according to the latest World Bank figures.

All this is only a small snapshot of the catastrophic outcomes of debt wielded as a tool of neocolonialism.

With the island’s status as one of the most indebted countries on the planet, Chinese infrastructural development was received with fanfare from Jamaican elites, a possible economic lifeline out of the debt trap. The aforementioned highway opened by CHEC in 2014 was greeted by then Prime Minister Portia Simpson-Miller as an “emancipendence” gift.

The tourism trap

My research respondents were more circumspect about the “Beijing Highway,” as it was commonly called. Since Jamaica needed a Chinese loan to finance the highway, CHEC was granted the right to own and operate the highway for 50 years as part of the arrangement. Also, the tolls collected on the highway cannot be used for debt-servicing and, rather, go directly to CHEC as profit.

Additionally, the tolls are astronomical by local standards; to drive the length of the highway in a standard car costs the equivalent of over $12 each way.

This is well out of reach for the vast majority of Jamaicans, where the average monthly salary is around $600 and only 60% of workers have a waged or salaried position at all. Many of my research respondents wondered: for whom was this highway?

The answer may lie in the additional concessions granted to CHEC, primarily 1200 acres of land along the highway to be held in perpetuity. Apparently, this will be used to construct hotels and adjoining infrastructure by Chinese companies for Chinese tourists, a kind of economic enclave from which the locals would not directly benefit, as acknowledged by the then Jamaican Minister of Transport.

This gestures to another dynamic of the BRI in Jamaica, where Chinese SOEs bring in their own workforce from China operating under their own labor conditions and laws. Jamaican trade unionists complained that Jamaican workers were generally not hired for CHEC projects, and in the few cases where they were, the denial of labor rights was so egregious that it led to a strike.

Thus, for all the official cheerleading around this “gift” of the BRI, Jamaica now has a pristine (and quite empty) highway that local workers did not build, that most Jamaicans cannot use, that the Jamaican government does not own, the profits of which do not stay in the local economy, and which will primarily serve as an enclave owned and operated by foreign companies for foreign tourists.

As disappointing as the outcomes of the North-South Highway were for the hope of internationalist solidarity from China, the risk of a far more catastrophic clash between Jamaicans and the BRI emerged with the purchase of a bauxite mine and smelter by Jisco in 2016.

Bauxite mining is deeply intertwined with legacies of colonialism, environmental destruction, and the struggle for indigenous rights in Jamaica. In 1952, the interests of Britain and a group of mining corporations coalesced to establish the bauxite industry in Jamaica.5 The island would become a leading global exporter of bauxite and alumina,6 although there would be little benefit to the people in proportion to the cost of mining.

Between 1952 and 1990, some 62,735 acres of land had been extensively damaged by bauxite mining, which had also displaced thousands of families.7

Pollution is also a major risk of mining, with public health surveys of Jamaican bauxite production centers recounting that “the excavation and transportation of bauxite materials left behind clouds of red dust . . . and a fine layering of red covers much of the scene, spreading far downwind … there prevails a distinct, acrid smell of bauxite dust in the air.”8

Maroons against mining

Given the despoliation entailed in bauxite mining, the community and leadership of the Jamaican Maroons view mining as an existential threat to their society.

The contours of contemporary Maroon struggle and the legacies of resistance they bring to bear in fighting to preserve their land, sovereignty, and culture cannot be discussed in detail here.9 Briefly, Maroon societies emerged from the sociogenic processes of collective struggle against enslavement when captive Africans and their descendants in the western hemisphere fled their bondage and defended themselves against recapture through guerrilla warfare.

Since enslaved labor was central to colonial capitalism in the Americas, the slave-holding states expended great effort in suppressing Maroons as an existential threat to their plantation economies. However, the Jamaican Maroons, against great odds, fought the British to a standstill and forced the empire to recognize their freedom and territorial claims in 1739.10

Today, the Maroons live on as one of humanity’s great cultures of resistance, embodying a tenacious praxis of struggle from below, the present-day target of which is defense of their land at all costs. It is hard to overstate how important the integrity of their environment is to Maroon culture and physical survival.

The Maroon village of Accompong is situated in a unique and ecologically sensitive region named Cockpit Country, the last contiguous rainforest of Jamaica. This is an area claimed by the Maroons as their historical territory won during their ancestors’ fight for freedom in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Many of my [Maroon] research respondents, prominent leaders among them, consider mining in their territory to be an act of war.

The Maroons today live as mostly small-scale cash-crop farmers and are dependent on Cockpit Country for their livelihoods and the memory of their ancestral struggle, the fountainhead of their culture. Since the mid-2000s, when Accompong became aware of plans to mine Cockpit Country for bauxite, the autonomous community has played a leading role in an unprecedented anti-mining coalition of environmental non-governmental organizations, activists, academics, and local stakeholders reflective of the high stakes of the struggle.11

Jisco’s reopening and expansion of a bauxite mine a mere 20 miles away from Accompong escalates the stakes of Maroon struggle to dangerous proportions. Indeed, many of my research respondents, prominent leaders among them, consider mining in their territory to be an act of war.

Jisco has made no attempt to consult with the Maroons on their plans, and although they have not yet expanded their operations into Cockpit Country proper (their location lies in the lowlands at the edge of the geological and cultural boundary), company representatives have publicized plans to more than double output of the refining facility and expand the mines by hundreds, if not thousands of acres.

Residents of the areas around the mine have complained of damage to their health due to air and water pollution, only to be stonewalled and undermined by Jisco. Compounding these problems is Jisco’s acknowledgment that the displacement of farmers will be necessary as the mines expand.

All this is adding to the fear and apprehension in the Maroon community about Chinese intentions, and they share the concern of many Jamaicans that the lack of transparency in negotiations between China and their government is fueling the already endemic corruption in their country.

Also, being a country of the African diaspora, Jamaicans are increasingly aware of the horror stories of Chinese exploitation in Africa. Only time will tell how these tensions unfold and, of course, the Maroons and their allies are not passive actors in these events, having already fought to curtail similar mining encroachments from Western companies.

A meeting of revolutionary traditions

If the projects of the BRI have stark parallels with the colonial and neoliberal policies of Jamaica’s past, when the island valued as little more than a servile “paradise” for American tourists and/or an environmental sacrifice zone for the Western aluminum industry, they also have differences in keeping with China’s more novel form of imperialism.

As previously mentioned, Chinese companies often insist on importing their own labor, thus denying what little material benefit Jamaican workers could have received from the BRI.12 They also manage this labor force outside the remit of Jamaican labor laws.

This, combined with a Chinese SOE (CHEC) being granted a large land grant as partial compensation for infrastructural development, represents what scholar Ruben Gonzalez-Vicente calls “embodied transnational sovereignty,” where China is able to circumvent Jamaican sovereignty, including customs duties and taxes, for the realization of profit.

China has, in effect, transposed its own exploitative labor conditions to Jamaica. Jamaican elites may appreciate that they can pay back debts with land, and that China does not directly require broad policy changes like the structural adjustment conditions of IMF and World Bank loans.

However, even with the above and the fact that the Jamaican debt to China is small compared to that claimed by Western IFIs and private firms, Jamaican politicians are growing increasingly wary of the costs of doing business with China. In November 2019, Prime Minister Andrew Holness announced that Jamaica would no longer borrow from China, a scant seven months after formally joining the BRI.

As usual, most Jamaicans are not privy to the inter-governmental discussions and deals driving these decisions, but their government’s newfound reticence in engaging with China reflects deeper concerns among BRI partners that the initiative is a debt trap.

In effect, much like the debt repayment structure of Jamaica’s “Beijing Highway” described above, China expects a financial return from its investments such that Chinese companies become the main beneficiaries of a BRI loan while the host country incurs the debt. If profits are insufficient to repay the debt, then China will repossess the project, imperiling host country finances and sovereignty.

This risk is perhaps amplified in the Caribbean where, despite CARICOM’s objective* to coordinate foreign policy for the equal benefit of all member nations and China’s lofty rhetoric of equal partnerships, China pursues bilateral deals with individual states, thus leveraging its greater political economic power in an uneven relationship with smaller countries.

Almost two decades of Chinese loans and infrastructure-led development have left Jamaican workers and farmers as precarious and dispossessed as ever.

Almost two decades of Chinese loans and infrastructure-led development have left Jamaican workers and farmers as precarious and dispossessed as ever. The hard-fought and generational struggle for Jamaican workers’ power (trade unions were instrumental to Jamaica’s independence struggle) has been curtailed and rolled back by China’s transposed sovereignty.

Furthermore, Chinese mining interests appear poised to pick up where their Western counterparts left off in terms of irreversible ecological destruction and threats to indigenous survival. Certainly, Jamaica cannot bear another 50 years of capitalist exploitation and extractive industry.

If there is any hope in turning this dire situation into revolutionary momentum, it will be in Jamaicans making common cause with the Chinese laborers imported to the country. According to China Labor Watch, Chinese workers on overseas BRI projects are often subject to “deceptive job ads, passport retention, wage withholding, physical violence and lack of contracts” to the extent of constituting forced labor and human trafficking.

In fact, at least one Chinese worker in Jamaica has already blown the whistle on such conditions. Unfortunately, as of the time of writing this article, there appears to be no organized effort to make solidaristic alliances among Jamaican workers, Chinese workers, and Maroons. The Maroons are organized as an indigenous community seeking land and sovereign rights, rather than workers seeking class emancipation, and remain locked in a fractious political battle with the Jamaican state toward those ends.

Furthermore, the cultural and language barriers between Jamaicans and imported Chinese workers are significant. Yet both countries have rich revolutionary traditions. If Jamaican labor militancy and Maroon struggle were able to reconcile and align their interests, while cultivating strategic allies among the heavily exploited Chinese workers, a powerful relationship of international solidarity from below could be forged.

Given the regional and transnational diasporic networks Jamaicans and Maroons are embedded in, along with Chinese workers’ connections to their homeland, such potential is made all the more compelling in the possibility of global worker solidarity spreading along the very network of the BRI itself.

We cannot diminish the profound logistical, organizational, and ideological barriers to achieving such a vision, but conversely, the terrain of struggle in Jamaica is now aligned such that previously disparate and distant traditions of revolutionary internationalism are positioned to renew themselves and unite to resist Chinese imperialism, transnational capital accumulation, and the local capitalist class in the Caribbean.

Footnotes

- The extent to which the BRI represents coherent policy on the scale of grand strategy or a more contested, contradictory, and contingent process is an ongoing academic debate (see https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0962629820301177).

- The Caribbean Community, a political and economic union of Caribbean nation-states founded in 1973.

- For foundational social science texts on this complex issue, see: Braithwaite, E. (1971). The development of creole society in Jamaica. Jamaica: Oxford, Claredon Press; Nettleford, R. M. (1970). Mirror, mirror: Identity, race, and protest in Jamaica. London: W. Collins and Sangster. For more contemporary analyses of race and class in Jamaica, see: Meeks, B. (2000). Narratives of resistance: Jamaica, Trinidad, the Caribbean. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press; Thomas, D. A. (2004). Modern blackness: Nationalism, globalization, and the politics of culture in Jamaica. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- The documentary, Life and Debt, covers much of the social dynamics and history of debt in Jamaica. http://www.lifeanddebt.org/

- Davis, C. E. (1989). Jamaica in the world aluminium industry. Kingston, Jamaica: Jamaica Bauxite Institute.

- Alumina is refined bauxite ore that is smelted to produce aluminum.

- Girvan, N. P. (1991). “Economics and the environment in the Caribbean: an overview.” Pp. xv in Caribbean ecology and economics, edited by N. Girvan and D. Simmons. St. Michael, Barbados: Caribbean Conservation Association.

- McBride, D. (2009). “‘Red Marly Soil’: medicine, environment, and bauxite mining in modern Jamaica, 1938 to post-independence.” Pp. 252 in Health and medicine in the circum-Caribbean, 1800-1968, edited by J. De Barros, S. Palmer and D. Wright. New York: Routledge.

- See Connell, R. J. (2017). The Political Ecology of Maroon Autonomy: Land, Resource Extraction and Political Change in 21st Century Jamaica and Suriname. UC Berkeley. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5n1665b6.

- I should note that from the Maroon perspective, the British quickly backtracked and undermined the spirit and terms of the 1739 treaty, thus creating conflicts and tensions between the Maroons and the government over land and sovereign rights that persist to this day (see Connell, 2017).

-

For a more in-depth analysis of the political ecological dimensions of contemporary Maroon struggle and environmentalism in Jamaica see: Connell, R. (2020),

Maroon Ecology: Land, Sovereignty, and Environmental Justice. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, 25: 218-235. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12496

- Even in the instances of Jamaican workers hired by Chinese companies, such as at the Jisco mine, workers live a precarious existence, with one local union charging Jisco with “wanton disrespect” of Jamaica’s labor laws and regulations. https://www.jamaicaobserver.com/news/bitu-accuses-jisco-alpart-of-disrespecting-unions/.