Read this article in Chinese.

On February 11, the UK Home Office published a guidance note that has essentially rejected Hongkongers’ political asylum claims. The note states that protesters “are unlikely to be able to establish a well-founded fear of persecution”—appearing to blame police brutality on protesters’ tactics, while glossing over Hong Kong authorities’ recycling of colonial-era laws to justify their human rights violations.

This seeming abandonment from Boris Johnson’s Conservative government, less than a year after he declared he would “back (Hong Kong people) every inch of the way,” should not be wholly unexpected. The popular notion that Britain symbolises the “Free World”—and has a moral duty to protect the freedoms of Hongkongers—does not tell the whole story. Conspicuously absent in this framing is a reflection upon how British colonialism shaped the institutions and structures of Hong Kong to limit Hongkongers’ political horizons, something that continues to harm us today.

Britain’s most recent betrayal reinforces the truth: Hongkongers should neither count on or accept the United Kingdom’s performative “solidarity”. What we need is for our allies in Britain—students, workers, activists and diasporas—to critically confront the history of Hong Kong’s colonisation, and recognise that liberation for Hong Kong must come on our own terms: we will have no liberation without decolonisation.

Myths of our colonial past

Mainstream British media often describes Hong Kong’s current plight as an erosion of freedoms and eradication of rights. This view is expounded by Ben Rogers, deputy chairman of the Conservative Party Human Rights Commission, founder of the NGO Hong Kong Watch and an outspoken member on Hong Kong in British public life. Rogers called Hong Kong “a city that had all the freedoms that we enjoy” that has been “increasingly threatened over the last 5 or 10 years.” A white British journalist I interviewed during a solidarity rally in London even said Britain should support Hongkongers’ struggle because the “liberties and parliamentary system we cherish here in the West that we have given to Hong Kong” are now “taken away by totalitarian China.”

But how can there be an “erosion of rights and freedoms” if we never actually had them? In the early decades of Hong Kong’s colonisation, policies explicitly prevented Han Chinese subjects from going out at night or holding public assemblies without a permit. For the overwhelming remainder of British rule, Hongkongers could not be elected to the government, while their efforts to strike and protest were repeatedly suppressed. The city’s governors were appointed by the British monarch, while white Britons held all high-level roles in government until their final years in territory, when they promoted big business-friendly local elites into those positions.

Most Hongkongers enjoyed no political representation until the 1950s, when elected seats were introduced to the Urban Council under pressure from the Chinese community. But this was a sham democracy—there were far fewer elected seats than appointed members, while the Council itself was merely consultative and had no decision-making power. Further reforms would not take place until 1985, when Governor Edward Youde introduced “functional constituencies”: seats in the Legislative Council (Legco) that would be directly chosen by Hong Kong’s sectoral interests.

Workers are excluded from important functional constituencies, all but guaranteeing the boss class control of Hong Kong’s lawmaking body and budgetary decisions.

This, too, was a farce: the majority of the functional constituency seats were selected by corporate interest blocs. This allowed the British administration to co-opt local elites while creating an appearance of democracy. Even now, only large corporations and employers can vote in important constituencies like insurance, finance, real estate and construction, import and export, transport, catering, and wholesale and retail. Workers and other stakeholders are excluded from these constituencies, all but guaranteeing the boss class control of Hong Kong’s lawmaking body and budgetary decisions.

Calls to open up all Legco seats for universal suffrage—today a central demand of mass movements in Hong Kong—were actually first thwarted in 1994 by the administration of Chris Patten, the city’s final colonial governor. Patten’s Secretary of Constitutional Affairs argued it would contravene the Basic Law as well as Beijing’s position on the issue, the same excuse given by CY Leung’s administration two decades later.

Nonetheless, British colonialism is often remembered fondly for reforms implemented by Governor Murray MacLehose’ administration in the 1970s, including the building of public housing, provision of free basic education and public healthcare, and the establishment of the Labour Department to better protect worker rights. It is not inaccurate to suggest these reforms contributed to Hong Kong’s economic well-being and material abundance, but one must not forget these changes only came on the back of sustained anti-colonial movements in the 60s that posed an existential threat to British rule.

If So Sau-chung had not begun a hunger strike to block the rise of ferry fares and the prices of other public utilities in 1966, the British administration would not have realised people’s dissatisfaction with their living conditions was already critical. At the time, many workers were earning poverty wages, often overworked and poorly protected by the law, while tens of thousands of people still lived in unsafe shanty homes due to inadequate affordable housing.

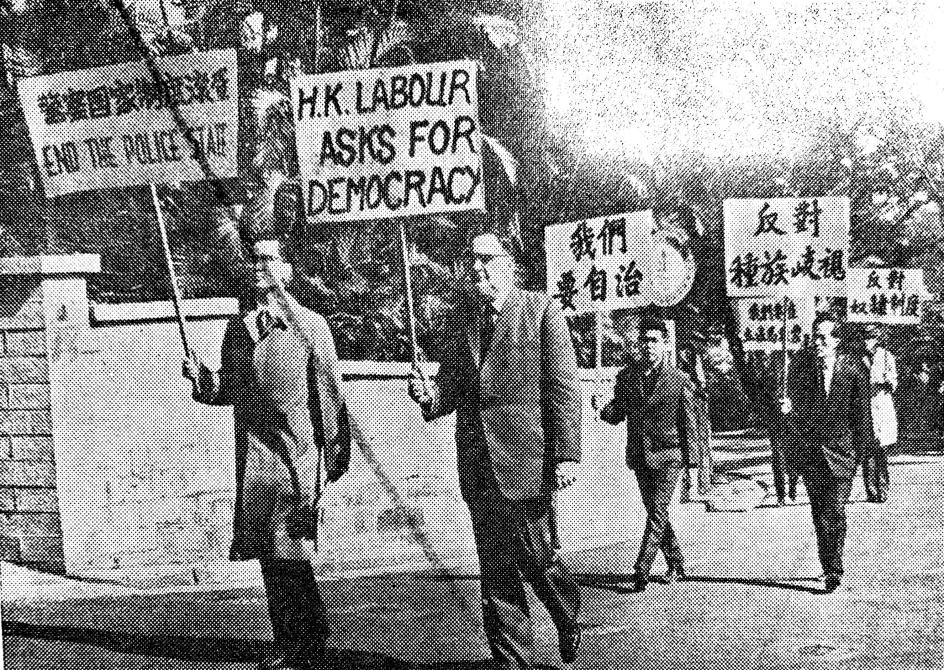

This was soon followed by the 1967 riots during which several large-scale labour disputes were taken up by leftist groups—inspired by the Cultural Revolution ongoing in Mainland China—as an opportunity to mobilise anti-colonial resistance, culminating in a months-long militant attempt to overthrow the regime. It was only suppressed when the colonial administration enacted the Public Order Ordinance, deploying the military and granting police wide powers to arrest. The Ordinance was amended in 1970 to raise the maximum prison term for rioting from two to ten years, now faced by hundreds of protesters for their participation in the current movement.

These resistance movements severely undermined the legitimacy of colonial rule, but rather than devolving power to ordinary folks, Britain opted in 1975 to establish a public opinion monitoring system called Movement of Opinion Direction, which produced weekly reports for high-ranking colonial bureaucrats to identify potential threats to the colonial state. The operation was hidden from the public and was designed for “an alien state to retain legitimacy without introducing an electoral system,” according to researcher Florence Mok.

Later-uncovered secret telegrams between MacLehose and Westminster officials reveal the governor implemented reforms because “not only must legitimate demands be satisfied, but the population must be convinced that such satisfaction is genuinely the objective of the government.” MacLehose also noted the colonial administration must implement policies that can prolong China’s confidence in British rule so that “a favourable negotiation would be possible.”

This insight into Britain’s colonial statecraft shows Britain never cared for the political agency or material interests of Hongkongers—otherwise it would not have waited until popular discontent was boiling over and the handover date was looming to implement political and social reforms. Read against this history, it is clear Britain’s concern for our city today is similarly empty and does more to obscure the harm of British rule in Hong Kong than anything else. For Britons, solidarity with Hong Kong must thus begin from a different premise: one that recognises the current movement as a struggle to make space for democratic futures beyond not only Beijing’s authoritarianism, but also the constricting frameworks prescribed by colonial governance.

The forgotten economics of the Sino-British Joint Declaration

Many Hongkongers have called for Britain to help pressure Beijing to uphold the Sino-British Joint Declaration—which establishes the principle of Hong Kong’s semi-autonomous status under the policy of “One Country, Two Systems.” Suggested measures include granting Hongkongers British residency and imposing sanctions on Hong Kong and China.

Unfortunately, the Joint Declaration hardly holds the key to our liberation. Of course, it is well-known that “One Country, Two Systems” lays forth protections around Hong Kong’s judicial independence and political freedoms. But what is less-often remembered is the Declaration’s other main purpose: to maintain the city’s exploitative neoliberal socio-economic institutions.

The Declaration offers painstaking details on the economic arrangement of Hong Kong post-1997: explicitly safeguarding private property, free trade, the free flow of capital, the financial markets, and “mutually beneficial economic relations with the United Kingdom and other countries, whose economic interests in Hong Kong will be given due regard.”

These processes have enriched foreign businesses and their partners and financial intermediaries in Hong Kong, at the expense of low-paid, casualised workers.

But this arrangement serves the interests of British businesses and Hong Kong’s elite far more than it does ordinary Hongkongers. Hong Kong has become a regional hub for multinationals in organising value chains and outsourced production, providing the geographic proximity, low-tax environment, and financial infrastructure needed to exploit “business opportunities” (read: poorly protected cheap labour and low environmental standards). These processes have enriched foreign businesses and their partners and financial intermediaries in Hong Kong at the expense of their low-paid, casualised workers in mainland China and Southeast Asia — while also pushing many Hongkongers into precarity as the city “upgraded” to a knowledge-based economy without the necessary welfare provisions to smooth the transition.

The Joint Declaration had set Hong Kong’s economy onto the path of financialisation. Hongkongers were borrowing 50% more than they were earning in the lead up to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis that burst the housing bubble. (In 2018, this figure approached 120%, the highest in the world.) Such was Hong Kong’s reliance on finance and real estate that Hong Kong’s first Chief Executive, Tung Chee-hwa, abandoned a plan to build 85,000 public housing units after pressure from property and financial interests following the crisis. Instead, his administration focused on stabilising the housing market by strictly limiting land auctions, ceasing an important home-ownership subsidy and relaxing tenancy controls.

The decision to bail out real estate developers after the housing bubble burst was praised at the time for saving many property owners from losing money. But with house prices catching up with pre-crisis levels within the decade and skyrocketing ever since, the number of residents in squalid subdivided flats rising and home-ownership becoming unaffordable even for the middle-class, many are left to rue the path that our policymakers have taken.

In fact, this pro-business land policy is integral to Hong Kong’s economic model. To attract foreign capital and maintain the commitment to frictionless trade, the Hong Kong government levies few taxes. It makes up for this fiscal conservatism by relying on land auctions for revenue. This means the government restricts the land supply to keep prices high, which has resulted in a real estate oligopoly most interested in erecting lavish residential complexes catered to a wealthy clientele. While the property magnates rake in profits, the commodification of land has turned Hong Kong into one of the world’s least affordable cities to live in.

Hong Kong’s financialisation has become even more thorough in the last two decades, with the IPO of the MTR Corporation (the major property developer that runs Hong Kong’s railway systems) and Link REIT (set up to run the retail facilities of public housing estates, for-profit). Meanwhile, our pensions are entrusted to fund managers that charge administration fees so high people often end up losing money. Financialisation means Hong Kong’s firms prioritise paying dividends to their shareholders, pushing them to ruthlessly reduce costs, creating a more casualised labour market, trapping low-skilled and less-educated workers between low-wage jobs and nonstandard employment.

The ossification of class disparities, increased living expenses for ordinary people, gentrified neighbourhoods and widespread precarity that has developed over the past 23 years are a direct result of the laissez-faire policy approach that our government has implemented, as prescribed by the Joint Declaration: when faced with the choice of citizens’ or corporations’ interests, it has repeatedly taken the side of capital.

Self-determination means more than the right to vote

Every fifth person in Hong Kong lives in poverty. Yet the idea that “economic development” and “improving competitiveness” are crucial for Hong Kong’s general well-being has been hardwired into our social consciousness. There is no doubt Hongkongers’ political freedoms should be defended against Beijing’s encroachment, but if this takes the form of upholding a finance-led regime of accumulation and exploitation, what good can it really do?

The problem with the most popular slogan from Hong Kong’s ongoing political uprising — “Restore Hong Kong, liberation of our times,” is that it suggests we can somehow return to a fairer past, when Hong Kong was supposedly a healthy society, observing the rule of law free from Beijing’s interference.

But this view is quite absurd. Even without any pressure from Beijing, our courts have prosecuted waste pickers for obstructing public spaces, while turning a closed eye to corrupt politicians. Workers making claims against their employers for workplace injuries have no access to legal aid, but when they try to comb through complex legal procedures on their own, they are chastised for wasting the court’s time. Our prized courts have done nothing to stop the IPO of Link REIT, the demolition of Queen’s Pier, or the government’s decision to deny residency rights to Mainland-born children of Hong Kong parents and migrant domestic workers. The rule of law that many scrambled to protect as the bedrock of a fair and prosperous Hong Kong has been little more than a barrier to justice for poor and marginalised communities.

It is heartening, then, that progressives are finding the space to push anti-capitalist politics and incorporate class-based demands within Hong Kong’s movement, from the recent wave of new trade union registrations, actions to recover wage arrears, to repeated attempts to organise a general strike in recent months. Beyond just electoral democracy, these politics are about building a society that affords us real control over our lives, free from the dictates of the state and capital. They envisage equitable distribution, the breaking-up of vested corporate interests, well-funded public services, workplace protections, accountable policymaking and community relationships based on mutual aid and care.

Along with these efforts, our movement must reassess its requests for solidarity from governments like the United Kingdom’s. It does not help Hongkongers when Britain decries political repression but upholds a system responsible for so much economic misery. It is naive to think that the British ruling class—which benefits the most from unfettered global markets and neoliberal social policies—would ever help Hongkongers achieve true self-determination.

Recently, an editorial in British tabloid The Sun suggested Britain should create a new visa category for “the best and brightest” of Hongkongers, to offer an “ambitious generation the chance to work” in the country. But “not all Hongkongers should be waved through,” it warned: Hongkongers should only be allowed in if it would produce “a huge boost to the UK economy”. Just as insultingly, Britain has not offered political asylum to Simon Cheng, the UK consulate worker recently detained and tortured by Chinese authorities for his alleged role in the Hong Kong protests, instead dangling a two-year “working holiday” visa that leaves him no path to permanent residency. What fate awaits the migrants—Hongkongers or otherwise—who are not deemed good, bright and ambitious enough by the Home Office?

Last December, Home Secretary Priti Patel argued relaxing immigration controls for Hongkongers holding BNO passports “would be a big sign that Britain is not anti-migrant as we leave the EU, and that it would demonstrate the kind of country we want to be.” But to say Britain is “not anti-migrant” is an insult to those facing hostile environment policies, fishing raids from immigration enforcement, and retaliation for standing up against exploitation. It ignores Britain’s brutal indefinite detention and deportation of suspected “irregular” migrants. It is an affront to the 39 Vietnamese migrants found dead in a refrigerated trailer in Essex last October, killed not just by the cold, but the hostile borders that put them at the mercy of traffickers.

The Home Office’s effective rejection of Hongkongers’ political asylum claims only rubs salt in the wound. Its February 11 guidance note shied away from how Hong Kong’s government is weaponising colonial-era laws—the Emergency Regulations Ordinance and Public Order Ordinance—to repress the movement, stating that these laws provide “reasonable sentences for public order offences.” The note also overlooks arbitrary arrests, police mistreatment of protesters in pre-trial detention, and their regular and unaccountable use of excessive force during clashes with protesters, deeming these as merely “adverse attention from the authorities.”

To say Britain is ‘not anti-migrant’ is an affront to the 39 Vietnamese migrants found dead in a refrigerated trailer in Essex last October, killed not just by the cold, but the hostile borders that put them at the mercy of traffickers.

The British immigration system’s hostility to migrants is not only fundamental to the operations of its neoliberal economy. It also obscures the historical and ongoing role of British colonialism and neo-imperialism in creating many of the global inequalities that force people to migrate in the first place. If there is anyone Hongkongers should build solidarity with, it is these migrants and those who advocate for their rights, rather than the British state.

We must not let the British state whitewash its brutality by letting it bask in its performative solidarity with Hong Kong’s protesters. We must recognize how its policies, from its colonialism to today’s anti-migrant border controls, not only undermine Hongkongers but wholly discredit the myth of Britain as a bastion of freedom and humanism.

Those in Britain who are allied to our cause must also fight to dismantle Britain’s border regime with a fierce anti-racist, anti-classist politics. We urge you to struggle for an alternative Britain that opens its borders to all those who require asylum, not just Hongkongers holding BNO passports; that accords migrants the same fundamental rights as locals, from access to healthcare to parity in wages, benefits and working conditions; that regularises, not criminalises undocumented migrants, so that we never have another Essex 39. We hope that by reckoning with Britain’s history with our city and other victims of its imperial conquests, you will be inspired to get organized and join us in our revolution: against all the powers that dispossess and disenfranchise us.