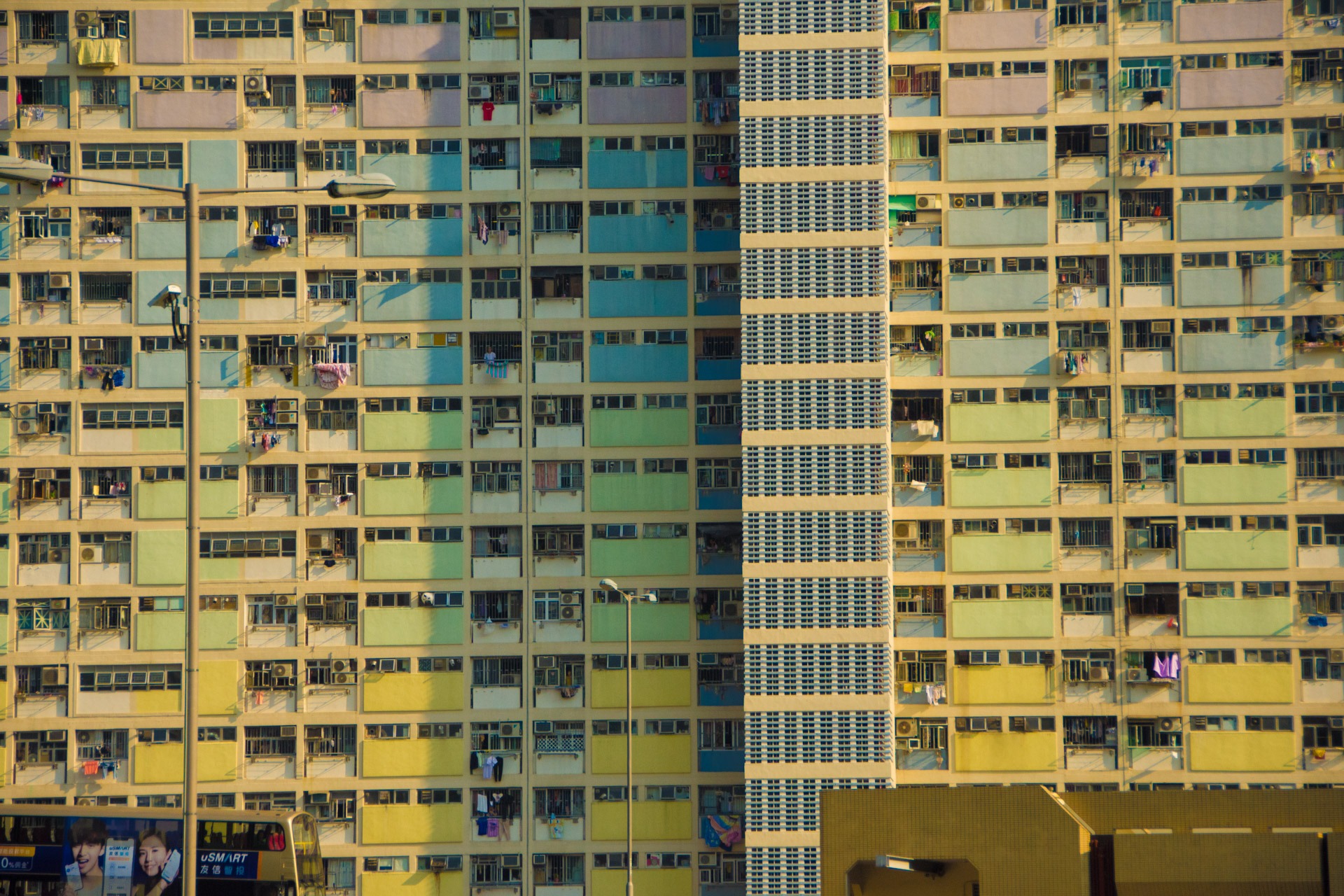

Unaffordable rents, while not explicitly addressed by the movement’s key demands, shape every facet of Hong Kong’s civic life. Nearly half of Hong Kong flats rent for upwards of HK$20,000 (US$2,550) a month, more than 70% of median household income—making it the world’s costliest housing market. Even with the availability of underutilized land, the government has failed to build more public housing or reduce rents. This is partially due to Hong Kong’s residual colonial institutions, where authorities tasked with land reacquisition and planning also act as land developers and land premium negotiators; they use taxpayer funding to finance private development without public consultation or oversight.

These labyrinthe semi-public statutory authorities, such as the Urban Renewal Authority (URA), MTR Corporation, and Link Real Estate Investment Trust (Link REIT), are motivated by profit from land premium rather than the public good. For instance, the MTR has increased transit fares disproportionate to the cost of living; Link REIT, the largest real estate investment trust by market capitalization in Asia, has been known to dramatically increase rents and management fees. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) government’s dependence on land premiums for revenue has led to nonchalance: on the issue of high transit fares, Chief Executive Carrie Lam remarked publicly in 2017 that “there is really nothing [she] can do.”

For decades, Alice Poon witnessed the tactics of Hong Kong property developers first-hand, especially as a personal assistant of Kwok Tak-seng, the late co-founder of Hong Kong’s largest conglomerate, Sun Hung Kai Properties. Picking up Henry George’s 1880 classic Progress and Poverty between work, Poon realized that its critique of landowners extracting unearned increment from their communities formed a familiar image of her former industry, and felt the need to research “out of a sense of justice.”

The result of her research, Land and the Ruling Class in Hong Kong, is a lucid history of how six families took advantage of land supply restrictions in the Sino-British Joint Declaration to form a collusive monopoly on Hong Kong’s land. Initially self-published in 2005, the book’s Chinese translation became a bestseller, cemented “real estate hegemony” (地產霸權) in the public discourse, and became a touchstone for the land justice movement.

We interviewed the author to discuss the role of land monopoly in the tumult of the current protests.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Brian Ng: Your 2011 book, Land and the Ruling Class in Hong Kong, popularized the concept of real estate hegemony (地產霸權) in the city’s political discourse. You argue that historical land supply ceilings, alongside collusive legislation that benefits incumbent monopolies and real estate developers, have consolidated wealth and influence in the hands of a few dynastic property moguls. How has the city’s real estate hegemony changed, or not changed, since then?

Alice Poon: As much as the Chinese version of my book was a huge bestseller and a hot discussion topic in Hong Kong in the couple of years following its 2010 release, the successive HKSAR governments have done practically nothing to remedy the fundamental flaws in the land and tax systems which have always been skewed in favor of the wealthy landed class. All they could manage was a slight slap on the wrist through regulating, if belatedly, developers’ fraudulent sale practices. The Donald Tsang, C. Y. Leung, and Carrie Lam administrations have all adamantly refused to re-introduce residential rent control, a measure that had proven effective in keeping rents in check in the pre-handover days and should never have been retired in the first place.

As the HKSAR government is the largest land supplier and it relies on land revenue as a key fiscal income source, it follows that it is as much invested as the big developers in the high land price policy, which has worked over decades to spike consumer prices and widen the wealth gap at the expense of the unpropertied class in society. This is the Gordian knot in Hong Kong’s land and housing issue.

Worse, all land income, instead of being channeled in an equalizing effort to areas like public housing, education, medical care, seniors’ welfare, and so on, is put in the Capital Works Reserve Fund which is earmarked for financing new, often unnecessary, infrastructure. Such expenditure then translates into a land value booster—that is, a subsidy for the land-rich developers, and more land receipts for the government. And the government itself is a major player in the property market through its real estate arm, the MTR Corporation. The land and tax systems have bred injustices that go in a vicious spiral.

BN: The violent clashes in Yuen Long on July 21, 2019 drew attention to the collusion between real estate developers that derive profit from indigenous land and the Hong Kong legislative bodies that write landlord-friendly policy. Can you talk about the outsized influence of the New Territories gentry—led by the Heung Yee Kuk governing body—in legislative politics and the role of the Small House Policy in land sales?

AP: The Small House Policy combined with the defunct Letter B system, have a long history of spurring land dealings between New Territories landowners and the big developers, which enhances the latter’s land hoarding process in the New Territories. Anyone with a sense of right and wrong can see that the Small House Policy is grossly unfair—why should New Territories–born males perpetually enjoy this special housing privilege that is denied to all other Hong Kongers? My impression is that, right from the handover, Beijing has been relying on this group for political support. Probably the patriarchal village leaders did a good job groveling to the similarly patriarchal new master. So it was not surprising to see it gain a firm foothold in the legislature with Beijing’s tacit approval.

Rent control should form a crucial part of any socially-conscious housing policy, especially in Hong Kong where land supply is controlled by government and the property oligarchs.

BN: How do you see the role of the MTR and transit networks in the Hong Kong protests? On one hand, the MTR has begun cooperating with police to prevent mass assemblies, shut off protesters’ escape routes, and detain protesters within stations. Yet mass transit has also been essential to the city’s urbanism, and surprisingly important to protest strategy. In early discussions of a general strike, Chan Tak Wan proposed a strike fund aimed at organizing mass transit workers, and protests in early September leveraged disruptions to airport traffic for visibility. How can grassroots political movements draw further leverage from transit?

AP: It is clear that the MTR has been acting in concert with the Hong Kong police on behalf of the tone-deaf and obtuse Carrie Lam administration. The intention of the random shut-down of stations is clearly to enrage MTR riders and let protesters take all the blame. Vandalism targeted at public transit facilities may not be an effective protest tactic as it would alienate ordinary citizens and make the movement lose some support. Peaceful strikes would seem a better alternative. But Carrie Lam’s face mask law has put things into flux and is likely to backfire.

BN: The idea of “real estate hegemony” captivated a post-80s generation unable to rent housing and attain financial independence. The current anti-extradition protests, no doubt driven by similar pressures such as rising rents, are more urgently targeted towards Beijing than the oligarchs (inasmuch as their interests are entangled). What demands should we be making for economic equality and land policy reform? How should we research and critique the role of public corporations with land ownership like Link REIT?

AP: This indeed is the million-dollar question. As I mentioned above, the devil is in the land and tax systems.

In terms of land and tax policy reform, a fairer tax system is one that serves a redistribution function. For starters, if property owners are actual payers of the land premium—Hong Kong’s so-called hidden tax—the moment they purchase units from developers, would it not be more socially just for government to spend this revenue for the benefit of society as a whole, rather than to recycle it back through infrastructure spending into developers’ pockets as land value increment? Why not let developers bear the cost of infrastructure directly when they develop a piece of land? It is crucial for government and society to get rid of the high land price mentality. Instead of relying on land receipts for its fiscal health, and with a view to redressing the ever-widening wealth gap, government should explore other possible tax sources, such as a dividend tax, capital gains tax, estate duty, or a wealth tax.

Rent control should form a crucial part of any socially-conscious housing policy, especially in Hong Kong where land supply is controlled by government and the property oligarchs. Renting should always remain a viable alternative to purchasing, if young people are ever going to be able to afford a piece of roof above their heads and at the same time retain some kind of financial independence. Along with the provision of public housing for low-income Hong Kongers, residential rents should be made affordable through imposing restrictions including rental price caps or a rent freeze. These could be put into place immediately.

It all comes down to the feeling of desperation among young people about their bleak future, combined with society’s disillusionment with Beijing who blatantly reneged on the promise of universal suffrage enshrined in the Basic Law. If universal suffrage were attained, it would mean every citizen would have a genuine political say in government policies that affect his or her livelihood, and this is basically what protesters are striving for.