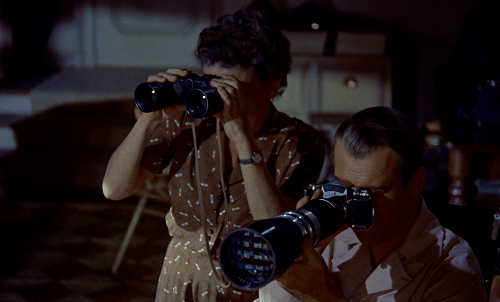

As geopolitical tensions continue to rise between the United States and an economically ascendant China, much of the knowledge production, public discourse, and media coverage continues to be mediated through the normative model of the “China watcher.” This term—the origins of which can be traced to white Westerners hired by colonial governments to monitor and report back on Chinese people, cultures, and institutions—continues a legacy of Orientalism through a white male gaze that shapes understanding of not only China, but also systematically excludes Black people, experiences, histories, and ways of knowing from mainstream discourse.

As a response to these exclusions, Columbia J.D. candidate Kori Cooper founded Black Voices on Greater China, an open source directory of work by Black practitioners, artists, and scholars focused on Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Taiwan.

Kori spoke with Lausan members on her motivations to intervene in the continued Orientalism that pervades China studies, the complicated history between Black liberation struggles and Chinese political leadership, the danger of leaning into proximity to whiteness as a method for achieving political aims, and the Chinese government’s strategic use of self-Orientalization as a logic for consolidating control domestically and avoiding scrutiny internationally.

Lausan Collective: Can you summarize your recent paper in Columbia Law Review, which argues that historically white American institutions (specifically American law schools) that study China need to address the exclusion of Black scholars and voices? What prompted you to write this particular critique?

Kori Cooper: My experiences working in the field of China studies prompted me to write my critique. These experiences built up over time and led me to realize that a direct analysis of the practices and conversations American institutions in particular are hosting about China, and the world, is necessary. Examining this subject within the context of US law schools was particularly of interest to me because these institutions are influential and often construed to be the centers of knowledge production in the world—an assumption that tends to overlook the contributions of Chinese, African, and many other academic institutions.

The majority of the leading academic institutions in the US are historically white, and thus the exclusion of Black voices and perspectives from elite spaces has become routine. In all the years I have attended events which focus on China’s relationship with the rest of the world, with titles like “China in Africa,” “China-US Relations,” or “China and the Middle East,” I have rarely seen anyone who identifies as Black participate as a panelist. I have also seldom seen any person who is dark-skinned in this role. Over and over again, I have witnessed a panel made up entirely of male, white and Chinese scholars get together to talk about what “Americans” think about the US trade relationship with China or what is best for Africans, without ever including Black scholars.

Black people have a stake in China’s relations with the rest of the world. Recent developments, such as incidents of legalized discrimination against Black expatriates, tourists, and students in China demonstrate this point. Many Black scholars, such as Keisha A. Brown, Robeson Taj Frazier, and many others I cite in my paper, could weigh in on such topics. But you would never know that based on the events I have mentioned.

As I suggest in my article, this state of affairs has created a gap in the field of study that causes schools to overlook unique ideas and views that come from individuals who do not fit into the traditional model of the Chinese national or so-called “China expert.” To change that paradigm, I thought it would be helpful to put down on paper a kind of manifesto that others can learn from and refer back to, assuming they believe racism is wrong. In summary, I argued that US law schools should actively promote inclusion within Chinese legal studies programs to improve their academic quality, as well as their value to all members of the legal community, and suggested ways in which they can do so.

LC: What aspects of the political and economic histories of China and Africa—and Chinese people and Black people more broadly—demand space for Black scholars to study China on their own terms? Are there good examples of these interactions between Black and Chinese voices and epistemologies?

KC: There are numerous examples of important interactions. For instance, during the Maoist period, African-American activists like W.E.B. and Shirley Graham Du Bois believed that Chinese political leaders would play a central role in assisting Black people in our struggle against US imperialism. For that reason, the married couple traveled to China to meet with Mao Zedong. There was also Maoist propaganda that depict Black people as allies in overturning global Western hegemony. Indeed, while those of the African and Asian diasporas are often thought of as occupying entirely separate cultural and political positions, history paints a much more nuanced and complex picture, with periods of inter-connectedness interspersed with tension between the two groups.

LC: Why does Orientalism remain a problem in Chinese studies and area studies in general? Why is there so much resistance in these schools of inquiry when challenged to move away from the mediation of the white gaze?

KC: The answer is best articulated by postcolonial studies scholar Edward W. Said in his seminal work Orientalism: “Once we begin to think of Orientalism as a kind of Western projection onto and will to govern over the Orient, we will encounter few surprises.” Indeed, the terms used to describe those working in the field today, such as “China watcher,” “China hand,” and “China expert,” were originally used to describe white Westerners who had been engaged by the military or government to monitor China and Chinese people. They were obliged to report back with information that might prove to be useful.

There is strong resistance to the idea that schools of inquiry, including not only Chinese studies but really almost every other field, such as that of English and legal studies, should move away from the mediation of the white male gaze because modern Orientalism is embedded in Western culture. It sometimes comes to us in seductive packages. For example, stereotypes like that of the lazy, ignorant, and untrustworthy Black person are taught by way of popular television, movies like Birth of a Nation, books, and so-called “objective” reporting. People become indoctrinated in an Orientalist worldview from an early age.

From the Orientalists’ perspective, everything the subject does becomes the object of suspicion. Misogynoir, and anti-Blackness more broadly, must be understood as a kind of Orientalism. China studies is seen not to have a problem with Orientalism because it is often viewed as an objective field of study; you hear people say that one either understands how “China works” or they don’t. But this idea of objectivity is shaky. One might recall the much-discussed “controversy” the American media reported on in August 2012, after the world-famous tennis player Serena Williams performed a brief celebratory dance upon winning a match. One journalist said, “And there was Serena… Crip-Walking all over the most lily-white place in the world… You couldn’t help but shake your head.” Another called her joyous celebration “akin to cracking a tasteless, X-rated joke inside a church… immature and classless.” In their excessive focus on the male outrage that arose at Serena’s win, journalists demonstrated that misogynoir can very much taint their reporting, a practice many understand to be objective.

It may be confusing to realize that there are non-white Orientalists as well as white ones, but as the Black anti-colonial thinker Franz Fanon put it, “Imperialism leaves behind germs of rot which we must clinically detect and remove from our land but from our minds as well.” In other words, just as there are people in these fields who are known as virulent racists, there are others from across the cultural and political spectrum whose minds have been colonized and are therefore unaware of the ways in which Orientalism continues to shape their thinking. Careers and privileges enjoyed by many are also predicated on making sure the way academia works stays the same. Here, Orientalism remains uninterrogated and continues to plague academé in these areas.

Why does the imagined audience of so much scholarship about China continue to be white and male?

LC: Said’s study of Orientalism was of course made in the context of the Middle East. Does that complicate the application of his concepts to China, where there are different histories of colonization and different political and economic interests? Is there a way that Orientalism can act as a lens through which we can see the common threads between Islamophobia, Sinophobia, and anti-Blackness globally?

KC: Said’s study did mainly focus on the treatment of the Middle East and the Muslim world, but he also names Sinology, philology, and other fields that have tended to exoticize that which is traditionally foreign to European culture. His concepts can be applied to analyzing how the US/Americans and Europeans have studied China, despite the different histories and interests involved.

Said makes clear that the very notion of “the Orient” alludes to Islamophobic, Sinophobic, and anti-Black sentiments. These sentiments have become entrenched because of over-generalizations as well as exploitative practices and actors in the fields I’ve mentioned. Postcolonial theory influenced by Said’s work in Orientalism reveals the global continuities between Islamophobia, Sinophobia, and anti-Blackness: The problem of Orientalism is not only one of making sweeping generalizations but also of making work motivated by a desire to establish white racial superiority seem objective, of distorting and flattening geography, people, and culture, of silencing the subject, and of making the white Western observer “a hero rescuing the Orient from the obscurity, alienation, and strangeness which he himself had properly distinguished.” These forms of racism interrelate with each other. And these prejudices play out in non-white contexts as well. For instance, China’s targeted discriminatory treatment of Uyghurs—a Muslim ethnic group—among other indigenous and ethnic minority groups in the region is Islamophobic, while frequent incidents of legalized discrimination against Black expatriates, tourists, and students point to anti-Black prejudices across the country.

LC: How do these Orientalist norms structure which voices and discourses are “heard” and which are dismissed in China studies? Are there some examples of discourses that are dismissed, erased, or muted in that they do not speak at registers cognizable to norms of the field?

KC: In her well-known book chapter “Can the Subaltern Speak?”, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak notes that often “the subaltern,” the oppressed party, makes an attempt at self-representation or perhaps a representation that falls outside “the lines laid down by the official institutional structures of representation.” Journalist and cultural anthropologist Ann Marie Baldonado explains, “Yet, this act of representation is not heard because it is not recognized by the listener, perhaps because it does not fit in with what is expected of the representation.” Thus, representation by subaltern individuals can seem nearly impossible. However, Baldonado continues, “Many artists, activists, and thinkers who are committed to critical political and cultural resistance still work to challenge status quo representation and the ideological work it does, despite the structural failure of such subaltern speech.”

In relation, whenever I think a concern or the point a critic is trying to make should be apparent, but is not, I think of Chinua Achebe’s article, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness.’” His critique of the 19th-century classic Heart of Darkness made waves in the realm of literary studies, but to me, his problem with the novel is not difficult to understand. He says, “Can nobody see the preposterous and perverse arrogance in thus reducing Africa to the role of props for the break-up of one petty European mind? But that is not even the point. The real question is the dehumanization of Africa and Africans which this age-long attitude has fostered and continues to foster in the world.” Achebe concluded that while there is plenty to admire in the novel, and Conrad certainly had a specific stylistic talent, it is past time scholars acknowledge Conrad’s racism as well. Unsurprisingly perhaps, his critique was not universally well-received when it was originally published in the late 1970s. Nevertheless, Achebe empowered successive generations of scholars to think not just in terms of how not to be overtly racist themselves, but to be antiracist—to think critically about racism and colonialism as structures that must be undone and unlearnt.

“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus side-shows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.”

– “Untitled: Four Etchings,” Glenn Ligon

LC: If Said’s critique forces us to examine the power relations inherent in knowledge production, in what ways do Black/Africana perspectives disrupt the dominant racial-colonial mode of knowledge production?

KC: Black/Africana activists, professionals, and artists have made powerful interventions in discussions on politics, culture, and history. Some of these interventions are lesser-known than others. For instance, in 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States (1948), Richard Wright, the author best known for the novel Native Son, described the lives of those millions of Black US Americans who were forced to flee the south under threat of genocide and persecution, as well as the lives of other Black people living in the US. Most US Americans are taught in school that Black people left the south, beginning in the early 20th century, seeking jobs and better wages in the north. The reality is much darker. What is typically referred to as “the Great Migration,” having taken place over a period of several decades, was a period during which Black citizens tried to escape plagues of legalized lynchings, segregation, rape, burned black churches, burned black towns, systematically forced sterilization, forced labor, and other racialized atrocities. These abuses took place in northern cities like Chicago, where I was born, as well as in southern states, but occurred at the highest frequency in the deep south. Wright himself had to leave the south.

These individuals who fled—from whom I am descended—were, in fact, refugees, not unlike Rohingya escaping Myanmar or Uyghurs fleeing Xinjiang province. However, they are still not widely recognized as such. This is likely related to the fact that international human rights law claims that those considered “refugees” must receive protection and aid—even if this is practically not always what happens. Instead, Black refugees are often criticized as “economic migrants” and locked out of governmental support. In this way, even seemingly neutral concepts such as “migration” and “refugee” are prefigured in certain ways by the academy to include as well as exclude, with implications for power relations, inequality, and oppression. Early interventions in academic and popular discourse, like that staged by Richard Wright, have done much to preserve the true story of what Black citizens have endured. No one who writes or discusses US history, culture, or politics should neglect to mention this period of history and its continued legacy.

LC: In what ways do the Black Other and the Chinese Other have common stakes in critically interrogating this white Western epistemology? Are there any points of tension or contradiction that must be addressed in moving towards a collective and liberatory form of knowledge production?

KC: There are useful observations, ideas, and styles of expression that can be stripped out from work whose authors likely never imagined these two groups as part of their primary audience. Rather than seeing ourselves as parts of different struggles, we should see ourselves as all united in a singular struggle: against authoritarianism, police violence, brutality, and the systems that produce it. And our collective discontent is what will enable us to unite and overthrow these systems eventually. I thought of this when, in his last visit to Columbia Law School, Hong Kong pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong talked about how the movement he describes as “our summer of discontent” began with the Umbrella Revolution, adapting the first two lines of William Shakespeare’s Richard III: “Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this sun of York.”

The points of tension or contradiction here, however, involve over-reliance on proximity to Whiteness as a method of achieving our goals. White supremacists have linked political and financial support for specific groups to receiving help in maintaining Black oppression. No one wants to be at the bottom of the hierarchy, so it commonly becomes the case that activists of other movements, whether in the US or beyond, will set aside Black allies to gain White ones, who may appear more powerful and influential. To Hong Kong activists who have endorsed right-wing US politicians and disparaged the Black Lives Matter movement, it is my sincere wish that you acknowledge our shared struggle. We all must stand firmly on the side of equality and oppose policing, wherever it may be. As the artist, academic, and activist Lilla Watson once said, “If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

LC: Is it enough that we call for greater diversity and inclusion in China studies so that more Black scholars are able to study China? Given academia’s capacity to co-opt potentially subversive voices, how do we go further to initiate real structural and epistemological changes?

KC: As a general rule, I do not think programs and conferences about China and the world should be organized without the involvement of people from various cultural and ethnic groups. Not only does the quality of China studies programs suffer from the lack of diversity and inclusion, but exclusionary cultures help further entrench existing inequalities in academic spaces and elsewhere.

But greater diversity and inclusion in China studies is merely a starting point, not a solution in itself. Achieving the political and economic enfranchisement of people of color is another crucial step. In addition, as I have mentioned already, to initiate fundamental structural and epistemological changes, allies must listen to what scholars of color have to say about their experience in the field and offer their genuine support toward improving everyone’s quality of life. For instance, Chinese nationals that come to the US to study should not be vilified as they have been under the Trump administration. In this instance, it was heartening to see major institutions firmly state their willingness to support Chinese students studying in the US.

Overall, the onus cannot be on minority groups alone to advance change. That is an enormous burden to carry. White scholars must hold themselves accountable for the choices they make. I often cannot help but notice that white support for universal equity and equal rights comes and goes. It seems that respect for human rights is treated like a fad or a trend, and I believe it must have greater significance than that. Those who have only recently begun to decry anti-Blackness in the field of China studies and beyond should be aware that real courage in action involves being willing to say what is true when the truth is unpopular. Black people have been telling the truth about racism and police brutality for centuries, only to be gaslit, punished, and dismissed. It should not take viral videos of extraordinary violence and harassment being enacted against us to change minds.

It is incumbent on white scholars to have conversations amongst themselves about how to morally and ethically advance their various practices, rather than ask Black people and members of other marginalized groups to volunteer a more significant amount of time, energy, and space, to instruct them on what racism in its various forms looks like. This is not to say that there should not be cross-cultural dialogue around these issues, but one must be mindful of how those interactions may impact the mental and physical well-being of others and consider ways to compensate and empower traditionally marginalized people in those exchanges adequately.

Do not, for example, impersonate Black and Brown scholars. Doing that limits the number of opportunities actual scholars of color have to advance their work. It is incredible that this needs to be said, but the stories of Natasha Bannan, Rachel Dolezal, Jessica Krug, and other white people who have come to prominence through their impersonation of Latina and Black women sadly speak to the necessity that I do so.

What would be more productive for white scholars is for them to educate themselves on the gaps in their knowledge of social and systemic inequality and push their institutions to hire more scholars from diverse backgrounds and allocate funding and space to initiatives led by scholars of color. Scholars from different marginalized contexts can and should unite to engage in a more politically-engaged and solidaristic practice of knowledge production that prioritizes horizontality and mutuality rather than extraction.

LC: Some may read your critiques as limited to US law schools or certain narrow segments of academia. What are the on-the-ground consequences of not challenging the dominant normative conceptions of the “China Watcher” or “China Expert”?

KC: The normative conceptions of the terms “China watcher,” “China hand,” and “China expert” have troubling implications: Who is doing the watching and what are they watching for? In discussing how European Orientalists pursued their subject of inquiry, Said observes that, “The Orient is watched, since it’s almost (but never quite) offensive behavior issues out of a reservoir of infinite peculiarity; the European, whose sensibility tours the Orient, is a watcher, never involved, always detached, always ready for new examples of what the Description de L’Egypte called ‘bizarre jouissance.’”

Eric Setzekorn, a scholar of Chinese history, demonstrates in the paper “The First China Watchers: British Intelligence Officers in China, 1878-1900,” that the origin of “China watching,” which was coined by analogy to birdwatching and which takes place from a distance, has its specific roots and habits in British colonial relations with China, particularly concerning military and intelligence priorities. The term “China hand” was used to refer to US American diplomats, journalists, and soldiers for similar reasons.

Today, Chinese nationals are rarely referred to as China experts, hands, or watchers. Knowledge produced by Chinese scholars is often seen as politically compromised because of a mix of Sinophobia and suspicion about the extent to which critical inquiry is possible under an authoritarian state or simply as inferior because it is produced outside the Western academy. This has broad implications for Chinese national students, many of whom go abroad to study in order to be taken seriously as academics, especially in light of recent US clampdowns on Chinese student visas.

Although the term “China expert” is most often used by media outlets to refer to foreigners who actively study China or have a deep familiarity with some aspect of the country through their work, they really ought to include further qualification when used, if ever. People should know if they are speaking to a Chinese art history expert, or a Chinese geography expert, or someone in another field of expertise. Scholars who can actually run the gamut are rare. We must challenge the idea that so many people can be referred to as an “expert” on an entire state and geographical area without qualification and that it is normatively appropriate to say that China studies programs are training “watchers,” lest we inadvertently adopt the type of lens traditionally used by colonial-era anthropologists (Orientalists).

LC: The history and continuing legacies of colonization are frequently invoked by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) through the “century of humiliation” discourse to justify many of their decisions in the modern-day. How would a scholar informed by critical race and decolonial theory offer a stronger, more nuanced critique than the predominant framework of liberal human rights?

KC: The CCP’s pushing of the narrative that “a hundred years of humiliation lives on in the mind of Chinese” as an explanation and justification for many decisions made today is happening in tandem with the enforcement of regulations that prohibit depictions of China as an active colonizing power in the media, either historically or speculatively. This is just one way in which the government engages in Orientalization of the self to avoid nuanced debate as to why it will not let Taiwan be independent or why it suppresses ethnic minorities in the Mainland. That is to say, the CCP is aware of Western stereotypes, such as the notion that Chinese people are rigid cyclical thinkers or the notion that they are physically weak, and sometimes play these stereotypes to their advantage. Unfortunately, many scholars accept this narrative of victimization and exceptionalism uncritically.

Actually, one of the limits of Orientalism is that Said does not explore the topic of self-Orientalization in-depth. Still, it seems apparent to me that self-Orientalization and the use of an exceptionalist discourse is a tool and instrument of consolidating control, not only domestically, but also internationally. Approaching what is happening with China politically from a Black existentialist angle would lead China scholars to confront how the maintenance of global hierarchies creates perverse incentives among nations.

As a Black scholar, I think of W.E.B Dubois’ concept of double-consciousness when considering this phenomenon. Those who have experienced racialized oppression and disenfranchisement in a society dominated by another group are always acutely aware of the ways others perceive them. Predicting the moods, actions, and responses of others becomes a honed skill because it helps ensure survival. One has a personal self and a public self, that is, in some ways, performative. The public self is performative in the sense that as the “Other” who is trying to gain access to something that is kept from you, you will sometimes act in a way that is unnatural in order to achieve that goal. For instance, a Black woman who wants to keep her job at a white company may tie back her hair (if it is densely curly) and act timid during get-togethers so that she is not perceived as a threat; studies have shown that Black women are often categorized as “threatening” and “too loud” by their white colleagues when they wear natural hair styles or demonstrate outgoing behavior.

The desire to put the Other on a pedestal when it is politically expedient stems from a colonial tradition.

History shows that China, like many other nations, has a history of imperialism. For instance, between 1644 and 1799, the Qing government had led an aggressive expansionist campaign that left a trail of blood and resentment in its wake. Among the notable cases of frontier incorporation was Sipsongpanna (Xishuangbanna), now known as an autonomous prefecture for Dai people in the extreme south of Yunnan Province, China, bordering both Myanmar and Laos. There was harsh enforcement of Qing cultural assimilation and hierarchy in order to make a clear delineation between those who openly resisted them and those who surrendered to their rule. Imperialist practices have not gone away. We see them in action today in the targeted discriminatory acts against China’s ethnic minorities, such as the mass internment, cultural oppression, and exploitation of Uyghurs.

Although the CCP often casts China as a once-powerful nation that is now full of people working in a hivemind fashion to reinstate its former glory, Chinese people are of course not such a monolith. The idea that there is a way of “understanding the Chinese mind,” as some have put it, is reductive. Other critical race and decolonial theorists might point out that much like the right-wing Republicans in US Congress who are drawing false comparisons between peaceful Black Lives Matter protests and the rioters who attacked the US Capitol on January 6th, 2021 to obfuscate the impact of white supremacy, the CCP has also drawn false comparisons between US Capitol rioters and the Hong Kong demonstrators in an attempt to mask its authoritarian agenda in the region.

LC: There is a subsection of scholars writing on China who, owing to their belief in a reified version of Third World solidarity, refuse to criticize the CCP’s economic and foreign policy decisions, such as China’s acquisition of strategic territory, military installations, and ports through the swapping of infrastructure project-related debt. How might the decolonization of China studies, both structurally and epistemologically, help us think through these dynamics?

KC: Tankies, as such people who embrace this mode of thought are often referred to, believe in an ahistorical ideology. As I have previously explained, decolonizing the field requires us to deconstruct and let go of both overtly degrading, as well as seemingly romantic myths and stereotypes, from the model minority myth and the myth of the noble savage to the portrayal of the magical Negro in popular media, and so on. Once this is done, it becomes possible to criticize the CCP’s policy decisions without distorting the motivations behind them or their significance. Indeed, the desire to put the Other on a pedestal when it is politically expedient stems from a colonial tradition of trying to tame and control non-white Christians, who Europeans deemed to be too threatening to interact with as equals, by setting up a hierarchy amongst their ranks. We must change this paradigm to accurately understand and realistically begin to solve the problems brought about by the CCP’s decisions.

LC: Decolonizing China studies would require not only combatting the normativity of whiteness but also patriarchy. What would China studies look like if Black feminism were an integral part of the curriculum and practice?

KC: It would look more attuned and responsive to the issues of today and the needs of society’s most vulnerable groups. In the globalized internet age we live in, it is easier than ever to reach out to people interested in the same topics we are but are oriented toward the world differently, so why doesn’t that happen? Why does the imagined audience of so much scholarship about China continue to be white and male? As a Black feminist, part of my motivation in beginning my project, Black Voices on Greater China, was to put a spotlight on Black women like myself and other Black individuals who have been left behind by current efforts to be inclusive toward those who have been traditionally excluded. I’ve been glad to see that since doing so, many new and similar organizations have garnered attention as well. There is certainly no reason more progress on this front cannot be made, as intersectional and interdisciplinary approaches and interventions involving Black feminist theory are frequently employed by our counterparts in Latinx, Native American, women’s, and Asian American studies.

Critical race and legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw originally coined the term intersectionality to describe structures of bias and violence against Black women. Since then, intersectionality has come to be used as a descriptor for the historical framework used by many feminist, LGBTQ, and antiracist scholars and activists to deepen an analysis of power and oppression across multiple axes. I believe China studies would be greatly enriched if Black feminism were an integral part of its curriculum and practice because it provides tools for thinking about the unrelenting patriarchal gaze imposed upon people in various cultures and how to subvert it without pushing for greater proximity to Whiteness or elite class status to do so. As opposed to what is sometimes aptly referred to as mainstream or “white feminism,” Black feminism recognizes that liberation cannot be achieved by applying the same tactics to all people. Instead, we must understand our respective positionalities and unite in solidarity against the structures that oppress us.

Kori Cooper is a J.D. candidate at Columbia Law School, an affiliate of the school’s Human Rights Institute, and a Davis Polk Leadership Fellow. She founded and leads “Black Voices on Greater China,” a project focused on amplifying Black voices and perspectives in the field of Chinese Studies. You can follow her on Twitter @Cooper_Esquire.