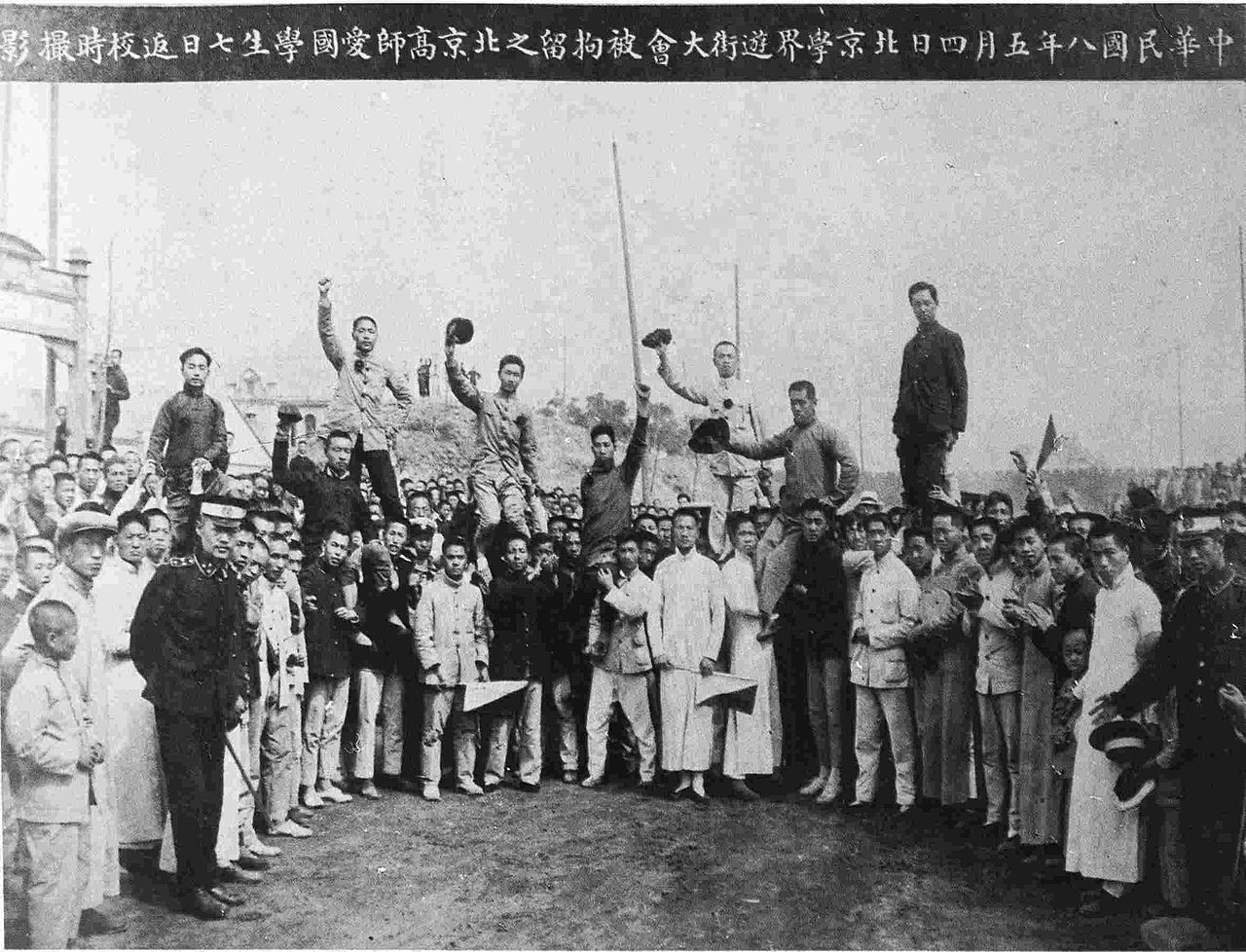

The 1919 May Fourth movement was pivotal for the formation of modern China. While it is most commonly known today as a popular movement against traditional values that called for modernization, May Fourth was also a radical student and worker-led movement that opposed both Japanese and Western imperialism. But even 101 years later, its historical legacy under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) remains contested.

What were once genuine anti-imperialist demands for self-determination are now used to justify a nationalist project of self-strengthening.

Founded on the heels of the May Fourth movement, the CCP continues to celebrate it as part of their official historical narrative. However, the CCP’s invocation of the movement has fixated on a nationalist framing: what were once genuine anti-imperialist demands for self-determination are now used to justify a nationalist project of self-strengthening.

For the CCP, portraying the May Fourth as only an anti-imperial movement is extremely tactical given its current geopolitical conflict against the United States. Chinese nationalists will use any opportunity they get to remind Chinese people all over the world that, just like the May Fourth movement over a hundred years ago, Western empires will humiliate and take advantage of China and its people. Of course, what is left unsaid is that the CCP has not only cracked down on the student and labor movement at home, but has transformed China into an exploitative empire in its own right.

Indeed, the CCP has to be selective in its depiction of the movement, otherwise casting themselves as victims of Western hegemony will no longer make sense. The movement’s ethos of undermining authority and the fact that it was led by students and workers are often left out of the nationalists’ narratives. Many nationalists do not even bother making the distinction between May Fourth reformers, who were more totalizing in their call for overturning past culture, and late Qing reformers, who called for the preservation of tradition alongside the adoption of some Western practices, primarily in the realms of science, technology, and government. Some contemporary invocations of May Fourth have even vouched for Confucianism, despite the movement itself being pointedly against it.

Furthermore, while May Fourth writers may be enshrined as literary icons in official hagiography, their actual writings have been removed from curriculums because they encourage the questioning of authority. In a memorable incident last year, a bot tweeting quotes from Lu Xun, a literary icon of the movement, was shut down by authorities in Shenzhen.

Given the CCP’s authoritarian regime, perhaps the most uncomfortable aspect about the May Fourth movement is its demand for democracy. A prominent slogan of the May Fourth movement was the call for “Mr. Science” and “Mr. Democracy,” as articulated by Chen Duxiu, who eventually went on to become a General Secretary of the early CCP. However, this call for democracy was conspicuously absent in celebrations of the centennial of the May Fourth movement last year, with focus placed instead on “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people.”

Despite these contradictions, the CCP has managed, by and large, to paint the May Fourth movement as part of their nationalist project. This is why it may seem unusual to cite the May Fourth movement in the context of Hong Kong or Taiwan. For both regions, the movement has become a tool of pro-unification nationalists and is seen as something that solidifies a unified Chinese identity.

The [May Fourth] movement has become a tool of pro-unification nationalists and is seen as something that solidifies a unified Chinese identity

However the radical legacy of the May Fourth movement, specifically its massive student and labor uprisings, must be remembered as a momentous event of the global Left’s history. Unlike previous uprisings, such as those that attempted to curtail the power of the Qing dynasty, the May Fourth movement was the one of the first times in modern Chinese history that those from the lowest rungs of society stood up to fight for their own empowerment.

What the anniversary of the May Fourth points to is, in many ways, that this movement, which started over one hundred years ago, remains incomplete. The movements in Hong Kong and Taiwan are a continuation of this struggle; though this time, this is not just a fight against Western imperialism, but Chinese imperialism too.