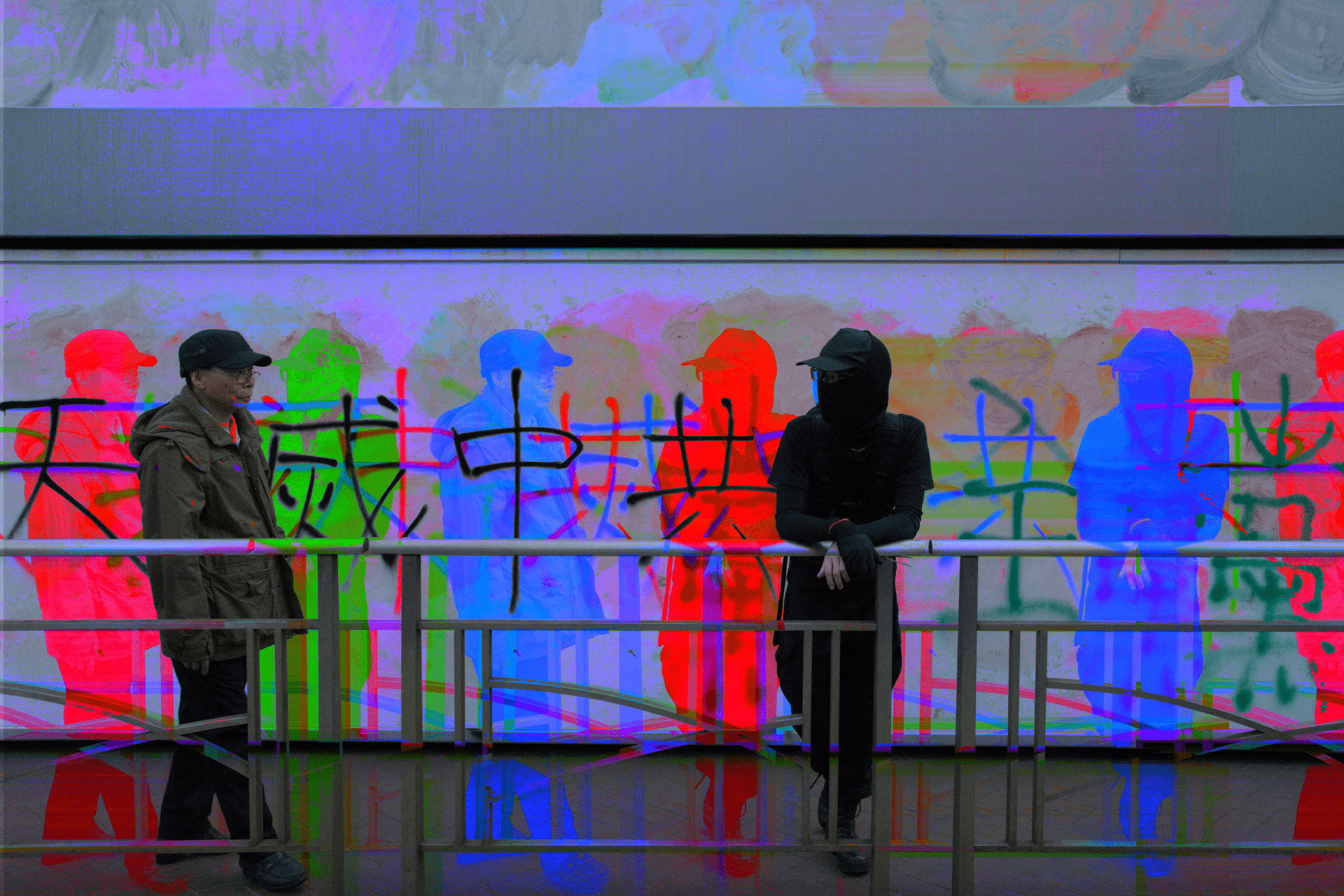

Original: 【香港民主运动映照下的大陆左翼】, published anonymously by 樱桃社, a Marxist-Leninist microblogging collective from mainland China

Translator: Irene

This article has been edited for clarity and precision.

Editor’s note: This translation of a short post by the mainland Chinese Marxist-Leninist “Cherry Commune” from 2020 is an exhortation to other mainland leftists to rethink its own practices in relation to the Hong Kong protests, which they admit shook the foundations of capitalist governance more than the mainland left has been able to. Their analysis forwards a Marxist-Leninist understanding of revolutionary vanguardism, which takes a critical stance against the “sub-cultural” political expression of leftism under authoritarian repression. Instead, they emphasize the primacy of proletarian base building, which they argue will inexorably allow leftists to “occupy secure political space even under ruthless CCP suppression.” This is, according to the authors, a prerequisite necessary for the mainland left to “catch up to and surpass Hong Kong’s democracy movement.”

While our own political analysis is at odds with much of this thinking (especially its vanguardism and the authors’ suggestion of the obvious and undeniable nature of such methods), we publish this because their emphasis on pushing theory into action is important—even if we believe the two cannot be so cleanly separated, conceptually or in practice. We also believe it is important to not only highlight the diversity and liveliness of political debate amongst the grassroots left on the mainland, but also to note the authors’ self-reflexive call to relate to the Hong Kong protests—and Hongkongers writ large—in ways that are not proscribed by the state or leftist orthodoxy.

Originating from popular opposition to extradition laws, Hong Kong’s democracy movement has now lasted for more than a year. It has not only mobilized millions of people and profoundly altered Hong Kong’s political and cultural ecosystems, but also intensified the inter-imperial power struggle between China and the United States, thereby becoming a major historical event in the 21st century. Geographically speaking, this popular political movement is only a stone’s throw from the mainland; despite severe and total opposition from authorities in Beijing and heterogenous (even antagonistic) ideologies, it has certainly galvanized and influenced left-wing opposition groups on the mainland.

The reasons for this are threefold. First of all, this movement and the mainland left share the same enemy: the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) bureaucratic, capitalist regime. “The enemy’s enemy is my friend” principle may not be universally applicable in practice, but witnessing damage done to a shared opponent inevitably inspires some degree of empathy and camaraderie. Secondly, popular movements of a grand scale tend to easily ignite certain romanticisms among revolutionary leftists, firing up motivation for mass self-education and self-liberation. With all this fervor for revolt, the mainland left has come to anticipate and reimagine the radical potential of Hong Kong’s democracy movement. Thirdly, this movement sharply and concretely highlights two essential though unresolved (or only partly resolved) issues critical to the mainland left: nationalism and democracy. The discursive foundation of the mainland left, on which many reflections and controversies have since sprung forth, was thus built on these three tenets.

Since the mainland left’s intellectual and cultural foundations are deeply influenced by Marxist-Leninism, its view toward Hong Kong’s democracy movement has more or less amounted to a formula: it is a bourgeois democratic movement entrenched in capitalist class conflict, largely dominated by the petit bourgeoisie, and in which some proletarians participate. As a result of such class antagonism, the movement’s limitations are significant, particularly in the lack of thoroughgoing demands, radical action, or close-knit organization. Given these shortcomings, the movement may destabilize the CCP bureaucracy’s proxy management of Hong Kong to some degree, but has little potential to achieve all the goals imagined by its participants. Instead, as the movement develops, internal divisions will arise out of class consciousness, thereby nurturing popular and political foundations for a more distinctly articulated class struggle in the future.

This movement sharply and concretely highlights two essential though unresolved issues critical to the mainland left: nationalism and democracy.

Reasonable or not, such a formula approaches the movement from a rather obstructed view. In other words, proponents of this mode of analysis tend to understand and critique Hong Kong’s democracy movement as a foreign entity external to themselves, instead of holding up the movement as a mirror for self-reflection or looking for ways to forge new connections. As such, their analysis remains purely theoretical and only useful insofar as they are predictive generalizations that attempt to define and assess. It is a rigid position that lacks self-reflexivity—unable to gauge nor measure the mainland left’s own transformative potential.

To move beyond such a narrow framework, the mainland left must first look inward and reexamine its own image as it gets refracted through the prism of the pro-democracy movement, taking seriously the many challenges and shortcomings that have bubbled up to the surface. It would then become clear that the mainland left has been occupying a diminished position, one whose political project remains uncertain. Unlike Hong Kong’s anti-establishment movement, it can scarcely muster up a political force powerful enough to agitate against authority, weaken its enemies, or even defend its own position. Currently, the mainland left’s impact is tangible mostly as a “subculture.”

Of course, any attainment of political status and creation of political force must start somewhere, whether in culture or material life. Social consciousness must find fertile ground for growth in both realms for class struggle to take root in the form of shared values, moral ideals, discourse, and theory. Only then can leaders be assembled, the movement’s ranks expand, and critique proliferate to fuel mass struggle. For these reasons, the emergence of any political force is inevitably first articulated in culture.

However, it is critical that a political force does not confine itself to a subcultural position for long. In fact, it would be in the interest of its growth to move beyond this phase as quickly as possible. This is because political demands in a subcultural phase often behave as simplistic thought exercises and emotional expressions, with only intellectual significance but no actual impacts. Faced with theoretical narratives created through thought exercises, individuals are left to learn, construct, amend, and assess through theoretical assumptions only. In reality, this means that political demands and narratives are stuck in a purely intellectual and idealistic existence, with no opportunity to be assessed in practice. This will inevitably corrupt the left’s politic and theoretical morale in the long term, and grand ideologies will be reduced to disguises for personal conflicts.

People will enthusiastically manufacture refined, anomalous, yet ultimately useless excuses in order to sustain a never-ending civil war limited within cultural fields. Therefore, practice becomes equated with theory, and theory becomes a paper tiger with no real usage. While steeped in the false satisfaction of explaining phenomena through theory, individuals simultaneously fantasize about participation in grand revolutionary practice. Ultimately, they’re only able to experience the joy of success and pain of failure through others, because their own activities never advanced to a stage where successes and failures are discernible. As such, when faced with real-life enemies, most leftists recoil at a few verbal threats far before the introduction of violent force, and shrink from action for self-preservation. This weak-willed state of cowardice and hypocrisy is profoundly and unequivocally damaging to the project of workers’ liberation.

To break away from the situation described above and achieve transformation into a political force, the left must focus on building a popular base. At its core, politics is an undertaking of the people, and political force is popular force. Certain demands only transform from culture into politics when they are accepted and pursued by the people. Only through the sheer vastness of popular support can political activities be continually sustained, supplied, and defended. As such, a political force can only be spoken of as such when a solid popular base is established. For the mainland left, this means going among workers and establishing personal, organizational, and intellectual connections with the proletariat, thereby transforming itself into a political movement with class-based roots. Only with this foundation can we further discuss the strength of political force, accuracy of theories, and the success and failures of political enterprise.

Many rebuke this with the argument that these strategies are culturally unadaptable. They believe that a certain amount of political breathing space is needed for supplanting the work of establishing and reinforcing a popular base. This space is guaranteed by Hong Kong’s relatively liberal domestic political system, but in an authoritarian mainland with no party-state separation, it obviously cannot exist. Therefore, many believe that leftists should operate according to the current situation, delay working among the general public, and stay concealed within a relatively safe subculture identity; following this, plans for proletarian work should only proceed once the CCP regime collapses and democratization movements succeed.

Political space is always a result of struggle and never granted from others.

This view appears logical, but is in fact absurd. This is because the foundation of its argument is rooted in an unrealistic fantasy about capitalist democracies: they imagine that under these systems, ruling capitalist political forces will obey abstract principles of democracy and provide all political forces, including leftists, with space to operate freely. This is a fantasy because although politics appear saturated with abstract theories, it is in fact thoroughly practical. As such, it is always practical forces rather than abstract principles that decide the distribution of political space.

For leftists, the kind of political force discussed here refers to a popular base itself, as well as the degrees to which this base is organized and politically conscious. For these reasons, the mainland left cannot hope for growth without building up a strong popular base among the working class: under a capitalist democracy, not only will the ruling class not grant political space to the left, but it will also seize the opportunity to legislate against communism, label leftists as anti-democracy activists, and forcefully apply bourgeois dictatorship. Instead, once popular and class-oriented bases are constructed, leftists will occupy secure political space even under ruthless CCP suppression. Political space is always a result of struggle and never granted from others; forgetting this equates to self-hypnosis. If the left loses sight of this, it will never take up space in the political theatre, let alone liberate the working class.

It is time for individuals to abandon unrealistic fantasies and turn towards concrete foundations, both through imagining ways of breaking down horizontal barriers between themselves and the working class, and through organizing and intellectual work to establish and reinforce a popular, class-oriented base. Only then can the mainland left rid itself of empty intellectualized stagnation, catch up to and surpass Hong Kong’s democracy movement, and become a political force capable of actual strikes against its enemy.