Editor’s note: Black Window, formerly So Boring, became known for their anti-capitalist, pay-what-you-want public dining space in Yau Ma Tei. In a city where every minute element of daily life is capitalized, carving out a space where eating, conversation, film screenings, and workshops can resist those strictures is a radical act of community building. So Boring’s refusal of the hyper-capitalist nature of commodifying life itself put Guy Debord’s exhortation “ne travaillez jamais” (never work) into practice.

The text below is Black Window’s summation of the city’s present crises, one that insists on holding space for the development of knowledges, skills, and practices that aim to undo the capitalization of Hong Kong life. This outlook, they make clear, is not antithetical to supporting the “yellow ribbon” camp but it approaches with different priorities: They see opportunities to build, create, and exist beyond the economism of the “yellow economic circle,” for example, as critical to widening our idea of what it means to survive in Hong Kong.

Black Window is currently holding a fundraiser until July 10 to help re-open their dining space and infoshop. The members have done several recent interviews in Chinese. An English interview with Lausan is forthcoming. For information on how to contribute to the fundraiser, and the full campaign text, visit their Indiegogo here. Updates on their activities can be found on Facebook and Instagram.

We are…

a group of friends, many of whom first encountered each other in the year-long occupation of the basement of HSBC bank headquarters in 2011, who have come together out of a combination of contingency and necessity. Whether we found one another in guerrilla gig moshpits on the streets, transporting subwoofers to contraband parties in abandoned bus depots or warehouse roofs, huddled close in ramshackle forts and treehouses defending farmland in the Northeast territories, sleeping on couches beneath flyovers staring at the stars with homeless friends facing eviction, encamped in tents on the water, singing karaoke with dockworkers on strike, or—as it turned out in the end—running a tiny makeshift al fresco vegan kitchen-cum-infoshop in a cul-de-sac cut off from the rest of the city, we are, down to the last of us, spawn of an unremittingly hostile environment, a metropolis that deems every form of living, every inch of inhabited territory that runs contrary to the mandates of the market to be a threat.

In Hong Kong…

The sensational events of 2019 appeared to have drawn international attention to the ongoing catastrophe that is our city, but the narrative that surrounded the warfare was often couched in terms that are in danger of obscuring the stakes that were in play. In order to solicit these sympathies and maintain them in the face of rapidly escalating events elsewhere, partisans in Hong Kong were compelled to style themselves as freedom fighters manning the crumbling ramparts of the free world, heralds sounding the siren of the approaching red deluge.

In the aftermath of the tumult, a solidarity economy (the so-called “yellow economic circle”) has formed among partisans to render services and assistance among one another, withdrawing resources, support and labour away from businesses that are on the side of the state and its footsoldiers.

This is, without question, an endeavor that is as worthwhile as it is necessary, but if we have, until this point, been hesitant to declare ourselves as being card-carrying members of the yellow economic circle, it is certainly not because we are situated on the opposite side of the ideological spectrum. Rather, it is because, for one thing, we do not define ourselves simply through economic terms as a food and beverage establishment (though of course we need to find the means to sustain the space and our own livelihoods), and for another, any “freedom that we aspire towards is not that of national sovereignty or political “independence,” but the power to—as the Situationists declared—produce ourselves and our own capacities, rather than the things that enslave us and separate us from our potentiality.

It is this very power, materialized in the collective skills, knowledges and practices that we are able to share and develop among one another, that we have always wanted to build, multiply and circulate. This is the only means by which we can begin to counter the despoliation, expropriation and impoverishment to which we have been condemned, by seizing and appropriating the wealth that surrounds us and putting it to a different use, that of building the bases for a different life, and the means to defend it.

A space needed…

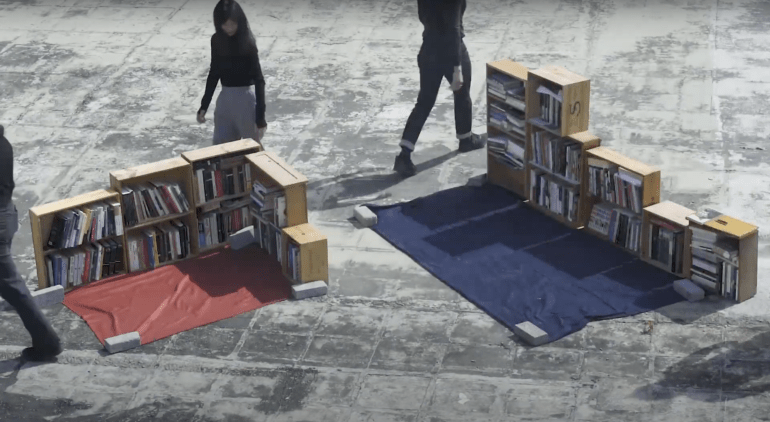

For this circulation and this sharing to take place, however, it is obvious that we require actual sites and places to meet and conspire, territories that we can claim and consolidate as our own, where we can speak, think and live among friends, where those in need can find shelter, refuge, care and substantive sustenance, physical and spiritual. We are in dire need of maps that indicate territories, provisional or permanent, that we have seized, that we are cultivating and that we must protect. A cartography that tells you where you need to go if you want to learn how to code or farm, if you want to pick up kendo, kickboxing or parkour, if you are interested in the rudiments of acupuncture or yogic breathing, if you are in search of contraband texts on occult subjects and a means to reproduce them for distribution among all of your friends. It is our hope that we can make a modest but enduring contribution to the building of such a place.

From So Boring to Black Window

In a previous incarnation, we were once known as the So Boring kitchen, a ramshackle hole in the wall vegan “restaurant” operating on the street. On any given night, you could show up and find yourself faced with a menu packed with dishes that you had never heard of, pairing, perhaps, a Cantonese soup with a West African stew and Thai pudding for dessert. For lack of waiting staff, you would have to find a place on the curb among a throng of misfits, place an order in a cramped, noisy hole-in-the-wall kitchen and patiently await the arrival of food that could very possibly be sold out by the time the cooks begin preparing your portion.

Despite all of this, So Boring became an infamous destination for the adventurous, the destitute, and of course those who wanted a nutritious meal and company without having much money to pay for it. So infamous, in fact, that the district councillor became as ardent to snuff out this den of vagrants as he did all the impromptu homeless shacks that have been wiped out in the area over the years. Tired of the constant raids by government departments invoked by the councillor and realizing that our tiny space had perhaps exhausted its potential, we decided to close the space and the street that we had inhabited with friends near and far for the better part of 6 years.

Too much of our time and energy, time that could have been devoted to endeavors that were far more worthwhile, was occupied in our efforts to evade and defy the letter of the law, dodging punishment for not being a properly licensed and registered restaurant. This evasion was not motivated by a simple taste for criminality, we simply did not regard ourselves as being a restaurant, and we certainly didn’t treat the street as the dining room for a food and beverage establishment.

The space that housed our kitchen just happened to serve food, but serving food was simply one among many things that we did, though it eventually became the case that everything else that we did was eclipsed by the kitchen, its notoriety and the demands that it placed upon those of us who had to keep it running through times of scarcity and need. Also, there was the fact that people who came to the kitchen had no real idea about the people behind it, what exactly their principles were beyond the odd political pronouncement every now and then on our social media, what other things they were engaged in. As a consequence, it was easy to mistake those of us in the kitchen as being “chefs” in the business of cooking for clientele.

It is clear, then, that we need a considerably bigger space, for one thing, and that we need to license and register it properly, for another, so that we don’t waste inordinate amounts of time devising strategies to outsmart the authorities. All of this attention and concern will instead go into coordinating screenings, curating our library, organizing discussions and workshops, as well as creating a solid and sustainable basis to support ourselves and, hopefully, other folks that require our support or assistance (for example, So Boring once ran collaborative nights with the Bethune House, which provides shelter for domestic migrant workers in need, and which was facing closure because of the withdrawal of funding).

Because we have resolved to maintain appearances and adopt the guise, superficially at least, of a “legit” restaurant, this will create costs and headaches that we have never known before. This is also why, despite all of our own efforts to save money ourselves, we are asking for your kind and deeply appreciated assistance to build the foundations of our space, and to help us establish a reserve fund so that we can weather the unpredictability of the post-pandemic climate and create a foundation upon which we can continue to build for the next few years.

Farewell Yau Ma Tei. Looking forward to seeing you all again.