Originally published in Upping the Anti. Republished with permission.

On November 11, 2017, with the help of security guards, the police broke into a classroom at Guangdong University of Technology and arrested eight students. As members of a leftist student book club, they were hosting a discussion on contemporary Left politics in China. In a published online post, one of the arrested, Zhang Yunfan writes:

In the reading group when we were arrested, we were discussing social problems and history in the last few decades such as the status of workers. We were asking: how can the youth think through and resolve these social problems? We did talk about what happened twenty-nine years ago [referring to 1989]. But were we ‘too radical’? Of course, if we define ‘radicalism’ by the book. In China, recognizing social problems is already radical; talking about how to address these issues is far more ‘radical’. But every country in this world has its social problems, different people approach them in various ways. Why is this illegal?1

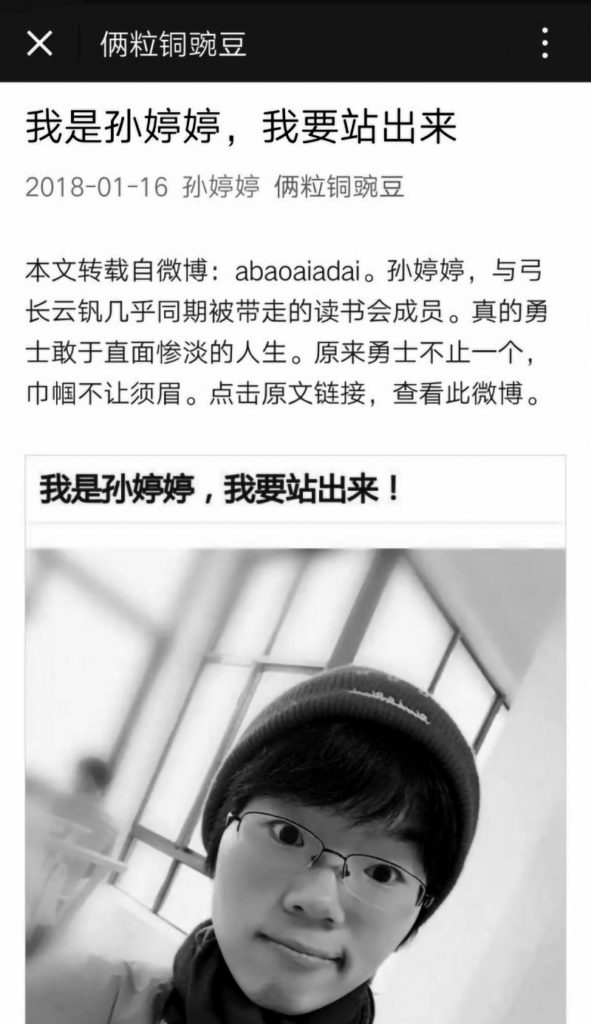

Yunfan, a leader of the book club, was charged with “disturbing public order” because they did not have their IDs when apprehended. Later, the police stormed the apartment of the book club co-organizer Zhen Yongming, arrested him, and confined him to the police station. Another victim was Sun Tingting who was detained on criminal charges. Four more student members who luckily escaped were wanted by the police.

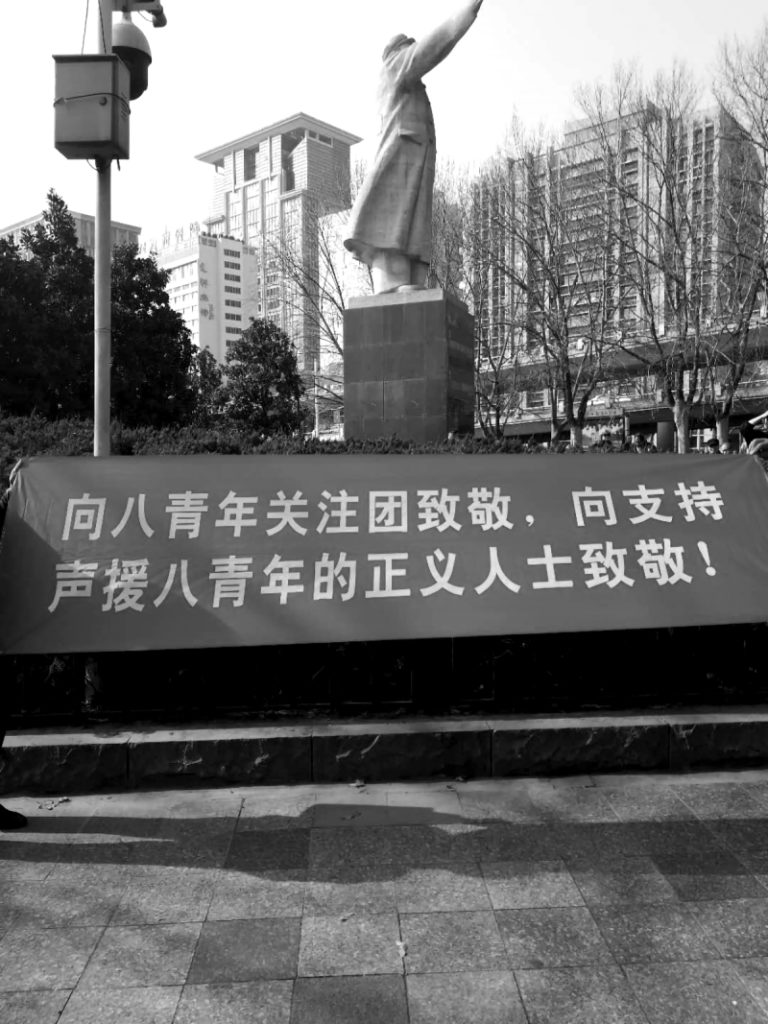

The absurdity of the arrest was met by opposition from other leftist groups. Indeed, the site of dominance is the site of resistance.2 Leftist organizers (myself included) across the country (see figures 1 and 2) as well as in Hong Kong (see figure 3) have joined forces online and offline to reveal the extremism of unlawful police violence and their paradoxical claims. More importantly, those who were arrested issued their statements on social media (see figure 4) once they were temporarily released on bail. The police did not expect this as they assumed students would remain silent because of the level of terror they employed. Eventually, all the students were released in early 2018.

Students are not the only people being policed. For example, several leftist lawyers offering free legal counsel for migrant workers in the Pearl River Delta were arrested in late 2016.3 These arrests and detentions point to a struggle around the definition of socialism in the context of post-socialist China. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) claims to be socialist in nature. Due to the limited scope of this article, I cannot unpack fully the CCP’s insistence on “socialism.” Yet, as the Chinese historian Wu Yiching points out in a recent paper, this claim of socialism is devoid of any socially-just meaning as state capitalist formation unfolds.4 To respond to how “socialism” has been enacted by the CCP, this piece proposes theories and praxis that offer historically grounded conceptions of Chinese socialism.

When discussing China within the context of the post-Cold War and post-socialist era, it is best to be cautious about two reductive tendencies. First, there is the bifurcation between pro/anti-state positions. Without fully understanding the complex Chinese modern nation-state project, Anglophone media, including radical publications such as Dissent Magazine, considers any anti-statist positions to be “radical.” For example, pro-free market dissidents like Liu Xiaobo have been branded as the “right” kind of dissident;5 while the actually existing Chinese New Left is branded as “working with the Chinese State.”6 Second, Cold War orientalism is present in how China is described by both liberal and conservative media.7 Cold War orientalism is understood as the continuation of Cold War “othering” of communist countries as “perverse, totalitarian, barbaric, and undemocratic” and, thus, these countries fail to reach a “normal, democratic, and civil” modernity. Scholars of Chinese studies often criticize the Chinese government from such a standpoint, portraying Chinese capitalism as the “improper one,” which serves as a kind of political branding for neoliberalism as “the good capitalism.”8

This article is written against the grain of these prevailing assumptions and binaries. In the following pages, I will first give a brief but historically grounded understanding of the so-called transition to capitalism. The point I make in the first section is that the statist capitalist reform might be fathomed as a passive revolution to ease the potential mass organizing in the afterlife of the Cultural Revolution. Second, although the integration of global capitalism helps to stabilize the hegemonic political elite who have deployed socialism as a discourse for the past 20 years or so, theories and organizing, largely underground, have been developing and providing the possibility for critical socialism, a type of socialism that sometimes converges and diverges with the state socialist discourse mobilized by the CCP, which some Left activists call Huang ma 皇馬 (Imperialist Marxism). What I wish to focus on is not if China or the CCP is still socialist; rather, I am interested in bringing socialism from the hegemonic and centralized state back to the everyday struggle in workspaces, sweatshops, and communities.

Some notes on Chinese socialism, the state, and class

In many Marxist writings, the current neoliberal moment is narrated as a radical discontinuity from the socialist past. Works by William Hinton, Martin Hart-Landsberg, and David Harvey all lament the expansive class division after marketization.9 Yet, these theorizations assume that 1) equality existed during state socialism; and 2) capitalist shifts happened because Mao Zedong passed away and Deng Xiaoping, “the capitalist roader,” acquired power. These assumptions not only have little historical evidence but also do not offer a systematically developed analysis of how the capitalist reform took place, the historical forces behind it, and under what historical conditions the CCP leaders decided to reform.

In this section, I offer an understanding that does not romanticize the Maoist socialist era (1949 to 1976) nor deny its legacies. This interpretation focuses on the shifting power and reorganization of the hegemonic power within the CCP, and the counter-hegemonic power from diversified fronts. First, inequality continued throughout the Maoist socialist era and the capitalist reform is the reorganization of these disparities. To elaborate, during the early and mid-1950s, the mass agricultural collectivization and industrial urbanization did not fully dismantle class. In fact, the direct state control of resources without the supervising apparatus brought about new configurations of inequality: 1) the higher-level bureaucratic class had more access to political and material resources than an average worker; and 2) the abolishing of private property took place in theory, but in reality it created a condition in which a group of political elites owned the means of production by controlling the Chinese state apparatus. As Wu Yiching asserts, Chinese peasants and workers in the socialist era were as proletarian as migrant workers today.10

The state-led marketization and privatization since the late 1970s have augmented these continuing inequalities. More specifically, the privatization of state-owned enterprises has amplified the inequality of access to state resources that existed before the reform and open-up. Processes of privatization engendered the alliance between the political elite and capital, which might be termed “the red bourgeoisie.” In this new bloc, the political and bureaucratic elite have enormously benefited from their monopoly on political resources to garner public assets and more recently to protect capitalist interests that they have also been investing in largely due to their political privileges.11 A well-cultivated capitalist class forged through governmental favours and kinship (some of the capitalists are in fact relatives of members of the political elite) has been powerful in the last decade. For example, the Taishan Hui 泰山会 (Taishan Club), comprised of the CEOs of Wantomg Pharmacy Co., Lenovo, Alibaba (internet retailing), Huayi Brothers Media Group, Fosun Group, Fanhai Group, and others, is one of the most secret capitalist circles in China.12 Therefore, it is fruitful to consider state capitalism in China as a party-state-led social engineering process where “a low transparency and low welfare”13 national context necessitates the Party-State’s role as an active market agent and engineer.14

Second, the market reform can be perceived as a passive revolution on the part of the political elite within the CCP to quell political unrest in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. Politicized discontent with the bureaucratic class’ access to state power and resources was sustained after the Cultural Revolution. This popular dissatisfaction coincided with stagnated production and increasing work sabotages.15 After the Cultural Revolution and the 1976 Tiananmen Gathering, the Democracy Wall movement emerged in 1978. Many underground publications contributed to the increasing number of wall posters in major Chinese cities, criticizing the inequality within the socialist state.16 A social movement that inherited the legacy of mass organizing during the Cultural Revolution was again on the horizon. On the brink of such deep changes, the political elite decided to push forward the market transition as a pragmatic solution to people’s frustrations.

These insurgencies became obvious threats to the political elite in the late 1970s; and amid these intensified organizations, the leaders gathered at the Party headquarter and announced the shift of the aim of the Party to “socialist modernization.” This was the official start of market reform. In this sense, 1978-1980 was central to the orientation of the Party and indeed to the path China would take. It is under these circumstances that the post-Mao capitalist path ought to be conceptualized as a response to the self-organizing of the people unleashed by the Cultural Revolution, especially amongst the more radical factions.17

We can think of the capitalist shift as Gramsci’s passive revolution, a strategy the CCP initiated to ease the disillusioned grassroots and to stabilize its hegemonic position. These reforms were conducted with calculated approaches to keep the political elite intact. Designed for the transition to material modernity, marketization inevitably shapes the subjectivities of the government officials, ordinary Chinese people, and the CCP. One consequence of these openings to capital is invigorated class inequality that further dissatisfies workers throughout the country. Another product is a rising counter-hegemonic self-organizing that differentiates socialism with revolutionary and social justice potentials from socialism as state rhetoric that might lack intent for social justice and equality (the CCP ideology). The former socialism can be termed as critical socialism because it brings socialism back into the factories and migrant villages, providing counter-hegemonic potentials.

Critical socialism in post-socialist China

Critical socialism emerges out of current discussions within the New Left, liberalism, and New Confucianism in contemporary post-socialist China.18 The New Left in China emerged in the post-Cold War context. One leading figure of the New Left, Wang Hui, has repeatedly questioned the pursuit of capitalist modernity; others like Gao Yang and Cui Zhiyuan have carved out a “liberal-left” discourse since the 1990s.19 Overall, New Left scholars acknowledge that contemporary inequality in China is the direct result of capitalism; yet they differ from each other on the approach to solve inequality. Some wish for a comeback of Maoism, while others aim to conceptualize ways out of China’s past socialist practices within the confines of the Party-State. Liberalism advocates for a market free from governmental regulation and understands widening inequality to be a result of the “gangster logic” produced by the excessive presence of the state.20 New Confucianism is an increasingly important rising public discourse that can be traced back to the 1980s. The “China” model that retains traditionalism to explain the expensiveness and competitiveness of the Chinese economy was a well-known articulation by various state-leaders such as Lee Kuan Yew. Outside of China, the neo-Confucian mentality sees reformist China as finally “back on track of the capitalist road.”21 After 1989, for instance, Deng Xiaoping sent delegates to Singapore to learn how to prevent social unrest from happening, and a renewed Confucianism came to the rescue.22

The resurgence of socialism, what I call critical socialism, can be understood as community-based socialisms derived from grassroots organizing, even though some organizers might not explicitly identify as socialist or Marxist.

These intellectual camps have shaped many aspects of socialist party politics in China, yet the grassroots part of the story is missing. In fact, what intellectual contributions often neglect is the everyday struggle of ordinary workers who demonstrate a desire for justice and socialist commitment. This nuanced interest in socialism differs from the liberal personhood mandated by post-1989 economic neoliberalization and does not fit into the state socialist rhetoric. The resurgence of socialism, what I call critical socialism, can be understood as community-based socialisms derived from grassroots organizing, even though some organizers might not explicitly identify as socialist or Marxist. How is critical socialism different from socialism as rhetorically deployed by the Chinese state? In this section, I outline some key points of critical socialism. The most critical potential, as I demonstrate using two cases, lies in what can be called community-based and localized forms of socialism. It is my intention to challenge what we know as socialism proper and to argue for attention toward critical and community-based socialism in the destructive afterlife of racial capital in post-socialist China.

To speak of socialism in China is to conjure up particular memories of the Maoist era. For the generation that grew up in the reform era (post-1980s), Maoist socialism represents a time of brutality and disruption to Chinese modernity. The association of socialism with trauma and chaos tends to prompt the post-reform generation to opt for a future promised by consumerism.23 The bloc of political elite-capital builds its justification to power and developmentalism around this desire to forget the socialist past.

Critical socialism can be understood as an attempt to delink socialism from the Chinese Party-State. That is, we are witnessing a counter-hegemonic definition of socialism grounded in labour organizing and worker power, as opposed to socialism as state rhetoric. One such example is the Jasic incident. In 2018, leftist students in China travelled to Pingshan to support striking workers in factories owned by a company called Jasic.24 Workers and students demanded independent unions, better pay, and no military-style labour control. After 10 days of intense protests, local police finally arrested strikers and demonstrators.25

The Jasic incident received international attention and was labelled as the “new age” of Chinese labour organizing by Western media. However, as one can imagine, it is not an outlier but the result of continuing labour struggles. In the early 2000s, a group of Maoists came to the Pearl Delta Region, hoping to organize the growing number of migrant workers. Their efforts have grown over time, with new recruits including newly graduated university students and workers. One strategy they adopt is to secretively plant underground labour activists as factory workers. This plan has yielded some successes over the years, yet labour activism remains fragmented and successes are case-by-case. Nevertheless, because of these existing relations, Maoist students and workers were quick to organize the Jasic Workers Solidarity Group days after the initial strike started.

There is, nonetheless, a conflict between the workers and the Jasic Workers Solidarity Group around socialism. This discrepancy is not to be taken lightly. Rather, it points to the core of this essay: what is socialist organizing? In other words, can the workers’ strike effort be a form of socialist organizing? It is easy to offer a negative answer as the workers are not well-versed in socialism or Maoism. But as an organizer myself, I know that a community-based and worker-centred approach is key to successful organizing, whether explicitly socialist or not. For instance, the workers’ frustration stems from their inability to dictate the terms of their working conditions and to form independent unionization, which would be a first step toward socially just changes in China.26

Yet the students in the solidarity group are committed to socialism, a theory that might not be shared with the workers. For example, throughout the interactions before the strike, the hegemonic discourse of socialism was never present in workers’ discussions.27 It was only after the Maoist group showed up that slogans of Maoism and socialism were mobilized.28 It is crucial to see this tension between the student-worker solidarity that emerged in Jasic, and the community-based, socialist possibilities workers themselves point to.

In addition to the return to worker power, critical socialism diverges from socialism as state rhetoric by merging with other grassroots social movements in post-socialist China. Unlike the Western-centric narrative that sorts labour, feminist, queer, and trans liberation in a sequential and linear timeline, workers organizing in post-socialist China have already been part of the liberation for sexual minorities and the women’s movement. In other words, as opposed to the CCP-sanctioned socialism that sometimes falls short on issues of queer, trans, and women’s liberation, critical, community-based socialism has been attentive to feminist and sexual liberation. One such effort is a group that I am involved with: Ku’er Gongyou 酷兒工友 (Queer Workers).

Queer Workers is an organization that provides services for queer migrant workers in the Yangzi Delta region.29 Established in Suzhou in 2016, it aims to promote queer liberation from a leftist stance. Situated in a region populated with migrant workers, it has provided valuable resources for many who are excluded from shopfloor circles, village friends, and local queer communities. Apart from organizing grassroots conferences like The Left Looks at Contemporary Tongzhi Movement, the group has also published their first book Shehui Zhuyi yu Tongzhi Jiefang (Socialism and Queer Liberation), which is available in Hong Kong and Taiwan, but ironically, not in mainland China.

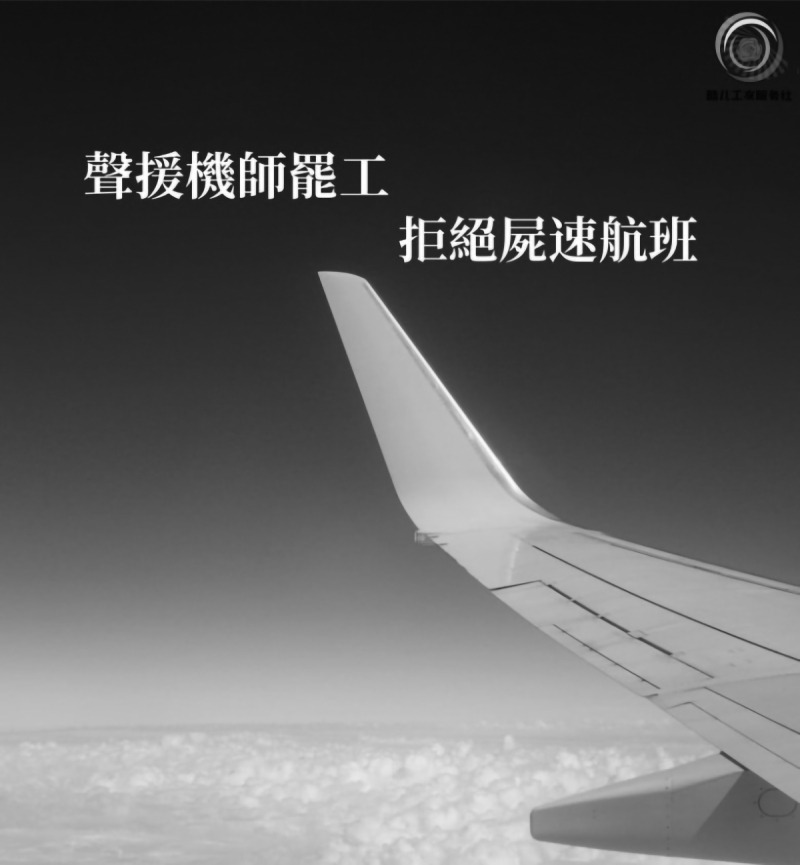

What distinguishes Queer Workers from other queer groups is perhaps its dedication to labour and workers’ rights, on which they take an internationalist perspective. In 2019, pilots working for China Airlines in Taiwan went on strike. In a country where striking is not a common tactic, the struggle attracted much attention. Queer Workers, although based in China, was the only Chinese LGBTQ organization that expressed solidarity with the airline workers and published a statement signed by other activists. Some of their posters were distributed to online chat groups of migrant workers who identified as sexual minorities (figure 5). For those who understand geopolitics in Cold War China, the move by Queer Workers is significant. First, capital flows across borders, thus workers’ rights should also trouble Chinese nationalism. If, as the saying goes, “A worker has no country,” then centring international workers’ rights challenges nationalist border-making. Geopolitical debates about Taiwan and China are tense conversations. Yet these discussions sometimes fail to see how migrant workers in China working for outsourced Taiwanese factories are connected to workers in Taiwan. Queer Workers’ efforts to highlight the centrality of labour struggles across borders indeed offer a different approach to think about the geopolitical tensions of the two Chinas. Second, it is a brave move for Queer Workers to engage with Taiwan despite the state-mediated nationalist discourse. For Queer Workers, solidarity is crucial because queer and socialist liberation will not be achieved unless workers in the region realize their common ground amidst various priorities.

At the intersection of women’s liberation and labour, Jianjiao Buluo 尖椒部落 (Pepper Blog) emerges as another important organization. Based in the Pearl River Delta, Pepper Blog publishes posts and organizes offline events for women migrant workers in the region. As a worker-led organization, it offers a clear alternative to liberal feminist advocacy in post-socialist China. For example, in 2019, the group organized film screening events in the factory zones of Shengzhen (figure 6). Unsurprisingly, the film being screened was American Factory instead of a film such as Bombshell. For women workers, everyday life in the factory tells the violence of capital. A popular saying circulating amongst some workers, both men and women, after the movie was that “資本不姓中或美,資本姓資 (the last name of capitalism is not ‘American’ or ‘Chinese’ but ‘capital’).” The film screening is a productive way of organizing because workers can see themselves as part of a larger system of production that links them to workers in other parts of the world. Other films include Lesbian Factory, a Taiwanese film about lesbian migrant workers demanding wages.

Additionally, Pepper Blog posts poetry written by women migrant workers. These collections highlight the violence of but also the desire for freedom from global racial capital. This desire-based and feminist approach to labour issues is undoubtedly unique in post-socialist China. Much of contemporary Chinese feminist advocacy centres around vocalizing oppressions and revealing trauma. Contrary to these methods, women workers, through Pepper Blog, write about their journies to factories and their dreams. Yet, by narrating dreams, readers see the everyday struggles for better lives and futures. For example, one of the poems, written by a child of migrant parents, who is also a migrant worker, reads:

无题

二十五年了

不明自己的来意?

像一片流云

风能吹散

雨能蒸发

软弱 无能 没出息

收好自己的标签

放在心底

论断淹没肉体

眼光穿刺灵魂

活下去

如果可以自由搏击

谁愿意用笔杆子书写愤怒?

如果有旷野厮杀

谁愿意做一头沉默的狮子?

Untitled

For twenty-five years

I don’t know why I am here

like drifting cloud made of pieces

evaporated into the air

blew apart by wind

incompetent, unsuccessful, timid

in my heart I hide

these labels

as criticism inundate my body

judgements penetrate my soul

live on, I say

but if I can fight freely

Why would I write my rage with pens?

If there is a field to run wildly

Why would I be a lion in silence?

Written by a young migrant worker named Ji Tong, this poem depicts the impasse between the desire to break away from constraints and the encompassing circumstances that one finds themself in.30 Starting with the disoriented feeling of rootlessness, the poet moves through the everyday experiences of being judged as she goes on with her life. These situations make her wonder about her worth, goals, and values. But despite obstacles, she holds on tight with her spirit. Indeed, she is a fighter, a lion in need of liberation. Even though she can only write and stay quiet, in silence, she rages.

This powerful poem underscores the impossibility of freedom within capitalist relations but also the desire for liberation that holds the space, time, and intention for women workers’ organizing and liberatory potentials. Although approaches like writing poems or film screenings can be read as ‘de-politicized’ in the North American protest scene, they are crucial parts of women’s organizing in post-socialist China.

Groups such as Queer Workers and Pepper Blog have been working to find new grounds for critical socialism. Their socialist sensibilities diverge from the Party-State’s discourse of state socialism. Their commitment to sexual and women’s liberation in the post-socialist present urges them to think about these topics through the lens of labour struggles and worker organizing. These are important lessons for critical socialism with revolutionary desires. Once again, workers and students are forging relations and reclaiming socialism from the Chinese Party-State, but this time with particular attention to sexual minorities and women’s struggles.

Conclusion

Binaries of “good state capitalism/bad market capitalism” and “undemocratic East/democratic West” have hindered contemporary radical political imaginaries. Resistance from the global Left has not responded to the complexities in China with historically and contextually grounded knowledge. What I call critical socialism in China calls for scholars to diversify the definition of socialism and to provincialize state-organized socialism as the only legitimate way to achieve anti-capitalist liberation. Groups like Queer Workers and incidents like that at Guangdong University of Technology suggest that the global Left has to build politics not exclusively on the grounds of anti-authoritarianism but on critical and community-based organizing across the landscape of “villages within cities (城中村)” in post-socialist China. Scholars and activists have to see themselves as constituent parts of a liberal project that brands China as “improper capitalism” to the extent that the role of the Chinese elite is missed within the transnational circulation of racial capital, commodities, and people.

Similarly, the political-economic elite’s role in global racial capitalism is of equal significance to a critical socialist critique. Insofar as global capitalism has been flexibly constituted,31 the abolishing of global capitalism and any local radical project are mutually constitutive. China’s rise within global racial capitalism is closely connected with multiple forms of extractive regimes. For instance, in 2017, mining was the largest sector of Chinese investment in Australia, yet many of these practices operate on Aboriginal land.32 In Canada, one instance is the failed purchase of Aecon by Chinese state-enterprise CCCC International Ltd. Aecon has been involved in construction on the territories of the Mikisew Cree First Nation as well as in the TransCanada pipeline. The Chinese buyout is arguably related to the system of settler colonialism.33 Such movement of transnational capital suggests that global solidarity is hard but necessary. By outlining critical socialism, I centre people’s experiences and knowledge-production that often gets elided in area studies and popular discourses of China. The emergent forms of organizing I describe provincialize what we know as socialism. And perhaps, as a placeholder for plural futures, critical socialism offers sets of possibilities from the Chinese experiences of nation-building and post-socialist transition.

Figures

Figure 1. an online callout poster.

Figure 2. a banner paying tribute to these youth.

Figure 3. protestors in Hong Kong

Figure 4. a screenshot of Sun Tingting’s post before being censored.

Figure 5. a poster for airline worker solidarity, Queer Workers’ logo can be seen in the top right corner.

Figure 6. workers watching documentaries in an industrial zone in Shenzhen, courtesy of Pepper Blog.

Footnotes

- The translation is mine. So are all the possible misconceptions and untranslatability. For the original text in Chinese, see Yunfan Zhang, ‘‘Wogui Renmin de Zibanshu (My Confession to the People),’’ 2018, from http://www.sdxf1917.tk/archives/20.

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, Volume 1, trans. R. Hurley, (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), 101.

- See Sui-Lee Wee, ‘‘China Arrests Four Labour Activists amid Crackdown,’’ Reuters, Jan 1, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-rights-idUSKCN0UO05M20160110; Chunhan Wong and Te-Pin Chen, ‘‘China: Court Sentences Labour Activist Lu Yuyu to 4 Years in Prison After Documentation of Labour Unrest,’’ Mar 27, 2019, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/china-at-least-19-labour-activists-detained-by-authorities-china-labor-watch-releases-statement-on-those-who-assisted-lide-shoe-factory-workers.

- Yiching Wu, ‘‘The Strange Case of China: History, Class and Chinese Post-socialism,’’ Boundary 2 46, no.2 (2019): 153.

- Barry Sautman and Hairong Yan, ‘‘The ‘Right Dissident’: Liu Xiaobo and the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize,’’ Positions 19 no.2 (2011): 581–613. https://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-1331832. Although I disagree strongly with Liu’s politics, I do not think he should be jailed and kept in prison. My position is always in support of the abolition of the police and prisons, especially since I was also threatened and arrested by the Chinese police for my queer organizing work.

- The “New Left” (Xin Zuo Pai 新左派) is distinguished from the old, orthodox Maoist Left. Leading figures such as Wang Hui, Gao Yang, and Cui Zhiyuan perceive capitalism as the main factor contributing to an increasing rate of inequality in China and have been interested in collectivism in the socialist era. I have to note that these conversations happen outside of the Party ideology, but traces of writings seem to support state control of the economy. For a detailed introduction of the New Left, see François Lachapelle, Anshu Shi, and Matthew Galway, “The Recasting of Chinese Socialism: The Chinese New Left Since 2000,” China Information 32, no. 1 (2018): 139-159. However, the New Left remains a collective of predominantly male intellectuals and sidelines women’s issues in most of their discussions. For a discussion on the New Left’s neglect of women’s concerns, see Sharon R. Wesoky, ‘‘Bringing the Jia back to Guojia,’’ Signs 40, no.3 (2015): 647-666.

- Christina Klein, Cold War Orientalism, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

- For some liberal critiques of the Chinese state, see André Laliberté and Marc Lanteigne, ‘‘The Issue of Challenges to the Legitimacy of CCP Rule,’’ in The Chinese Party-State in the 21st Century, eds. André Laliberté and Marc Lanteigne, (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2008) 1-21; Peter Lorentzen, ‘‘Designing Contentious Politics in Post-1989 China,’’ Modern China 43, no.5 (2017): 459–93; Xiaoguang Kang and Heng Han, ‘‘Graduated Controls,’’ Modern China 34, no.1 (2008): 26-55. DOI:10.1177/0097700407308138. For a critique of these liberal writings on China, see Patricia T. Clough and Craig Willse, ‘‘Human Security/National Security,’’ in Beyond Biopolitics, eds. Patricia T. Clough and Craig Willse, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 57.

- See Martin Hart-Landsberg and Paul Burkett, China and Socialism: Market Reforms and Class Struggle, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2005); William Hinton, The Great Reversal: The Privatization of China, 1978–1989, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1990).

- Yichi Wu, ‘‘Rethinking Capitalist Restoration in China,’’ Monthly Review 57 (2005): 44-63.

- Wu, ‘‘Rethinking Capitalist Restoration in China’’; Wang Hui ‘‘The Historical Origin of Chinese Neoliberalism: Another Discussion on the Ideological Situation in Contemporary Mainland China and the Issue of Modernity,’’ The Chinese Economy 36, no. 4 (2003): 10-13. DOI: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10971475.2003.11033470?journalCode=mces20. In Wang’s article, he details how bureaucratic managers of state-owned enterprises sold resources during the period of rapid privatization.

- Xie Lao, ‘‘A State Adequate to the Task: Conversations with Lao Xie,’’ Chuang 闯, February 2019, http://chuangcn.org/journal/two/an-adequate-state/. For an English source on the “Taishan Club” (the Taishan Industrial Research Institute, founded in 1994), see Li Cheng, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership, (New York: Brookings Institution Press, 2016), 174-5.

- Hui Qin, “Zhongguo Qijide Zaojiu yu Weilai: Huiguo Gaigeikanfan Sanshinian (The Formation and Future of the China Miracle: A Personal View of China’s Thirty Years’ Reform),” Southern Weekend, February 24, 2008, http://www.aisixiang.com/data/17672.html

- Fulong Wu, ‘‘How Neoliberal Is China’s Reform?’’ Eurasian Geography and Economics 51, no. 5 (2010): 625. DOI: 10.2747/1539-7216.51.5.619

- Jo-his Chen, Democracy Wall and the Unofficial Journals: An Annotated Bibliography Studies in Chinese Terminology. (Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, University of California, 1982).

- Yichi Wu, The Cultural Revolution at the Margins: Chinese Socialism in Crisis, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014); Shaoguang Wang, ‘‘New Trends of Thought During the Cultural Revolution,’’ Journal of Contemporary China 8, no.21 (1999): 197-217.

- Timothy Cheek, David Ownby, and Joshua Fogel, ‘‘Mapping the Intellectual Public Sphere in China Today,’’ China Information 32, no.1 (2018): 108. DOI: org/10.1177/0920203X18759789

- Timothy Cheek, David Ownby, and Joshua Fogel, ‘‘Mapping the Intellectual Public Sphere in China Today,’’ China Information 32, no.1 (2018): 108. DOI: org/10.1177/0920203X18759789

- Anshu Shi, François Lachapelle, and Matthew Galway, ‘‘The Recasting of Chinese Socialism,’’ China Information 32, no.1 (2018): 147. doi.org/10.1177/0920203X18760416

- For some liberal publications that espouse the market, see: Xueqing Zhu, Daodei lixiangguo de Fumie (The End of a Moralist Utopia), (Shanghai: Shanghai joint publishing, 2003); Jinglian Wu, ‘‘Zhongguo Gaige Jingru Shengshuiqu: Tiaozhang Quangui Zibenzhuyi (China’s Reforms Have Entered Deepwater: The Struggle Against Crony Capitalism),’’ Luye (Green Leaf) ½ (2010): 90-5; Weiying Zhang, “The New Enlightenment of Reform: The Chinese Transformation Propelled by the Market of Thoughts,” (Beijing: CITIC press group, 2014).

- Ya-Chung Chuang, ‘‘Democracy Under Siege,’’ Boundary 2 45, no.3 (2018): 70.

- Arif Dirlik, ‘‘Forget Tiananmen, You Don’t Want to Hurt the Chinese People’s Feelings, and Miss Out on the Business of the New ‘New China’!’’ International Journal of China Studies 5, no.2 (2014): 304.

- Lisa Rofel, Desiring China, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 125-6.

- Note that the CCP does have a national union, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). Independent unions are illegal.

- See the website for the Jasic Workers Solidarity Group: https://jiashigrsyt1.github.io/727oneyear/

- It remains to be seen how independent unions can work within a state that seeks to confine workers within the existing ACFTU. It is also worth noting that many workers in China are not unionized, such as those in temporary jobs, factories, and domestic work. Due to the limitation of space for this article, these discussions are unfortunately not elaborated.

- Personal Communication with Shen.

- The older cohort, mostly those who lived through the Maoist socialist era, tend to invoke Mao’s writing and thinking when they voice the support of workers’ struggles in the post-socialist present.

- See their website: https://site.douban.com/29 3169/

- For the poem in Chinese, see: http://jianjiaobuluo.com/content/107590

- John Holloway, ‘‘Global Capital and the Nation-State,’’ Capital and Class 18, no. 1 (1994): 23-49.

- KPMG and University of Sydney, Demystifying Chinese Investment in Australia, June 2018, https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2018/demystifying-chinese-investment-in-australia-june-2018.pdf: The KPMG & University of Sydney, 2018.

- The attempted buyout was blocked by the Canadian federal government, but the fact that Chinese capital tried to fund a company implicated in the settler-colonial project is indeed troubling.