Original:【為何申請五一遊行】and【關於今早經歷及被迫作出的決定】, published on Facebook

Translators: PL, WF

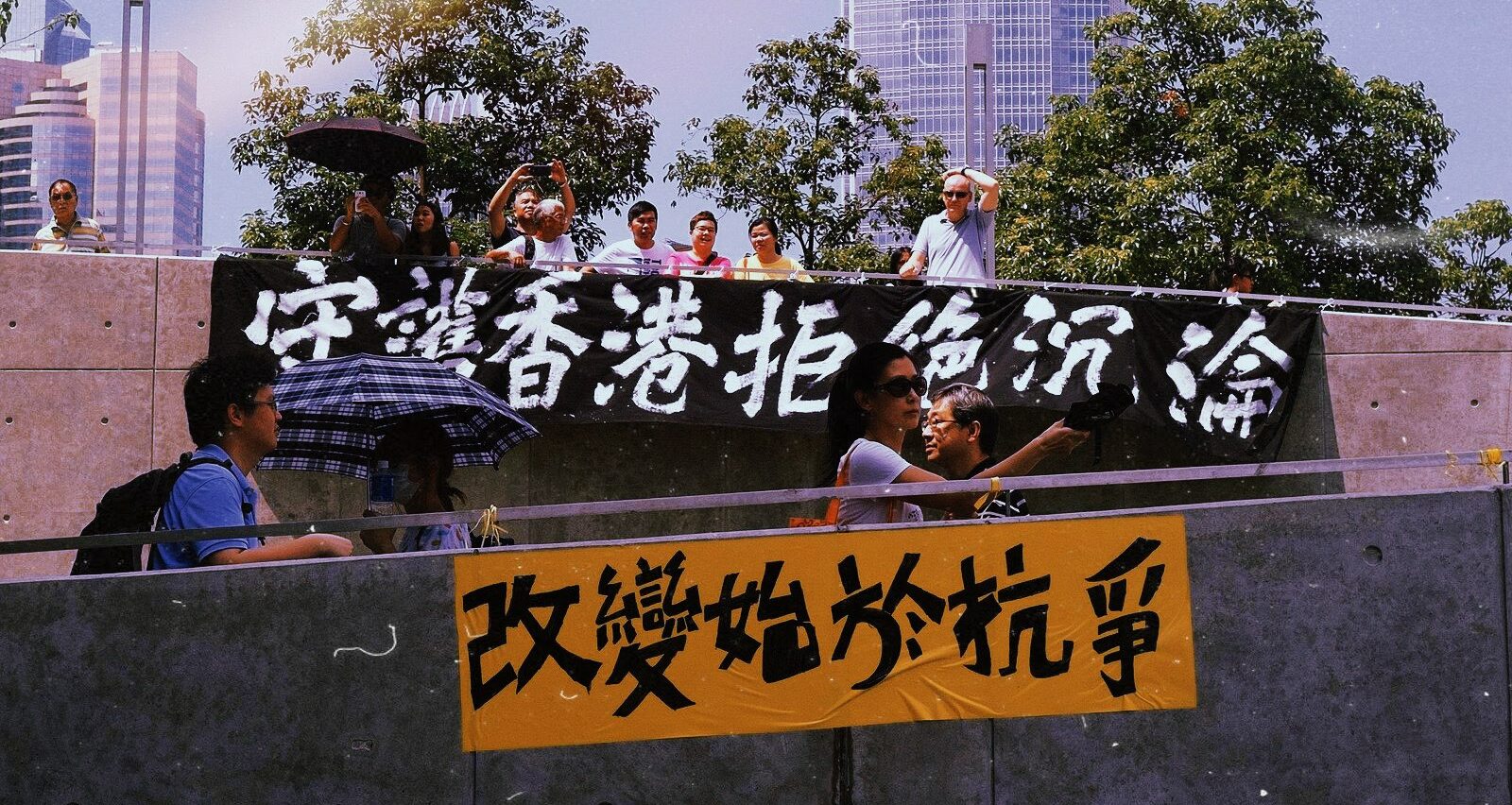

Translators’ note: The activity of social movements has sunk to an unprecedented low in Hong Kong’s recent history with the imposition of the National Security Law following the anti-extradition movement of 2019. Most public expressions of dissent have been criminalized or coercively discouraged by the authorities, with the exception of a small number of wildcat strikes. With the end of COVID restrictions on public assembly this year, activists hope to gauge the limits of public rallies under this new political climate. The picture of protest in this new climate thus far has been murky. Organizers of an International Women’s Day rally in March, the long-time labor group Women Workers’ Association, were pressured to cancel the day before the planned rally. A gathering by migrant domestic workers’ groups proceeded successfully on the same day, though the police still surveilled and took down the identification information of its participants. Later that month, a local protest against land reclamation in Tseung Kwan O was briefly thrust into the public spotlight for being the first police-approved rally since the National Security Law. The criteria set by the Hong Kong police was very strict: there could be no more than 100 participants; each participant had to wear a numbered identification badge around their neck while holding on to a cordon line in a strictly monitored formation; masking was prohibited; and journalists were not allowed to approach the participants.

In early April, Joe Wong Nai-yuen and Denny To Chun-ho—former staff organizers for the now-disbanded Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU)—publicly applied for police permission to organize a May Day march as individuals. They had formal meetings with the police in April, where they were questioned about the details of the march, including how they would “avoid violent groups from hijacking the march.” The organizers responded that they believe that the May Day marches have historically been peaceful in Hong Kong, with no evidence of “violent” groups looking to hijack this event, and that they thought that the police would have the ability to protect a minor demonstration from any disturbances that might occur.

On April 25, Wong was detained incommunicado by the police for a few hours, though he was not arrested. Upon his release, he was reported to be suffering from an “emotional breakdown,” apparently due to having been subjected to immense pressure. Wong informed To that he had unilaterally withdrawn the application for the march, but that Article 63 of the National Security Law, which states that those who “assist with the handling of a [national security] case shall keep confidential any information pertaining to the case,” prohibits him from discussing the reasons.

The two labor activists explained why they applied for a May Day march permit in a Facebook post on April 10, which we have translated and republished below in full. We have also translated and republished Denny To’s follow-up post about their decision under compulsion to cancel the march. Lausan has no affiliation with the writers.

Why we are applying for a May Day march

On the afternoon of April 9, we applied for permission to organize a May Day march as individuals.

Why should we apply to hold the march? Probably no one thought that this would be an issue just a few years ago.

As many know, the celebration of Labor Day on May 1 originated in the Haymarket affair in 1886. US unions launched a general strike on May 1 to fight for an eight-hour work week, and hundreds of thousands of workers took to the streets across the nation. On the evening of May 4, workers held a peaceful rally at Haymarket Square in Chicago. As the police were demanding workers shut down their rally in the name of the law, an unidentified individual threw a bomb. The police subsequently opened fire on the protestors and caused many casualties. The local authorities could not verify who threw the bomb, but nonetheless charged eight organizers for “conspiracy.” Despite not having evidence to prove their complicity, the court still decided to declare them guilty: five were sentenced to death by hanging while two were imprisoned for life. The incident was hugely unjust and led to widespread public outcry. The Second International, which was organized by socialist parties in Europe, declared May 1 as International Labor Day. Since then, May 1 gradually became a significant day for workers’ protests across the world.

We recall this history not just to remember and lament: 137 years today since the Haymarket affair, Hong Kong still does not have a guaranteed eight-hour work day, or even legally-protected overtime pay. Nor are we merely making the point that the banning of protests and rallies by police in the name of “protecting social order,” and the use of the law as a tool for repression, have much historical precedent. Our hope is to illustrate the historical importance of May Day to the labor movement. The labor rights and social security enjoyed by workers in places like Europe today did not simply fall from the sky, but were won by the sacrifices of 200 years of countless workers’ struggles. Today, workers enjoy the fruits—fought for with blood and tears—of the labor movement struggle waged by those who came before us. And we must continue to struggle to protect these hard-won gains. The ongoing massive strike wave for wage increases to counteract the effects of inflation in Britain, and the militant workers’ struggle against pension age reform in France, are examples of this continued fight.

When faced with a ruling class possessing a tremendous amount of political and economic power, workers can only transform an unjust social structure by exerting pressure against those in power through the power of solidarity and self-determination. Some social elites draped in the garb of labor declare that protests are not important, saying that workers have other avenues of “speaking out” and that the government would “heed” their opinions. If changing society is that simple, then we would not have labor issues in this world. Of course, we are not so naive to think that organizing a march of a few hundred participants would create any sort of real strength and pressure to successfully precipitate concrete changes. We all understand how difficult organizing is in Hong Kong today. We understand the challenges and risks even more so after witnessing the recent controversy around applying for rallies in recent months. But it is precisely because it has become so difficult to organize rallies today that people’s attempts to keep on organizing rallies and to assert their right to do so have taken on a new significance.

The social movement is a long and arduous road, and we cannot simply focus on the successes and failures of one particular moment. As we stare down the path trodden by our predecessors in the labor struggle, our successors—in some future space and time—are reviewing the decisions we make today. Every little decision we make today will determine the position from which those who come after us will carry on the struggle. The Haymarket incident in itself did not bring about any concrete gains, and May 1 might have been just another ordinary day. It is the actions of those who came after the Haymarket martyrs who gave meaning to what happened on May 1. The organizers of the future will also give meaning to the actions of organizers today. No matter how much or how little space there is left to organize in Hong Kong today, and how much we can realistically achieve, the most important thing is to continue passing on the spirit of May 1.

Joe Wong Nai-yuen and Denny To Chun-ho

April 10, 2023

About what happened and the decision we were forced to make today

At around half past eleven this morning, Wong Nai-yuen regained his personal freedom. He was not arrested, but had experienced a nervous breakdown, having apparently been subjected to immense pressure. He informed me that he had signed off on the withdrawal of the application for the march permit, but was unable to divulge any more details because of Article 63 of the National Security Law.

We had had some inkling that something like this might happen from the moment we decided to apply for the march. The striking correspondence between what we had expected to happen and what then did happen is no coincidence. Although the present circumstances are extremely difficult, we hope that Hongkongers will continue to stand by the values we believe in. Just as we had said, in our explanation about why we were applying for a May Day march, that the social movement would be a long and arduous road, so must we not overly fixate on a specific moment’s setback or success. When eggs pit themselves against an impenetrable high wall, often there is nothing that can be done. Nobody is a saint, nor can the social movement demand sainthood of any of its participants. The most important thing is not to obey in advance, so long as circumstances permit.

Timothy Snyder once pointed out: “Do not obey in advance. Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.”

We hope that, through our actions, we have heeded these words to some extent. This setback will not diminish our determination to struggle for workers’ rights, and we will continue to work hard alongside our fellow travelers in the days to come. The road ahead is long and strewn with obstacles, but as long as we persist in our march, the bright future that awaits at the end will make it all worthwhile. In any case, we extend our heartfelt apologies to the public, who we hope will treat our decision with understanding and kindness. Thank you!

Denny To Chun-ho

April 26, 2023