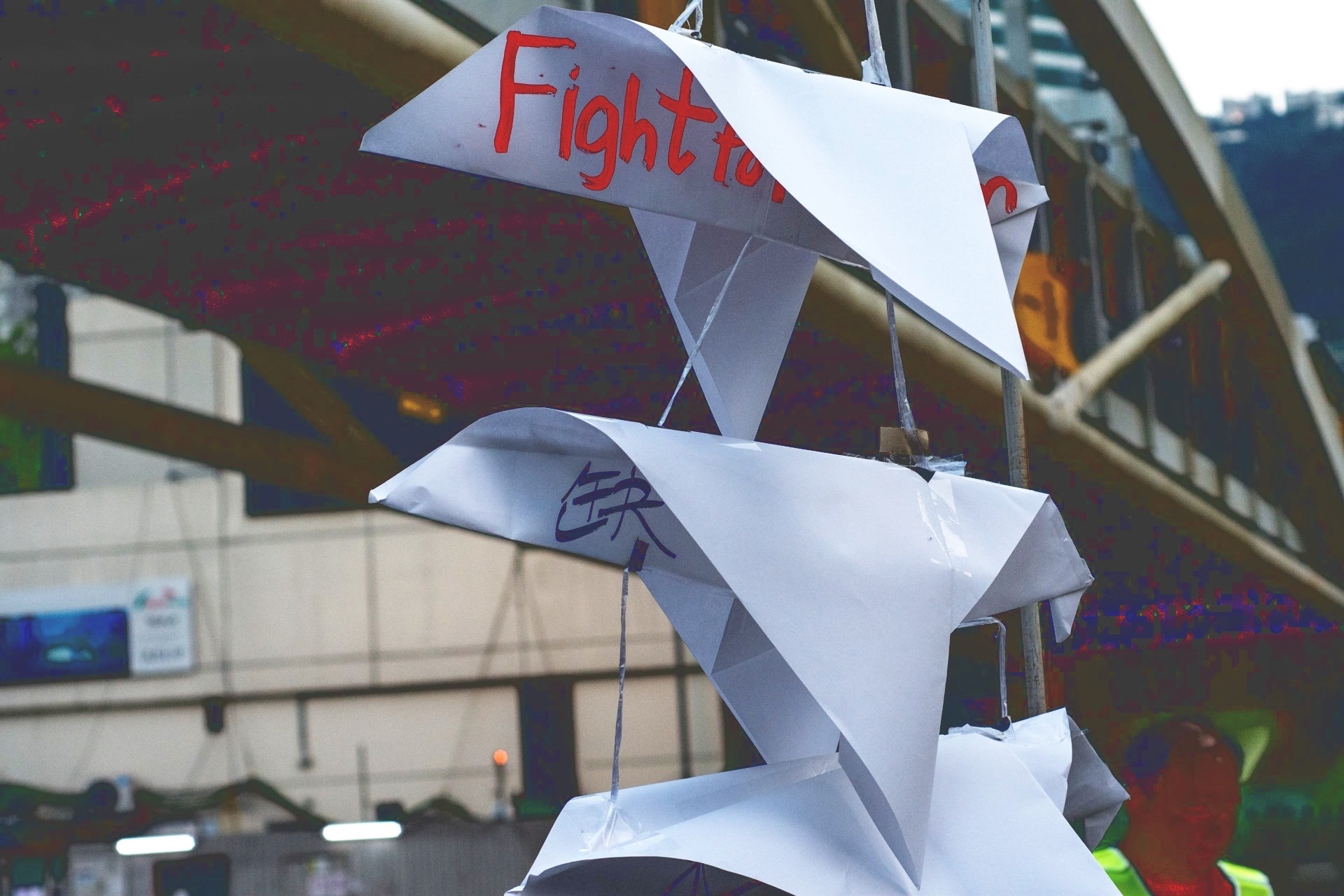

Last week, Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Union (HKCTU)’s leadership announced its decision to disband, spelling the greatest blow to the city’s organized independent labor movement in generations. HKCTU’s fall follows this year’s prolonged and tedious timetable of repression from the Hong Kong government—as it ramps up the persecution of those left opposed to its rule under the draconian National Security Laws (NSL) enacted in June 2020. The NSL was the final nail in the coffin for the downturn of the anti-extradition bill movement that was already severely constrained by early last year after a months-long mass movement struggle against the city’s Beijing-backed political leadership, and further hemmed in by the sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This year has seen a massive and unprecedented clampdown of the city’s weakened opposition, with the Hong Kong judiciary—alongside the prosecutors and the new national security department—casting a wide net that expands week by week. From any isolated individual seen displaying a protest slogan to the leaders of the city’s oldest and most non-militant established opposition groups, like the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China (“the Alliance”)—all are subject to pressure to disband, and directly imprisoned on illegitimate charges.

But HKCTU’s breakup represents a devastating new low in the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) wide-ranging campaign of repression. Since the Handover, Hong Kong’s labor politics have been dominated by the umbrella of unions under HKCTU and those under the larger, pro-Beijing Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU). While the latter boasts a larger membership, with a long history of workers’ organizing since a year before the success of the Chinese Revolution in 1949, its unions are severely depoliticized, with a deep history of undercutting workers’ militant actions in favor of stable labor-management relations. On the other hand, HKCTU has functioned as the backbone of Hong Kong’s independent workers’ politics, acting as its closest ally in organized labor, social movement politics, and even in the electoral realm in the past. While it is not without its structural problems, HKCTU remained the only vehicle of the two federations through which any independent workers’ organizing can be sustainably cultivated. Its repression is sure to further decimate the new union wave that emerged out of the protest movement.

HKCTU’s downfall and HKFTU’s now-complete monopoly on Hong Kong labor politics signal that we must re-evaluate how independent workers’ organizing must be re-envisioned and sustained, which means addressing how the forces of capital and imperialism express themselves in the present: Illiberal authoritarian states that espouse a politically “anti-imperialist” and “left-wing” rhetoric while remaining thoroughly in collusion with the neoliberal global order first shaped by the West. To understand this, we must transparently work through the history of Hong Kong labor politics, as encapsulated in the relationship between HKCTU and HKFTU, and discover its contradictions and lessons. In doing so, we will find that independent workers’ organizing remains at the center of a truly liberatory project for Hong Kong and the global labor movement. We must develop new paradigms for the future from an honest appraisal of HKCTU’s past successes and pitfalls.

Hong Kong’s labor pluralism of the past

Formed in 1990, HKCTU began as a coalition that gathered various grassroots trade unions, left-wing activists, Christian labor associations, and community organizations that were independent of both the CCP and the Kuomintang (KMT).1 Before the Confederation and since 1949, the key actors in Hong Kong’s organized labor were the CCP and KMT’s satellite associations: the aforementioned HKFTU and the Hong Kong and Kowloon Trades Union Council (TUC), respectively. The HKFTU and TUC’s political rivalry, couched in the broader geopolitical tensions between the Communist government in Beijing and the Republic of China’s government-in-exile in the Cold War period, was the mainstay of labor politics. In the 1950s and 60s, Hong Kong transitioned from a small, commercial trading port to an industrial export-oriented manufacturing hub, supported by a massive migrant labor pool from the Mainland in the rising manufacturing sector. After the momentous 1967 riots, the 1970s and 80s saw a new, historic union wave—with the HKFTU expanding their union base and existing majority in the labor movement, while the TUC began their slow decline. From this wave also emerged a new phenomenon: Independent unions in various sectors from social services to teaching and other labor organizations that were unaffiliated with either HKFTU or TUC.

Hong Kong’s economic growth slowed in the 80s, accompanied by parallel movement in real wages. But HKFTU—despite their continued growth and influence—was disinterested in and unable to organize workers against the excesses of the city’s turn to neoliberalism, which was marked by increased wage cuts, rising unemployment, and other issues related to employment security. As Hong Kong’s political future was becoming an uncertain topic, the HKFTU tempered its organizing ethos in the face of the CCP’s turn toward market reforms and the Deng Xiaoping administration’s negotiations with the British government in the Sino-British talks in the 80s. Even in the mid- to late 1970s, as scholar Law Wing Sang reports, pro-CCP civil society organizations were already retreating from militant mass-based organizing after the anti-imperialist movement of the early decade, turning instead toward nationalist education and propaganda work while substituting workers’ organizing with a service-based, welfare model.

At this time, while pro-CCP groups continued propagating cultural work about Chinese nationalism with “Back to China” trips in their ranks, independent labor groups continued to grow in strength, filling the void in grassroots workers’ mobilization in the face of a neoliberal government program. Former CCP member Szeto Wah transformed the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union into the city’s most powerful labor group by the 80s. Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee (HKCIC), while not a union, importantly supported and connected different grassroots unions and workers’ organizations to eventually form what would be one of the main cores of HKCTU (CTU’s key leader, Lee Cheuk-yan, now imprisoned under national security charges, emerged from HKCIC). In this period, other important labor struggles were waged by independent workers organizing against the colonial regime’s policies. These independent workers later became associated with HKCTU, including the civil servants.2

In the meantime, HKFTU would rapidly degenerate further. In keeping with the CCP’s traditional paternalistic politics toward workers’ organizing, and now with a new mandate to ensure the stability of the transitional Handover process to the new regime by the mid-90s, it acted as a reactionary force in labor, substituting the class struggle for “peaceful” solutions with employers by advocating to “work together with all social strata for the progress and stability of Hong Kong,” as one union representative declared in 1985. HKFTU largely abstained from protests by the 1980s, thereby essentially enabling the colonial government’s neoliberal austerity measures. Furthermore, while the central elements of the colonial regime—under pressure from the CCP—worked against electoral reforms for the expansion of Hongkongers’ limited voting privileges, HKFTU actively worked with organized corporate interests, through the Business and Professional Group (BPG), to organize against universal suffrage. The federation infamously organized workers away from electoral reform under the slogan “Yes to rice coupons! No to ballots!” (寧要飯票,不要選票!). Its consistency in depoliticizing and rejecting workers’ demands did not go unrecognized by workers: In December 1989, over 200 bus drivers under an HKFTU union resigned in protest of the union’s conciliatory attitude toward their employers.

HKFTU actively worked with organized corporate interests, through the Business and Professional Group (BPG), to organize against universal suffrage. It infamously organized workers away from electoral reform under the slogan ‘Yes to rice coupons! No to ballots!’ (寧要飯票,不要選票!)

In this climate, HKCTU was formed as an alliance of the diverse elements from the labor struggles of the past decade, combining rank-and-file organizing with legislative advocacy. Throughout the 90s, the HKCTU allied with a newly-formed opposition camp, alongside the United Democrats of Hong Kong (the Democratic Party after 1994) and other organizations, fighting for the city’s collective bargaining rights for the first time on the eve of the Handover. This alliance, as HKCTU Vice-Chair Leo Tang noted, has its costs. In recent years, HKCTU was:

simply reduced to representatives of the pro-democracy camp by the public (despite its intention to be a representative of workers)… As such, whenever the unions try to represent the ‘pro-democratic voice of workers,’ they are destined to be sidelined by the already bureaucratized pan-democrats―from whom they never cared to distinguish themselves.

Without a strong labor movement outside of legislative advocacy work, any pro-worker gains were immediately reversed by the Beijing administration within weeks of taking over, and the dynamics between HKCTU and HKFTU solidified into a relatively stable rivalry that continued up until the 2019 movement. The new Beijing-led Hong Kong government revised labor laws to end workers’ right to collective bargaining in 1997, an initiative that HKFTU representatives on the LegCo either voted for or abstained from. Building from its class-collaborationist program developed in the late-colonial period, HKFTU—now the state-backed union coalition—has become perhaps one of the most effective company unions of its kind. Boasting the largest membership size, the HKFTU has been a central vehicle for the CCP to divide the workers’ movement, using state resources to pacify and depoliticize workers under its wing while the Party courts the power of local and foreign corporations to challenge the US for hegemony of the global neoliberal order.

Monopolizing the Labour functional constituency seats in the Legislative Council, HKFTU and its government allies have organized for all kinds of anti-worker policies. After the Handover, HKFTU has repeatedly fought against HKCTU and other allies’ attempts to push for workers’ collective bargaining rights. In the 2000s, HKFTU advocated for further reducing workers’ protection on the controversial gentrifying Shenzhen-HK rail link project, arguing for a lower minimum wage, opposing paternity leave and social services for the disabled, breaking strikes, undercutting wage increase demands and supporting the state’s various privatization schemes. Rank-and-file Vitasoy truck driver organizer To Chi-kuen recalls that it is commonplace for his colleagues on the shop-floor and other workers to recognize that HKFTU “doesn’t have workers’ interests in mind,” and turned to HKCTU to build their strike in 2008. Similarly, in 2013, dockworkers in HKFTU grew disillusioned and turned to HKCTU and other civil society groups for support to launch the historic dockworkers’ strike. During the anti-extradition bill movement, HKFTU publicly committed voter fraud, hiring buses and paying citizens to vote for their district council candidates—an electoral struggle that the pro-Beijing camp lost in a significant landslide. Over 140 HKFTU-affiliated Jockey Club workers released a statement declaring that “our union does not represent us,” and Stand News reporters later revealed that HKFTU, threatened by the historic rapid growth of independent unions during the movement, registered fake unions to match HKCTU’s incorporation of these new, politically-engaged unions from over 60 new sectors.

From the dockworkers and Hoi-lai cleaning workers in the 2010’s to the new unions of the protest movement, HKCTU has consistently provided support for independent workers though, of course, it is not without its problems. It has openly received NED funding—a US-backed institution associated with many destabilizing US imperial initiatives in the global South—but one’s legitimate criticism of such collaboration must also take into account HKCTU’s embattled position in Hong Kong civil society, where workers’ politics have long been divided and demobilized by the CCP, and where there is minimal government support. The charge of foreign interference extends beyond HKCTU too. The same source of “dark” funding from the NED that the CCP is charging HKCTU for receiving also funded pro-Beijing groups’ programming—the same groups gleefully cheering the demise of their once fellow recipients. In addition, the annual NED sum, divided between an unspecified number of labor organizations in Hong Kong, is meager; enough to help with some unions’ operational costs, but, in effect, far inferior to the CCP’s large-scale links with Western capital to suppress workers.

The CCP’s hypocritical charge of the HKCTU as “foreign subversion” demonstrates the bankruptcy of its so-called “anti-imperialism,” which loudly trumpets anti-imperialist aesthetics while obscuring the CCP’s own collusion with the global imperial order. In a sense, HKCTU’s own weaknesses—its bureaucratic nature, its gap between staff organizers and workers, and its difficulty in cultivating and sustaining rank-and-file leaders and movements in and across the workplace reveal not its unique sin, but a symptom of the decades of workers’ depoliticization under colonial and CCP rule. Rather than condemn and distance ourselves from what was the only avenue for organized labor to support independent workers’ struggles, we must note how the impoverished and resourceless environment for workers that Hong Kong’s sovereigns have cultivated has necessitated such unfavorable political decisions.

Planting seeds for future labor struggles

Beijing, whose thorough integration with the global financial order has buttressed its police state infrastructure, has long had vested interests in demobilizing independent workers’ organizing.3 As a nominally “Communist” state, it is more sensitive toward winning workers’ support than Western “liberal” regimes, which requires disempowering their class independence through collective action by at least upholding a pacifying, though eroding, safety net of occasional social welfare reforms. The CCP also understands that the only way in which its power can be challenged en masse is not through an isolated Hong Kong independence movement, nor the lobbying efforts of anti-communist diaspora dissidents, but the power of everyday workers to connect across the workplace and borders to counter its deep reach at the point of production.

Along with the widespread repression of all aspects of civil society, the fall of HKCTU and HKFTU’s now-complete monopoly on labor politics signals that the CCP seeks to disallow all organized vehicles for independent politics. In other words, the international left and labor movement’s usual paradigms for independent labor have become unavailable in Hong Kong. Like in the Mainland, any glimmers of independent organizing beyond containable spontaneous and ephemeral direct labor actions are illegal. This is not even to mention the prospects of building union reform caucuses, transitional organizations, and other formations to assist and support independent workers’ politics from the outside, or any left-wing agitational groupings that aim to develop a mass base from rank-and-file struggles.

What is to be done in such a bleak political climate for labor and democratic movements? The left has never developed a strategy for how to organize a mass movement in a “left-wing” regime. Strictly speaking, no Communist state has ever been directly toppled by a revolutionary mass movement in history. In a globalized world where the power of capital not only extends through Western liberal regimes, but also unevenly through illiberal states of the Global South, we need new paradigms for change that are still grounded in the potential of independent workers’ organizing. Hongkongers must lay low to continue political education and agitation where we can, from developing informal study cells to hone our politics and share organizing experiences to taking up work in strategic industries central to Hong Kong’s economic power levers. We must also continue to rethink and energize the role of the diaspora.

Instead of the conspicuous actions of 2019-2020, the struggle must continue in a new phase, strategically laying the seeds for the next generation by understanding that our fight in Hong Kong does not end in exile, that our disenfranchisement and oppression exists in the intersection of inter-imperial rivalry and collaboration, rather than a simplistic Cold War conflict between “freedom” and “authoritarianism.” The concluding sentence in HKCTU’s statement to disband shows us the way forward: “The flowers fallen are not the flowers heartless; as they become soil in spring, they nourish yet more flowers.” HKCTU’s departing staff recognize that as much as it has been pivotal in supporting independent workers’ struggles over the years, the spirit of independent unionism means that independent workers’ politics are never simply reducible to HKCTU. Where there are workers, there will be struggle—there we will find the legacy of HKCTU.

Footnotes

- Some of the materials in this section are adapted from Stephen Wing-kai Chiu and David A. Levin, “Contestatory Unionism: Trade Unions in the Private Sector,” in The Dynamics of Social Movements in Hong Kong, ed. Stephen Wing-kai Chiu and Tai-lok Lui (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2000).

- See Hong Kong labor researcher Leung Po-lung’s new book, 政府內部的吶喊:香港公務員工運口述史 (新銳文創, 2021), for a collection of oral histories related to the civil servants’ activism in the 80s.

- See Michael Dutton, Policing Chinese Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005).