Last month’s murders of Asian women massage workers in Atlanta marked another devastating milestone in a recent wave of anti-Asian violence fuelled by pandemic racism and the Trump administration’s Sinophobic rhetoric in its rivalry with China. With a hardline stance against China becoming, as one pundit quipped, one of the few major bipartisan issues left in Congress, leftists and progressives have seemingly been issued a stark ultimatum: condemn the crimes of the repressive Chinese Communist Party (CCP) at the risk of fanning the flames of a “new Cold War,” or highlight US aggression against China at the expense of providing solidarity to Chinese workers and dissidents.

The lack of a coherent alternative to this double bind has provided the perfect opportunity for pro-CCP “left” and “anti-war” groups to merge their discourse with a revived but contradictory Asian American anti-racist movement. Many leftists in the West (including Asian Americans) have justified their silence toward Chinese dissidents by bastardizing the concept of a people’s right to self-determination. They argue that Chinese people should be left to manage their own contradictions and struggles—thus conveniently reducing the diversity of these lived experiences in the mainland and in the diaspora. This perpetuates the monopolization of Chinese identities by the Chinese state.

The US anti-war position has largely been defined by the ANSWER Coalition, which has held a virtual hegemony over the US anti-war movement since the Iraq War by neutralizing the space to organize against imperialist aggression by those states they view as “opposed” to US empire. Predictably, their response to the rise of anti-Asian violence was to organize a national day of action that conjoined “Stop Anti-Asian Violence” and “Stop China-bashing” into one slogan. While combining these messages may seem innocuous, in reality, conflating violence against Asian people and state-level conflicts impedes the struggle against Sinophobia and racism by furthering the artificial geopolitical conflict between US and Chinese elites, and pitting regular Asians and Asian diaspora against one another.

In effect, what appears to be a soft consensus among these two broad mobilizations against anti-Asian violence to narrow our focus solely on US aggression has only strengthened the position of apologists intent on weaponizing this moment of crisis to neutralize critique against the CCP. While these various groups offer only a binary choice, a narrowing of options amidst increasingly strident Cold War rhetoric, the left can and must provide concrete alternatives that resist harm of all kinds against Asians everywhere. This must entail rethinking how anti-CCP organizing in the diaspora has long been framed: We must instead emphasize internationalist demands that can account for the interconnections between the repressive engines of the US and the CCP by bridging various anti-capitalist, anti-authoritarian, and anti-racist struggles from below.

This is not the time for unity

Just as the demonization of the Chinese state alongside its people contributes to racism in the West, the erasure of Asian and Asian American voices resisting CCP state repression reinforces its own kind of violence. This lack of nuance in accounting for diverse perspectives limits our horizon in organizing Asian communities against interconnected networks of systemic violence. Trump’s efforts to target international students last year placed hundreds of thousands of Chinese, Hongkonger, and other Asian American students in a dangerous position: from fear of political repression to other forms of prejudices associated with both pandemic restrictions and other social injustices, many of these students would have been deported back to a home in which they feel unsafe and unwelcome.

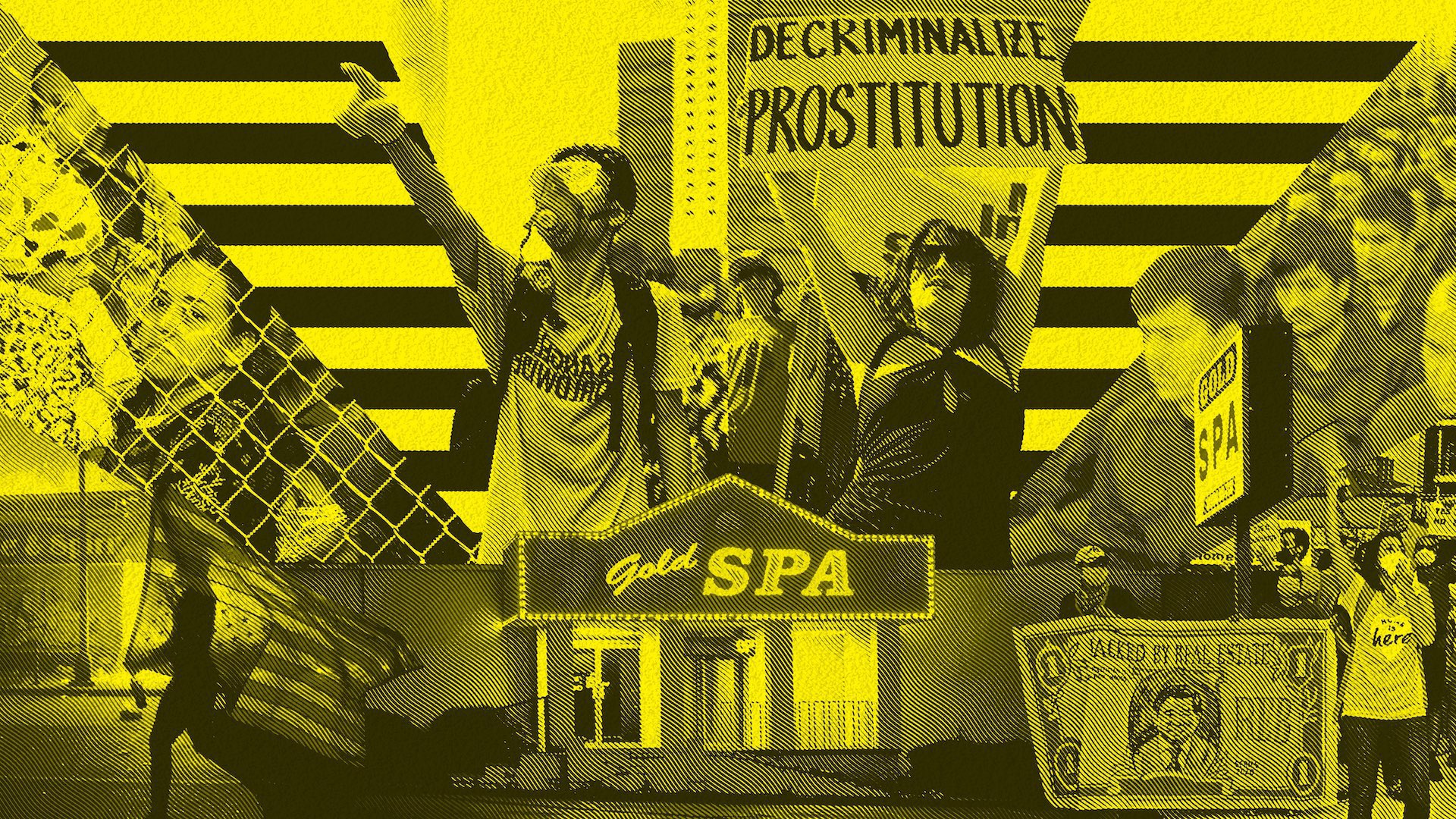

In a globalized system of anti-Asian violence, one cannot compartmentalize anti-racist struggle within the national boundaries of certain states. The Atlanta shootings remind us that massage and sex workers—many of whom are Asian migrants—have long been stigmatized and criminalized by draconian anti-sex work agendas inherent in legal frameworks from the Chinese hukou system to US anti-trafficking legislation, often spurring them into a circuit of displacement and migration from Hong Kong to New York. The CCP’s program of repression against majority-Muslim Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in “Xinjiang” borrows from US counterinsurgency and policing methods, thus reinforcing its own regime of anti-Asian racism as it connects to Islamophobia. Chinese state-owned capital, in collusion with local city government and transnational corporate developers, has also been at the forefront of propelling gentrification in Asian American enclaves like Flushing. These instances of structural oppression against Asians and Asian diaspora are swept under the rug in a framework that conflates all criticism of the CCP with racist “China-bashing.” This confusion testifies to the reality that the fight against anti-Asian violence is one that must require ideological distinctions, by out-organizing and resisting those among our communities who merely uphold one system of oppression over another.

In a globalized system of anti-Asian violence, one cannot compartmentalize anti-racist struggle within the national boundaries of certain states.

The Asian diaspora community’s inability to organize around a radical critique of the CCP in light of the complexities of US-China tensions and the reality of anti-Asian racism is a symptom of a larger problem: That anti-Asian violence has created a discursive atmosphere in which working through contradictions within our own communities is seen as a position of privilege or even harm, rather than a necessity for collective liberation. In this sense, Asian diaspora liberals’ and conservatives’ demand for more policing and pro-CCP leftists’ uncritical defense of Chinese state violence can be seen as two sides of the same coin. In the wake of the Atlanta murders, this is not the time for unity: We must demarcate political lines within our communities to hold accountable Asians and Asian Americans (be they celebrity or business elites) who have upheld exploitative systems, and genocide deniers and other apologists of state terror, who value certain lives over other marginalized ones in our communities.

At the same time, the difficulty in separating congressional “tough on China” policies and Sinophobia should be a wake-up call for the dominant infrastructures of anti-CCP organizing in the West, especially from the Hongkonger, Taiwanese, Uyghur, Tibetan, and other dissident diaspora groups. By exceptionalizing the CCP’s crimes and refusing to acknowledge how the very same systems they have appealed to for aid have helped build the mechanisms of Chinese authoritarian state capitalism, diaspora groups have willingly allowed the imperialist US establishment to contain our terms of struggle, distorting the path to liberation. Indeed, Hung Ho-fung is right to note that we must not “forfeit […] critical stance on actions by China’s government on national security and human rights issues because we fear a backlash against Asian-Americans,” but he is incorrect to note that our strategies should be dependent on “the consideration of U.S. national interest.” Hung neglects to criticize how Hongkongers’ dominant mode of anti-CCP advocacy in recent years is incompatible with a genuine movement against systemic anti-Asian violence. His oversight is representative of a significant political limitation in contemporary diaspora anti-CCP organizing more generally: The fight against the CCP cannot be conducted without reckoning with the systematic injustices of US imperialism, and this means we must radically rethink how we have conducted our international lobbying up to this point. These new paradigms must emerge from deepening exchanges, not forcing wedges, between existing organizers in the struggles against CCP violence, US imperialism, and anti-Asian racism.

An alternative coalitional politics

In reality, many Asian diaspora organizers who are critical of the CCP have been at the frontlines of organizing against anti-Asian violence and US imperialism—through tenant organizing, sex workers’ advocacy, workers’ movements, among others. Neglecting these interconnections in political work not only further endangers the safety of Asian diaspora organizers, but limits our capacity to promote systemic change. As a Chinatown tenant organizer and part of the Hong Kong and Chinese diaspora, I feel unsafe being compelled to join a united front with activists and organizations (like groups associated with ANSWER) that advocate for people like me to be detained—or worse—in my home city. Does the movement against anti-Asian violence in the diaspora not have room for such lived experiences and perspectives?

And yet an alternative kind of coalitional politics is already developing in the diverse ecosystem of organizers who refuse to see abstaining from critique of the CCP as a solution to the violence in our communities. Organized Chinese diaspora feminists insist on organizing strategies that stress cross-border and progressive actions on the frontlines without having their “political position defined by the Chinese government.” Los Angeles-based pro-democracy diaspora Hongkonger organization Hong Kong Forum condemns the long history of violence against Asian Americans while “join[ing] our allies to fight against discrimination” and seeking to “empower ourselves and learn Asian American’s history adequately.” Some Uyghur and Chinese Americans advocated for joining their causes against the CCP with the ongoing fight against anti-Asian racism in a recent rally in D.C., while signaling solidarity with sex workers, Black, Indigenous, and other people of color alike.

With this key goal of raising independent political awareness and building coalitions from below among movements in mind, it is also time for a concrete set of foreign policy alternatives that can hold accountable the systems of repression that mutually reinforce one another between the US and Chinese nation-states, beneath the loud rhetoric of the “new Cold War.” As Dai Jinghua reminds us, “the new Cold War” framing often obscures the globalized framework of capitalist exploitation of marginalized communities, such that “neither China nor the US can… proffer any choice of path outside of global capitalism or any plan to resolve it.”

Tobita Chow and Jake Werner offer useful starting points in their framework of “progressive internationalism”: raising international demands for better standards and accountability around labor rights, migrant justice, and climate change—all of which directly call attention to long-standing collaborative relationships that bolster the repressive powers of both the US and China. This can shift the framing away from “tough on China” policies that entrench racist sentiments against Asian peoples and reinforce a geopolitical struggle that benefits no one but the elites, while also striking at the weak points of nation-states that uphold interlocking regimes of violence against Asian communities globally.

These strategies at global systemic reform and accountability may ultimately be unreachable in the long run, but they can pave the way for transitional demands that drive the inherent contradictions of the global capitalist system out into the open. We can do this all while strengthening the political power and organizing capacity of masses of ordinary people, especially Asians and Asian Americans caught in the crossfire of white supremacy, great power conflict, and capitalist exploitation. We must resist those in our communities who weaponize these deaths as a political bludgeon in service of another purveyor of violence against Asians, just as we combat those who use this moment to stoke anti-Blackness and call for more policing. And this must happen without letting the movement against anti-Asian violence become yet another bargaining chip between two repressive super powers.