A “SARS outbreak” on the mainland was first reported by media in Hong Kong on December 30, 2019. For those living in or involved with politics in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China, the past year and a half has meant being subjected from all sides to a seemingly endless torrent of conspiratorial, reductive analyses of China’s “totalitarian and dystopic” Covid response. For Hong Kong, this developed out of unique circumstances: Covid arrived after 6 months of turmoil and non-stop protest in the streets, online, and at home. At the same time, as many protesters began to reassess strategy or simply burned out, the pandemic upended everything by investing the government with renewed “neutral” public health authority to control public gatherings and social behavior. For many youth protesters, who were already facing trouble for their radical “yellow” politics from “blue,” pro-police or pro-government parents, a tense home life or even homelessness became existential threats during a pandemic.

The distrust of the government and antipathy towards increasingly hardline police soon shifted gears as those same repressive, bureaucratic forces mismanaged pandemic resources and withheld information about Covid response from the general public. Hong Kong people’s much-lauded grassroots response (thanks in part to prior experience with SARS in 2003 but sharpened to a point through anti-government mutual aid during the 2019 protests), was swift and many credit the successful containment of Covid in Hong Kong not to the government but the general population’s voluntary participation in public health best practices.

Yet the government’s bad faith response, particularly Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s opaque statements and arrogant attitude at press conferences, and Hong Kong people’s understandable snowballing distrust of present authorities, also created the conditions that furthered the growing commonsense perception of an omnipotent Chinese state, one that responded to Covid containment and political resistance with equally monolithic and fetterless power. In other words, 2019 saw popular conceptions of China in Hong Kong rapidly exaggerate long-simmering distrust of the Chinese state into caricature, due in large part to the CCP’s own blustery claims to totalizing supremacy.

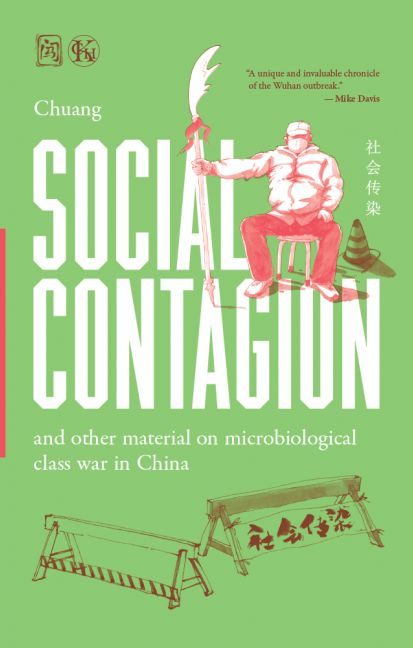

Into this fray, Chuang’s widely-circulated 2020 essay “Social Contagion: Microbiological Class War in China” arrived like a beacon, with its materialist contextualization of not only Covid in China but the social and political circumstances of the pandemic’s planetary impact. Chuang’s greatest strength is in writing communist critique that takes Marx’s materialist method seriously in analyzing China’s socialist developmentalism and its transition into capitalism in their influential essays such as “Sorghum and Steel” and “Red Dust.” This requires an understanding of history not as a self-apparent script that we read from in order to validate our interests in the present but as a set of evolving social relations that allow us to trace and make determinations about the rationale and accuracy of people’s present-day analyses, statements, and actions—whether that be the Party, workers, local village elites, US news media, politicians, academic ideologues, or the online commentariat. Public discourse regarding Covid has gotten progressively worse since the essay’s publication, with disinformation campaigns and lab leak theories reaching wide distribution, which has furthered the conspiratorial discourse against China as a civilizational enemy. These dire conditions make Chuang’s book Social Contagion: and other material on microbiological class war in China (Charles H. Kerr 2021), including a revised version of the titular essay, all the more critical.

Social Contagion puts forward two main interventions: One is to undo the mythical notion of the Chinese state as a “Neo-Confucian Leviathan” by analyzing “the capacity of the state and the nature of its response to the pandemic.” Chuang argues that the popular conception of a totalitarian China having successfully contained Covid through authoritarian means obscures the fact that China did not, in fact, contain the virus but disastrously botched it due to the bungling and obsequious response of local authorities. Yet the idea of successful containment through authoritarianism maintains its currency both in China and the West: For the former, it vindicates statebuilding founded on a strong centralized state apparatus; for the latter, Cold War anti-communism positions China’s victory in fighting Covid as an immoral and barbaric trampling of individual liberty to be avoided at all costs.

Against this shared discursive delusion, Chuang historicizes the development of what they call “the floating state,” which they describe through the metaphor of the Zhou dynasty pontoon bridge: The imperial court is the bridge, the local officials are the pontoons, and the water is the people. The emphasis here is on the critical function of the local gentry who both facilitate interaction between the imperial court and the people, and, when done in enough numbers, can also facilitate people’s revolt. This relationship between the emperor, local authorities, and people was an important part of dynastic statecraft but also more general conceptions of social relationships altogether. Chuang argues that the state’s “floating” nature is a thread that can be drawn forward from the dynastic, to the socialist developmental and reform states, and finally through to the present post-reform era.1 The exact configuration of these various pieces appear differently in each period based on the political philosophy and social and material conditions of the time, but what is important to hold onto is that the development of the Chinese state is a history of fragmentation based on a constantly shifting calculus of local autonomy as it assists or resists central authority, and it is precisely this fragmented arrangement, not a transcendent, omnipotent Central Government, that was forced to respond to Covid. For China, however, post hoc renarrativization of local autonomy and grassroots action into part of the Party’s grand plan is common practice. As Chuang reminds us, “Every weakness is, after the fact, claimed as a strength.”

Chuang takes an unromantic view of the reality of a fragmented Chinese state, neither insisting that this fact offers an immediate political program for proletarians nor that such fragmentation totally forecloses political action. Rather, the almost countless levels of local autonomy, from village elites to various autonomous policing authorities, that exist below the central bureaucracy means that tactics and chances for victory of organizing and resistance are highly contingent on the most specific local and regional contexts. This is most visible in the highly fragmented nature of regional police forces, many of which operate independently of larger national bodies, and like officials in “Xinjiang” and Tibet, test-run repressive technologies in their own jurisdictions before they are implemented in other regions. Likewise, for proletarians, the scattered and varied nature of workers’ experience—from the mass of migrant laborers to the urban white-collar worker—means that organizing during the pandemic was either nonexistent, easily subdued or fleeting due to the material exigencies of survival during the pandemic. Community mutual aid (a term that Chuang uses to describe community cooperation during lockdown but takes pains to distinguish from Western leftist uses of it as an anti-statist, political tool) was also either temporary, easily reincorporated or commodified, or never had political intentions in the first place.

The other intervention involves the necessity of addressing every scale of crisis caused by capitalism, from the microbiological scale of viruses to the sociological experience of the worker and the planetary scale of climate change. In their words:

[The] communist method of inquiry cannot be reduced to purely economic critique or even radical worker inquiry, but must instead offer a broad understanding of capitalism as an expansive social system that has transformed the anthropological coordinates of human life and devastated the ecological substrata of the biosphere and which now threatens the climatic system of the entire planet.

This method transcends the common nationalist finger-pointing that has come to characterize official and popular concepts of the “origin” of Covid, but also goes beyond indicting a vague and abstract “capitalism” by identifying instead the common capitalist practices necessary for participation in the global market. This is not a novel argument, as Chuang is quick to point out, given that they draw heavily from the work of radical epidemiologist Rob Wallace, alongside Mike Davis, and others.

The book is broken into 4 chapters: The first is a revision of the essay of the same name that moves beyond many of the most simplistic popular commentaries on Covid in China, such as the now-common critique of capitalism’s culpability in fomenting our current plague (indeed, what is capitalism not culpable for today?), asking instead “how, exactly, does the social-economic sphere interface with the biological, and what lessons might we draw from the entire experience?”

The middle two chapters provide granular details on what has thus far largely been represented in opaque and vague terms of “authoritarian lockdown.” Chapter 2, “Worker Organizing Under the Pandemic: A Report by Worker Study Room,” is a translation of an anonymous article by mainland left workers from May 2020. It systematically details the impact of Covid on workers throughout the different stages before and after lockdown from a leftist perspective. The chapter details how the unique trajectory of pandemic crisis in China, including the quicker containment of the virus, has, in fact, led to more muted worker organizing and deteriorating conditions that are often more exploitative than before, including lower income and job security and increased hours, difficulty, and precarity. In sum, capitalists and the government have used the pandemic successfully to further constrain worker organizing but, the anonymous writers insist, the urge to fight remains despite uncertainty about tactics and conditions going forward.

Chapter 3, “As Soon as There’s a Fire, We Run: An Interview with Friends in Wuhan,” is a rich conversation with Chinese activists who experienced the chaotic lockdown in Wuhan, and provides important ethnographic detail that belies what was a common narrative of the Central Government’s immediate and effective authoritarian response to the virus. What these anonymous interviewees reveal is a patchwork of autonomous local authority (autonomous often to the point of disarray) that operated prior to and outside of the Central Government’s own lack of transparency and decisive action. Moreover, they highlight the experience of fear and uncertainty in the gap between official commandments and how people respond to them in practice. As elsewhere, rules are only as good as those who will follow and enforce them. This chapter is particularly important since, as Chuang points out, Anglophone media frequently chooses to platform liberal dissident Chinese voices such as the author Fang Fang (whose Wuhan Diary went viral during lockdown in China and was translated at lightning speed by major US publishing houses), because of the political utility of their limited and liberal calls for freedom of speech and an end to censorship.

Chapter 4, “Plague Illuminates the Great Unity of All Under Heaven: On the Coming State,” is a sweeping analysis of Chinese state-building that contextualizes what mechanisms of governance were available in the present to confront Covid. The main goal is to dismantle the common narrative of an all-powerful totalitarian Party-State. By historicizing the political economic transition from the socialist developmental state to the current bureaucratic capitalist state structure, and in particular by delineating the continuity of political philosophical thinking on local autonomy within different forms of state configuration, the chapter shows why the success of containing Covid in China was due not to transcendent state power, but quite the opposite: informally delegated authority to local committees and grassroots volunteerism. They conclude the chapter by analyzing how state-building under Xi may proceed as “the coming state,” arguing forcefully that China’s transition into capitalism and its context specific development of mechanisms for continued accumulation must not be read through Euro-American political categories lest they obscure a proper understanding of the state that must be resisted. Rather they insist that China’s unseen innovations in capitalist brutality must be studied in their own right.

While Chuang provides the necessary research to inform concrete proletarian planning for future struggle, one also wonders what all this means for the alleged “New Cold War.” This question lies outside the scope of Social Contagion (and has been addressed in their other works such as The Divided God). Yet, as the past two years have shown, the civilizational has become the frame through which everything from Covid to trade to dissent has been framed in US-China tension. An epilogue on political and tactical considerations would be welcome alongside the characteristically poetic “surreal war” that Chuang proposes to meet their grim prognostication of a coming storm.

There is also another topic that needs to be addressed more directly in the context of contagion and capitalist pandemics: The theory of “ecological civilization,” which China adopted into its constitution in 2012 and is thus a key element of how the Party conceives of statebuilding and its relationship to global discourses of ecological crisis. The need for this critique is all the more pressing because Monthly Review, which has built a name on editor John Bellamy Foster’s eco-Marxist writing and influential metabolic rift theory, is an outlet that one would expect to offer a stringent assessment of China’s role in climate change and pandemic. Not so, as the magazine has recently taken a turn toward full-throated apologism for the CCP, resulting in Bellamy Foster himself issuing soft-shoe commentaries on China’s adoption of “eco-civ.” This is all the more baffling, as Monthly Review has proven it is capable of offering compelling eco-criticism: Its press imprint published Wallace’s Big Farms Make Big Flu, which Chuang cites at length as the backbone of their analysis of the political economic and microbiological causes of our current crisis.

If we take the now standard call to action of US socialist ecocriticism to heart, that our present disaster is truly planetary in proportions and requires direct action that transcends all of our present social and political norms under global capitalism, then we cannot let either moralism or these acts of acquiescence by omission continue to shape our critique and action.

This contradiction is not limited to Monthly Review but rather representative of gaps and silences in US-based socialist ecological critique. Perhaps the popular argument—that Euro-American industrial nations have historically contributed more C02 and are thus morally and politically on the hook for more emissions reduction—can be chalked up to a healthy breadth of analysis and diversity of tendency amongst the left. But claims that China’s emissions are in large part a result of being an export-oriented economy (and thus China’s emissions rightfully “belong” to importing nations) sidelines the fact that China is also offshoring its emissions outside its own borders through growing imports from elsewhere along their global Belt and Road supply chain.

This line of argument often leads straight back into the idea that industrializing nations, especially those that have suffered at the hands of Western imperial powers such as China and India, have the moral right to catch up by freely building their productive forces. But if we take the now-standard call to action of US socialist ecocriticism to heart—that our present disaster is truly planetary in proportions and requires direct action that transcends all of our present social and political norms under global capitalism—then we cannot let either moralism or these acts of acquiescence by omission continue to shape our ecological critique and action. The difficulty in accurately understanding China’s role in planetary ecological crisis is due in part to the constraints of an anxiety that doing so will simply let the US and other Western countries off the hook, which is merely the symptom of a larger problem: The US left lacks an unidyllic framework through which to confront the troubling aspects of China’s role in planetary capitalist crisis altogether, one that would effectively open pathways for truly global proletarian revolt. This is a weakness we must face head-on—not least for the masses of climate refugees already trying to escape the ruinous aftereffects of this game of catchup.

Nevertheless, Social Contagion is a model of communist critique that must be adopted in this era of decline and disaster. For those invested in Hong Kong politics, this book’s convincing dismantling of China’s Leviathan can also be a powerful antidote to political despair in the face of a totalizing global superpower. Yet, while revealing the fragmentary and often incapable nature of the Chinese state may seem to open space for further resistance, it may result in the opposite as well. So much political affect has been invested in the idea of singular targets, vested with the totalizing power of the authoritarian state. How do we strategize and find the proper targets when resistance dissipates across a thousand levels of local authority? The answers will be found in the struggle.

Social Contagion also does critical work in compiling evidence to illustrate the separation of the state and the people, a fact that has rapidly fallen out of view in the face of a rising tide of ethnonationalism, and against Party-State claims. The book’s middle chapters provide illuminating detail on the social element of the mainland Chinese experience under lockdown, which holds the possibility of opening avenues for cross-border identification and solidarity. In response to state incapacity, both Hongkongers and mainlanders engaged in grassroots improvisation and various forms of “mutual aid,” though of different sorts. This may seem trite in the face of the challenges that face both Hong Kong and China but given the cultural polarization driven by the Hong Kong government’s lack of transparency and autocratic governance—the city’s own homegrown social contagion—the possibilities of community cooperation as a shared value amongst both Hongkongers and mainlanders is something to hold onto and build from as we pick our way through the rubble of global catastrophe.

Chuang is an international communist collective that publishes an eponymous journal and blog featuring interviews, translations and original articles about China, all rooted in on-the-ground research. Best known for their reports on ongoing class struggles in China as well as influential economic histories of the socialist era (“Sorghum & Steel”) and reform period (“Red Dust”), the collective’s work has a wide-ranging influence on critical social theory, China scholarship, and within the international left.

Footnotes

- Isabella M. Weber has also examined the unique influence of dynastic political philosophy (such as Guanzi) on Chinese statebuilding to explain how and why the CCP rejected neoliberal shock therapy in contrast to their post socialist peers. See Weber, How China Escaped Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate.