Guldana Salimjan is the Ruth Wynn Woodward Junior Chair at the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies department at Simon Fraser University. She is the co-director of the Xinjiang Documentation Project at the University of British Columbia, and the founder of the media art project Camp Album. She also writes under the pen name Yi Xiaocuo (一小撮). Her research has been published in the journal Central Asia Survey, Asian Ethnicity, Human Ecology, and Made in China. She has contributed a book chapter in Creating Culture in (Post) Socialist Central Asia, and the volume Afterlives of Chinese Communism: Political Concepts from Mao to Xi. Her translation of Kazakh short stories have been published in the volume Chinese Women Writers on the Environment: A Multi-Ethnic Anthology of Fiction and Nonfiction.

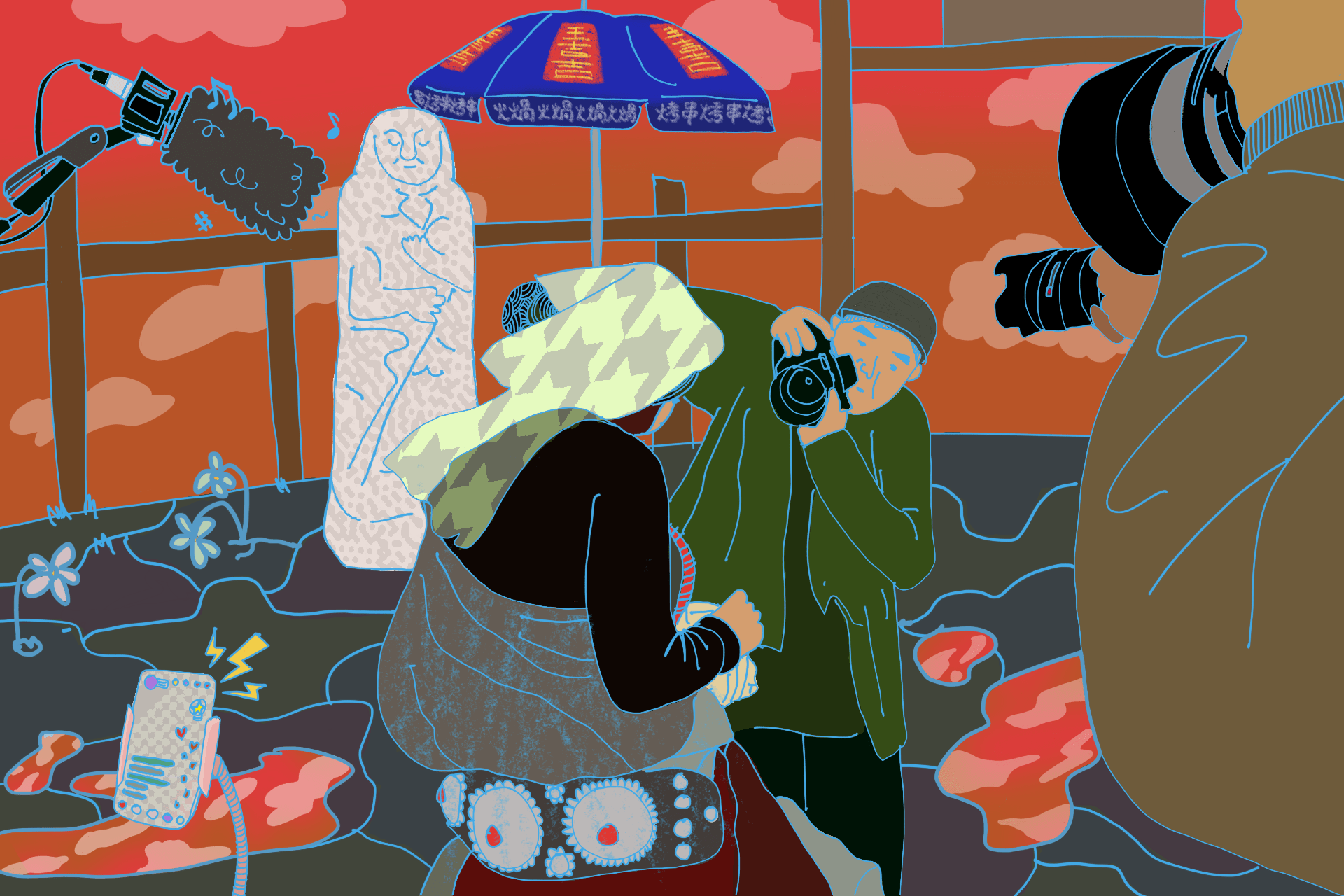

On a summer day in 2015, at Tianshan’s Bogda Lake with a friend who came to visit Xinjiang, I felt out of place in my homeland. On the bus terminal by the lake, which Chinese tourists refer to as Tian Chi (天池) or “the basin of heaven,” the tour guide drew upon romanticized cultural stereotypes to introduce my people to the tourists. “The Kazakhs,” she said, “are nomads who move the most in the world” (世界上搬家最多的民族). Ironically, in the past decade, Kazakhs, along with many other mobile pastoral groups in China—Tibetans, Mongols, Kyrgyzs, Tuvans, and Ewenks—have been pressured by the central government to give up their pastoral life via policies that call for “returning the pastures to the grassland” (退牧还草). Once we got off the bus, I was greeted by a sign that read, “Kazakh ethnic culture garden,” behind which stood dozens of yurts tightly packed against one another. At the entrance of this “garden,” there was a cross section of a yurt beside an eagle and several balbal statues;1 Kazakh and Uyghur dancing costumes hung on the yurt wall for tourists to be photographed in. As I was taking in this Disney-fied display of Kazakh nomadic culture, a group of Kazakh locals approached the tourists getting off the bus and asked them if they’d like to stay for a night in their yurts. I realized at the moment that this was their job—to conduct tourism.

That day, I was the only Kazakh among the Han and foreign tourists who visited Bogda Lake. The tourists were ushered to see us Kazakhs as simple people clinging onto a primitive culture. I saw Kazakh boys my younger cousins’ age renting out their horses to the Han tourists to ride on, and Kazakh women and men cooking food to serve the tourists, charging them 50-100 RMB for food and lodging. They were engaging in the “Herder Family Happiness” (牧家乐) business model that followed the “Peasant Family Happiness” (农家乐) model of rural tourism in other Chinese provinces. The lake was unrecognizable from the times I had visited the mountains we call Tengri Tau since I was a child. On the grassland where herders had once used as their mountain pastures, Chinese language songs blared from loudspeakers disguised as tree trunks in the woods, and the sound of a bell from a newly built Taoist temple echoed in the mountains. “Flying Dragon Pond” (飞龙潭) was calligraphically carved into the cliff of the lake, and pavilion-shaped tourist boats roamed in its waters. Tourist signage designated Bogda Lake as the foot bathing tub of the mythical Taoist goddess Xiwangmu (西王母的洗脚盆), rendering the Central Asian steppe landscape indistinguishable from the tourist sites in eastern Chinese provinces.

In 2005, the regional government began to relocate herders, farmers, and miners out of the Bogda Lake area; in the process, more than 1,322 households became “ecological migrants” (生态移民). In 2012, in order for the Tianshan region to meet the World Heritage application’s requirement for ecological conservation and be successfully designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site, the regional government implemented a grazing ban on 100km2 of pasture around the lake, and demolished the local shops and buildings there. After Western Regions Tourism Company (西域旅游) took over management of the lake, even the locals who used to live there must pay 215 RMB to access the lake.2 Most of the tourist sites in northern Xinjiang were inhabited by Kazakh, Mongol, Kyrgyz, and Tuvan herders in mountainous prairies with rich water resources, such as Sayram Lake, Bogda Lake, Kanas (Qanas) Lake in Altay, and the Narat and Qarajon (Ch: 喀拉峻 Kalajun) prairies in the Ili River valley. After China’s successful application for the World Heritage site title for the Tianshan region in 2013—which includes Qarajon-Qurdnin, Bogda Lake, Bayanbulak Lake, and Tömür choqqisi (Tomur Peak) in Aksu—tourism boomed.

At the “Kazakh ethnic culture garden” in Bogda Lake, an old couple who had relocated from their land told me how their lives had been disrupted by their “ecological migration” and the ensuing boom in the private tourist sector:

We have been doing tourism for quite a while. Back then we had a better location, quite close to the lake. It was quiet and beautiful; we had a lot of guests. They would stay for a night, and hike into the mountains the next day. We had a lot of traveler friends. We had livestock, and we had a tourism business. Then…we had to move here. The pastures at the top of the mountain were fenced up, and we had to sell our livestock…many people had to sell livestock. Some people left, some stayed, and kept doing tourism. But there are not as many guests as before, and they seldom stay either. We can only rely on tourism now. We used to make about 2,000 RMB a day when the business was good, and then most Kazakhs in Sangong county were displaced. Only 100 families were allowed to stay since they had worked in tourism before.

The artificially manufactured tourist landscape in Bogda Lake, which reduces Kazakhs who have lived on their land for generations to a mere commodity, is only the tip of the iceberg in the systemic dispossession of Turkic peoples and other minorities in Xinjiang. Over the past few years, global attention has focused on the gross violations of human rights such as arbitrary detentions and technological surveillance in Xinjiang. However, there remains a lack of understanding about the relations between disappearing lifeways and developmental projects that had encroached native land before the Muslim crackdown even started, let alone attention towards the plight of Kazakh pastoralists in northern Xinjiang. In this piece, I delineate a brief history of Kazakh dispossession after China entered an “ecologically-conscious” developmental stage, during which Kazakh pastoralists have not only been violently displaced for the sake of their grasslands’ “ecological restoration,” but their land and livelihood have also become exploitable resources for the development of ecotourism. The state’s crackdown on Muslims, which accelerated from 2017 onwards, has facilitated the imprisonment of Kazakh land petitioners as well as the confiscation of their land—Kazakhs have been coerced with the threat of detention to give up their traditional lands and lifeways.

Ecotourism as greenwashing and settler place-making in Xinjiang

The Chinese Communist Party’s commitment to achieve an Ecological Civilization (EC), which was written into its constitution in 2012 as a response to nationwide environmental problems, undergirds the scientific discourse of “ecological conservation” (生态保护) as a solution for grassland degradation. In pastoral regions, top-down directives have stimulated state-led conservation work that excludes Indigenous populations from being stakeholders in grassland resource management. Most of the pastoralists in China are state-designated “minority nationalities” (少数民族) that comprise only 1.3% of the national population3 but who inhabit the vast grasslands that comprise 40.9% of the country’s territory. As China entered a more “ecologically conscious” stage of development, state scientists disproportionately ascribed grassland degradation to “irresponsible” herders overgrazing their animals, instead of the environmentally destructive operations of state-owned agro- and extractive industries. After all, 70% of China’s domestic coal is exported from its settler colonies in the periphery, such as Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang, to eastern China to fuel its resource demands.4

The plight of Kazakh and other nomadic-pastoralist communities resonates with the past and present plight of Indigenous communities around the world, in that state-led enclosures of Kazakh grassland find its echoes in the green colonial land grabs that have taken place across the world. The establishment of national parks in the United States took place in the context of the dispossession and genocide of Indigenous peoples. Prior to the founding of Yosemite, members of a California state militia razed Miwok villages and murdered the Miwoks who had been obstructing the frenzy of extraction brought about by the Gold Rush; Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872 while the Plains Wars raged around its borders, and the Yellowstone Act of 1872 criminalized Shoshone and Bannock peoples’ access to the park, barring them from hunting and foraging inside.

In Panama, the Amistad International Biosphere Reserve was established in the aftermath of the US’ invasion in 1989, after which Naso, Ngobe and other forest-dwelling communities were removed from the reserve. The Panamanian government granted Texaco a million acres of drilling rights throughout the biosphere in 1990; the World Bank’s Global Environmental Facility—in tandem with the World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, and the Nature Conservancy—subsequently took charge of the biosphere’s land management program, and funded unsuccessful “alternative livelihood” microprojects and ecotourism initiatives to compensate the impacted forest-dwellers.5

In China, state directives seek to extinguish Indignenous ways of being in and relating to the land. EC’s mandate of scientific conservation and pollution reduction considers mobile pastoralism a backward enterprise that should be abandoned—herders must adapt to Chinese settler society norms and settle down, so that they can enjoy a “modern, civilized life” that provides “stable wages that enable investment in small businesses.”6 The central government set the goal in 2011 of permanently banning grazing in 100,000km2 of land in Xinjiang. In 2015, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) Party Committee issued strict environmental assessments and regulatory measures, instituting grazing bans to force the relocation of herders so that their grasslands can be rehabilitated.7

Kazakhs’ relation to their land and their mode of land stewardship—mobile pastoralism—have been invalidated according to the paternalistic, legalistic formulations of settler state sovereignty.8 Genealogical narratives entangled with land histories are important aspects of Kazakh self-identification. Kazakhs invoke the names of their homeland in turns of phrases such as ata-babamizding jeri (land of our ancestors), atameken (homeland of forefathers), and kindik qanim tamgan jer (land where my umbilical blood has shed). The names of khans, khojas (Islamic missionaries), and batirs (heroes) who fought for the people are an integral part of local histories and sometimes kept as place names. However, these historical markers are often dismissed by the state as folkloric and were even forbidden during high socialist periods like the Cultural Revolution because they were “feudalistic.”9 In order to “restore” nature to its “original”, “pristine” state (素面朝天, 还其自然), the development of Xinjiang’s native community and economy is sidelined and rendered disposable. When a mass internment system was introduced alongside it in 2016, the rhythms of removal and theft sped up, proliferating across Kazakh lands.

Coercive ecological conservation has come hand in hand with the development of rural and ecotourism to generate new sources of revenue off the land that is under “ecological rehabilitation.” In Xinjiang, conservation policies to “return” the land to “nature” take their cues from the model of de-industrialization and ecotourism (生态旅游) in Anji county, Zhejiang, whose ethos is encapsulated by the slogan “clear waters and green mountains are mountains of gold and silver.” The government and the media have extensively used this slogan in their call for the Anji county model to be adopted nationwide—a quote from Xi Jinping when he visited Anji county in 2005, when he was Zhejiang’s Party Committee Secretary, it was codified into an aphorism and even written into the constitution in 2017 as one of EC’s tenets. The state’s 12th Five-Year Plan designated Xinjiang as an up-and-coming major tourist destination,10 with southern Xinjiang to be developed into a site that would showcase the ancient “Silk Road” and its folk cultures.

As the crackdown on Turkic Muslims accelerated from 2017 onwards, more and more Uyghur villages in the south have been revamped into tourist sites by local governments in the name of poverty alleviation. Meanwhile, in the north, places from which Kazakh and other pastoralist communities were displaced are branded as places where tourists get to appreciate “nature,” recalling the way in which American national parks have been construed as a “virgin” American wilderness where settlers can worship the sublime. Many pastoralists—dispossessed by Han settlers to build bingtuan towns, or by state authorities enforcing “ecological conservation”—have had to commodify their culture, just like the Uyghurs in the south, and cater to the tourist gaze to make a living. The violence that undergirds these similar, but distinct, developments in the north and south is masked by innocuous soundbites from Chinese tourism sites that advise tourists to “see nature in northern Xinjiang and culture in southern Xinjiang” (北疆看景观,南疆看人文).

Since 2017, counterterrorism campaigns and surveillance technology have engulfed Xinjiang entirely, consolidating what Darren Byler calls “terror capitalism”,11 in which cheap unfree labor is marshalled to secure the profits for the region’s industrial complexes. Environmental conservation and tourism constitute another site where Indigenous land and bodies are capitalized.12 Tourism in settler societies like Panamanian Caribbean and Hawaii often caters to the enjoyment of privileged, affluent settlers and foreigners, and is predicated on the disenfranchisement of Indigenous peoples.13 This has been the case in the Kazakh region of Xinjiang as well. When landless Kazakhs appealed to the authorities, they were immediately construed as a threat to social stability and punished as rioters. In recent years, the crackdown on Turkic Muslim minorities created another “lucrative chaos”14 for the state to collaborate with corporate entities to appropriate grassland and imprison Kazakh activists, herders, and peasants.

By invoking the history and geographical narratives of northwestern China as a frontier to be tamed, tourism development in Xinjiang is comparable to what Indigenous scholar Teresia Teaiwa calls “militourism”,15 in which the US military played a key but clandestine role in establishing the tourist industry in places ravaged by US imperialism. Whereas the US military concealed its activities, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (新疆生产建设兵团)—or bingtuan, a paramilitary settler colonial organization in Xinjiang—is upfront about its development of Xinjiang’s tourist sector. From 2016 to 2020, it made 60 billion RMB of profit from tourism, which is double the profit made from the previous Five-Year Plan. Bingtuan’s tourism services feature ecotourism (生态旅游), cultural experiential tourism (文化体验), red tourism (红色旅游), DIY road trips and wellness vacations, and are mostly offered at the tourist sites along the Tianshan mountain range and the bingtuan towns along the China-Kazakhstan border.

In the National Tourism Bureau’s bulletin, the state stresses tourism’s necessity for the realization of the Belt and Road Initiative, as well as the political task of making Xinjiang “safe” for Han tourists.16 Tourism companies in eastern China are instructed to pair up with tourism companies in Xinjiang to assist in setting developmental priorities. One key priority is to further develop the region’s transport infrastructure to provide more convenient travel networks for tourists, such as express trains that allow tourists to directly travel from Xinjiang Aid-designated sister cities in the eastern provinces to their counterparts in Xinjiang. Under the state’s directive, the narratives propagated by bingtuan’s tourism have to champion “land reclamation culture” (屯垦文化)—Chinese settler histories claiming that today’s Xinjiang is the fruit of Han settlers’ selfless, backbreaking efforts to develop the land while defending its borders from hostile forces abroad. Reminiscent of American settler histories of frontier expansion, this myth-building process is an important normalization and disavowal of the settler colonial processes of removal and dispossession.

In many global contexts, Indigenous peoples’ land and bodies become the key sites of settler colonial violence. Across northern Xinjiang, coercive conservation legitimated by EC discourses has not only led to the enclosure of pastures and the dispossession of Kazakh pastoralists; in the cases I present in the following sections, it has also often become the premise for incarcerating resisters under the guise of maintaining social stability.

Displaced by tourism

Qarajon is one of the most beautiful and lush prairies in the Tianshan region, which is under the administration of Tekes County in Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture. The Ili prefectural government reported that it banned grazing on 2,400,000 mu (1,600 km2) of grassland to restore its ecology. While the official report notes that some counties have not fully handed out reimbursements to the affected herders, and urges local county administrators to refrain from embezzling reimbursement funds, it glosses over the herders’ on-the-ground struggles against the prefectural government. In 2011, it implemented the grazing ban without consent from the villagers, and Tekes county officials embezzled the reimbursements that were supposed to be paid to them. According to a whistleblower,17 the banned area in Qarajon (500,000mu, or 333km2) provided a livelihood for the 204 households engaged in animal husbandry. Not only did the herders not receive any state reimbursements (50 RMB/mu),18 the police also hastily drove them off their land. Consequently, a large number of livestock starved, were preyed upon by wolves, and, when chased by police cars, fell off the cliff to their death. When herders petitioned in May 2012 to be compensated by the enormous economic loss they had suffered from losing both their land and livestock, they only received 13 RMB/mu for 450,000mu of land—less than a quarter of the amount they had been promised.

Tekes County’s Party Secretary Liu Li claimed that the key to achieving UNESCO’s World Heritage designation was to ban grazing, and that the county had plans to relocate the herders and break their tradition of nomadic pastoralism in favor of rearing livestock in pens. When the prefectural government implemented the grazing ban, it only gave Qarajon herders three days to move, after which they would be driven off the land by force. In a leaked video of the Qarajon incident, Kazakh women were filmed trekking out of their land on foot, clinging onto their children and their belongings. They were indignant that the government had sent trucks to demolish their homes, saying that “their land had already been allocated to tourism sites,” and that many of their calves had died after being chased around by police vans. They complained that state cadres had pressured them to sign the relocation papers, which they refused to do because their husbands were not around. Still, they were evicted, and did not know where to go.

Later on in the video, Kazakh men in protest of their evictions tried to reason with the state police and cadres, citing the PRC’s grassland laws to argue for their legal right to access the grassland they had lived in for generations. One of them reproached the cadres,

Since this country was founded, it has been amiable and kind to us, but regarding the Qarajon issue, the government has committed a crime whose graveness is unheard of! We believe the government’s methods in handling us are wrong…the learned intellectuals of law and politics like you in those fifty vehicles that came yesterday had no right to drive people and their livestock off the land! What a crime they have committed! [The work team leaders] also tried to intimidate our entire Kabsalang village, scaring our children and wives by saying ‘your father misspoke’ and ‘your father has made a mistake.’

In Xinjiang, work team leaders, who belong to the lowest level of government, propagandize state policies and hold immense power over the Indigenous citizens they “supervise.” Based throughout the rural areas of the region, they can decide whether a citizen is “untrustworthy” and be sent to the camps for reeducation. This incident happened before the camp system was fully implemented; still, the leaders could have had them arrested as a threat to social stability. The Kazakh protester continues:

It’s been four days that we have been intimidated like this! We have done nothing but arrive at our seasonal pastures quietly. We just want to let our livestock graze and support our families. What crime have we committed? Why do you oppress us? Why are we so oppressed? Why don’t the state intellectuals who have learned the laws carefully think this through? Can the government right this wrong or not? If not, we will sue and take legal measures. We will ask for compensation for the psychological damage you inflicted on our people. Alas! Some people’s cows died, and our children were frightened…Do you know how many days people haven’t had a proper meal here? I haven’t even had a cup of water! I’ve been here day and night! (Asking everyone at the protest) Do you see anyone set up their tent? Has anyone here sat down to eat?

To quell the protest, the judicial police—led by Ili sub-branch Party Secretary Zhang Zhide, Tekes County Attorney General Mutallip, and Inspector Serikjan—was accompanied by more than a hundred police cars sent by Police Bureau Chief Wang Xinwei to arrest the resisting herders. For three days, the mountains and valleys echoed with the sound of police sirens and the panicked wails of livestock being chased down by police cars. Ili Kazakh Prefecture Animal Husbandry Bureau Party Secretary Hou Jianxin said, “it just takes arresting five or six herders to shut them all up” (逮捕五六个牧民都全都老实了).

After the herders’ forced relocation, their land was up for grabs. Through an under-the-table deal, the Ili Tekes County officials transferred the land rights of 1,280,000mu (853km2) of grassland to Haoxinzhong Tianshan (浩新中天山旅游股份有限公司), a tourism development company. The company was renamed and re-established as Kalajun Investment Company (喀拉峻投资股份有限公司) in March 201219 to manage Qarajon as an “International Ecotourism Site” (喀拉峻国际生态旅游区). Then, the company commissioned XUAR Environment Protection Technology Center to assess the Qarajon ecotourism construction project without consulting the herders most affected by the project. In 2013, Qarajon received the UNESCO World Heritage site designation; in 2016, it attained the national 5A title to cement its status as a top ecotourism site in China.20

Disappearance of land petitioners

In July 2013, two years after the Qarajon incident, a Kazakh man named Nurbaqyt Nasihat, who was a student at the Economics Department of Jiangnan University, started to write appeal letters on behalf of the herders who had lost their lands in Mori Kazakh Autonomous County (木垒) in the east of Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture. The villagers from Shoqpar Tas village (大石头乡), Bostan village, and Uzbek ranch (克木场) sought Nurbaqyt’s assistance because he was proficient in Chinese. As was the case in Qarajon, the Mori County government dispossessed the villagers from their land and embezzled large sums of reimbursements in the process. 7,000 herders in Shoqpar Tas village used to steward 7,722km2 (11,580,000mu) of land. When large tracts of grassland were privatized in the reform era, the Haptik, Dongshan, Hoshur, Kokadir, Salt Lake, and Laojunmiao pastures were enclosed, and grazing land shrank to 4,959km2. As the land use rights of these pastures were held by the Mori Grassland Supervisory Office, the Finance Bureau, the Animal Husbandry Bureau, and various branches of the county government, higher officials had to coordinate to embezzle the reimbursements meant for the herders who had to leave their land to give way for mining and road construction projects.21

On April 10, 2014, having gathered 14,000 herders’ signatures, Nurbaqyt went to petition central government authorities in Beijing with eleven other Kazakhs. In May, they were taken back to Mori with their heads in black hoods and ankles in chains, according to the testimony of Nurbaqyt’s Kazakhstan-based sister, Mariya Nasihat.22 Nurbaqyt’s family in Mori had not been aware of his whereabouts until their police friend told them of his arrest on the third day of his return to Mori. The police interrogated Nurbaqyt as to why he had gone to Beijing by beating him in hopes of securing a confession, but he insisted that he had not committed any crime. He was then detained for eight months, until the court finally opened his case and sentenced him to two years and eight months for “assembling a crowd to disrupt social order” (聚众扰乱社会秩序罪). On July 16, Nurbaqyt’s application for release on bail pending trial was rejected, as the police claimed that he was “too dangerous to be released” (取保候审后不足以防止发生社会危险性). His appeal letter, signed on July 20, asked the authorities to investigate the corrupt means by which Mori’s officials had enclosed the pastures and displaced the herders. He was confused as to why he had been sentenced for simply exercising his civil right to appeal.

The state’s intensified crackdown on Muslims in 2016 has made it convenient for local authorities to detain petitioners and protesters in Xinjiang who are otherwise not criminalized by the state’s Islamophobic policies. As Pittman Potter points out, “law and policy on economy and development in Xinjiang reflect tensions between efforts to develop agricultural, petroleum, and mineral resources on the one hand, and security programs aimed at suppressing local dissident and separatist movements on the other”.23 After 2016, laws and policies in Xinjiang consolidated a highly-securitized environment to ensure the stability and profitability of resource extraction. Nurbaqyt was released in October 2016 just as Chen Quanguo began the mass crackdown on ethno-religious minorities in Xinjiang, and had only managed to enjoy a month of freedom before the police sent him, along with the eleven Kazakh petitioners, to a detention camp to “study”.24

Internal reports from the Urumchi police department leaked by The Intercept show that petitioners are often treated as “untrustworthy” and subject to detention.25 All of the petitioners were heavily beaten in captivity, according to Mariya. Two of them were beaten so badly that they became disabled and reliant on wheelchairs. While Mariya recently received a phone call from a foreign journalist about Nurbaqyt’s release on December 24, 2018, there has been no information about his whereabouts since. The efforts by his family, who are currently living in Kazakhstan, to ask for his return have remained futile. Nurbaqyt’s Kazakhstani Permanent Residency certificate was processed in 2014, but it is not clear if he would ever be able to get out of Xinjiang.

Land confiscation under crackdown

In 2017, the Chinese government deemed Kazakhstan one of the “26 sensitive countries”—Muslim-majority countries perceived to be “harboring religious extremism”.26 Many Chinese Kazakhs in Xinjiang who used to freely travel to Kazakhstan can no longer do so, because their passports have been confiscated by the local police. Many Kazakhstan nationals are detained in camps as well, and their families in Kazakhstan dare not to travel to China and visit them. Chinese authorities view Chinese Kazakhs who have visited Kazakhstan as a threat, as they may publicize the situation in Xinjiang to the international community and undermine China-Kazakhstan relations. The state’s expanded repressive capacity provided authorities more leverage to coerce Kazakhs and Uyghurs to forfeit their land and assets with the threat of sending them to “study in the camps.”

According to the testimonies collected by the Xinjiang Victim Database,27 Chinese Kazakhs who have travelled to Kazakhstan, have family in Kazakhstan, or have Kazakhstsan citizenship or a green card, have been intimidated by Xinjiang’s local governments into giving up their land. These cases show that the processes that prevented Nurbaqyt from protesting the theft of his land have been accelerated by the internment camp system. Now it was no longer isolated incidents of large-scale theft; instead, any Kazakh citizen deemed untrustworthy appeared to be subject to land seizures and detention in the emergent internment camp system. The camp system has allowed this process to proliferate at a grassroots level.

For example, in 2017, when former farmer Erbolat Zharylqasyn travelled from Kazakhstan to Xinjiang to visit his relatives in Tacheng, the local police demanded he either return the 33mu of farmland he had been cultivating since 1997, or pay 160,000 RMB all at once. Since he refused to give up his farmland and could not pay the exorbitant amount, the authorities made him renounce his Kazakhstan citizenship. He has been stuck in Xinjiang ever since, separated from his wife and children. Esqat Bekinur had his passport confiscated by the authorities in Zhaosu county in Ili, and the village administration demanded he waive his farmland in order to get back his passport. Esqat, his older sister, and his brother-in-law have been detained in the camps since 2018, leaving his younger sister and elderly parents without financial support in Kazakhstan.

Nagima Sultanmurat, a herder in Zhaosu County in Ili, was forced to sign a document to give up her pasture of 705mu, which was valid till 2047, in order to get her passport back. However, after signing the document, the local police refused to return her passport. They would only do so once her Kazakh family members travel to Xinjiang and go through the deregistration process. When Kunim Zeinolda, a Chinese citizen with a Kazakhstan resident permit, returned to Wenquan county in Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture to resolve her pension problems, she had her documents confiscated by authorities upon arrival. She kept going to the local administration to try to get her passport back, but the authorities threatened to send her to a camp to “study” if she persisted. Later, they offered to return her passport on the condition that she abandon her family’s 30mu of farmland and give up her pension as a retired woman. She had to give up everything that she owned to reunite with her family in Kazakhstan. Many people I have talked to over the past few years face financial difficulties after fleeing to Kazakhstan from Xinjiang because they are unable to access family assets in China nor transfer them to Kazakhstan.

The widespread practices of land grabs and mass detentions associated with the camp system have also been detailed by an anonymous associate police (协警) from Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture.28 During a “100-day strike down” (百日严打) campaign in Xinjiang, even his Kazakh and Uyghur colleagues were mandated to meet a certain quota of arrests for the camps:

Around August and September in 2016, a Hui village protested the government’s seizure of their land for the construction of a police station and hospital, during which Hui houses and farmlands were demolished without the villagers’ knowledge. About 150 people gathered to protest. We arrested them and sent them directly to the detention camps—there weren’t any trials or legal procedures. They are still inside now, and I was assigned to guard the prisoners in a heavy, full-body bomb suit. To this day, this incident remains confidential. Starting in 2015, the government bought Kazakh grassland at cheap prices. In 2016, a private company bought the land for touristic purposes. We attended an opening ceremony for that private company, and we heard it was operating on land stolen from the Kazakhs.

Conclusion

As China aims to be a global leader in tackling climate change, ethnic minorities in Xinjiang and their livelihoods have borne the brunt of top-down policies that are still geared towards intensifying extractivism and economic development. Judith Shapiro and Li Yifei note that China’s version of an ecological green future is envisioned to be brought about through authoritarian governance. This is on full display in Xinjiang, whereby coercive conservation has proceeded hand in hand with tourism development, which has not only boosted national revenue but also Chinese nationalism.

In response to the international condemnation of human rights violations in Xinjiang, spokespeople for the Chinese party-state often retort by pointing out how Xinjiang’s development has stabilized the region and resulted in a booming tourism sector. Though tourism as a development strategy is endorsed by the United Nations, the World Bank, and many development NGOs as a vehicle for poverty reduction and social advancement for women and minorities, their endorsement rings hollow especially in settler colonial contexts such as Xinjiang, US-occupied Hawaii, and the Panamanian Caribbean. When the development of Xinjiang’s construction and ecotourism industries is coupled with the CCP’s political priority of maintaining stability, the government inevitably draws upon its expanded policing capabilities to dispossess Indigenous communities from their land and ensnare them in its carceral infrastructures. When the state introduces a mass internment system where all minoritized people are deemed untrustworthy, the settler colonial processes that are already in motion are amplified. Removal proliferates as a normal aspect of settler possession of a people deemed detainable primitives.

The author wishes to thank Sam H. Bass, Darren Byler, Stevan Harrell, as well as the editors at Lausan for valuable feedback for this paper. Additionally, the author thanks activist Erkin Azat and Xinjiang Victim Database for their important documentation work on the Xinjiang crisis.

Footnotes

- Anthropomorphic stone stelae on the Eurasian steppe dated from medieval times.

- Similarly, in 2013, in an effort to develop its tourist industry, the Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture government banned grazing in the 110km2 area surrounding Sayram Lake, displacing 600 households of herders and 120,000 livestock. By 2017, the off-limits area increased to 127km2. See: Salimjan, Guldana. (2021a). Naturalized Violence: Affective Politics of China’s “Ecological Civilization” in Xinjiang. Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 49(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-020-00207-8

- Pan, J. 潘家华. (2015). 中国的环境治理与生态建设 (China’s Environmental Governing and Ecological Civilization). Beijing: China Social Science Press.

- The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. (2014). China’s Coal Market: Can Beijing Tame ‘King Coal’? https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/CL-11.pdf

- Examples of green colonialism abound. In Norway, the development of wind farms within reindeer herding lands, as part of the government’s climate mitigation strategy, has endangered the life systems and ecological practices of Sami reindeer herders. See: Fjellheim, Eva Maria. Florian Carl. (2020). ‘Green’ Colonialism is Ruining Indigenous Lives in Norway. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/8/1/green-colonialism-is-ruining-indigenous-lives-in-norway

Moreover, UN’s REDD+ programme undermines local farmers’ livelihoods and way of life in Mozambique, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Brazil, Indonesia, Peru, Uganda and Kenya. See: WRM and GRAIN. (2015). “How REDD+ Projects Undermine Peasant Farming and Real Solutions to Climate Change.” https://grain.org/article/entries/5322-how-redd-projects-undermine-peasant-farming-and-real-solutions-to-climate-change - Official media often frame sedentarization as an improvement on herders’ quality of life because they do not have to seasonally migrate anymore to avoid harsh weather conditions. Moreover, the state has claimed that sedentarization comes with better education, medical care, and employment opportunities. Not only does this paternalistic narrative exaggerate the difficulties of mobile pastoralism, and neglect mobility as integral to Kazakh pastoral identity, it also construes pastoralism as incompatible with state modernity, and sees sedentarization as a way to modernize Kazakhs in order to make them feel grateful for the party-state—when, in fact, the Kazakh community in Xinjiang has long cultivated urban and rural social networks to navigate urban life and access urban resources.

- It seems that policies on grazing bans and sedentarization, which started to be implemented in 2002, have encountered numerous obstacles, and therefore have been less successful than expected, judging from the central authority’s insistence that propaganda work is important. See: National Forestry and Grassland Administration. (2020). 国家林业和草原局关于进一步加强草原禁牧休牧工作的通知, 林草发, 2020, 40号 (National Forestry and Grassland Bureau Notice: Further Work on Grazing Ban and Rest Pastoralism 2020, no. 40). http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-04/13/content_5501822.htm

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. (2021). Incommensurable Sovereignties: Indigenous Ontology Matters. Routledge Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies. Edited by Brendan Hokowhitu, Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Linda Tuhiwai-Smith, Chris Andersen and Steve Larkin. London and New York: Routledge.

Akins, Damon B. Bauer Jr. William J. (2021). We are the Land: A History of Native California. University of California Press. - Salimjan, Guldana. (2021b). Mapping Loss, Remembering Ancestors: Genealogical Narratives of Kazakhs in China. Asian Ethnicity, 22(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2020.1819772

- Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Government. (2009). 新疆维吾尔自治区国民经济和社会发展十二五规划纲 (Outline of the 12th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region). http://www.plandb.cn/plan/1032

- Byler, Darren. (2021). Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City. Duke University Press.

- In just one month alone in July 2017, the Sayram Lake tourist site had a net income of 10 million RMB (~1,5 million USD) from ticket sales. According to the 2020 Bingtuan statistical yearbook, in 2019, tourist numbers reached over 33 million people, and tourism in Xinjiang generated 20.7 billion RMB of income, more than half of the revenue generated by the service industry (56.3%).

Since 2016, in Xinjiang’s Ili and Altay regions, the number of “Herder Family Happiness” tourist services has increased by 40%, compared to the 12th Five-Year plan’s timeframe of 2011-2015. In 2019 alone, rural tourism in Xinjiang served 10.34 million tourists, resulting in 400 million RMB in tourist spending.

- Mollett, Sharlene. (2021). Land, Servitude and Embodied Histories-of-the-Present: Troubling residential tourism space-making on the Panamanian Caribbean. The Social Justice Institute Noted Scholars Series Public Lecture. University of British Columbia. Mar 24.

Hokulani K. Aikau ; Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez. (2019). Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478007203 - Cliff, Tom. (2016). Lucrative Chaos: Interethnic Conflict as a Function of the Economic “Normalization” of Southern Xinjiang. In Ethnic Conflict and Protest in Tibet and Xinjiang: Unrest in China’s West. Columbia University Press.

- Teaiwa, Teresia. (2016). Reflections on Militourism, US Imperialism, and American Studies. American Quarterly, vol. 68 no. 3, 847-853. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/aq.2016.0068.

- For incarcerated and exiled Uyghurs and Kazakhs, Han Chinese people’s ability to enjoy tourism in Xinjiang is a form of social privilege—only they have such free access and mobility.

- The Qarajon (Ch: Kalajun) riots of 2014 (Қаражон оқиғасы; 2014 喀拉峻事件; قاراجون وقيعاسى) were documented by an anonymous whistleblower, whose video on Youku, a Mainland chinese video streaming site, was subsequently censored and removed. The video is now available on Youtube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z5ALhhhmGno). This anonymously edited video contains a state media report from China Central Television, screenshots of government documents, a rare clip of herders who are just evicted from their homes, as well as scenes of protest and subsequent mass arrests in Qarajon. Subtitles that criticize the local government are juxtaposed with the official state narrative. They criticize Tekes county officials’ embezzlement of the state fund that is meant to reimburse the dispossessed herders.

- The video exposes the lies of Tekes county officials. For example, on December 3, 2011, the head of the Grassland Management Office head, Meng Gujiang, said on CCTV that he had banned pastoralism on 70,000mu of land. He also claimed that the government had publicly informed the affected herders of its reimbursements. However, the banned area was much larger and the herders were not informed of the reimbursements. The video also notes that the state media report on the positive changes in Qaradala village in Tekes county is fabricated. Herder Bahtiyar was instructed to say that his life condition has improved after sedentarization measures were implemented, that he had received the 50 RMB/mu reimbursement, and that his livestock number had increased. The livestock was actually borrowed from his neighbors for the video.

- Xinjiang Kalajun Investment Co., Ltd. 新疆喀拉峻投资股份有限公司 has a registered capital of 130 million RMB. Xinjiang Chenbao newspaper reported on the story of Chen Gengxin and Wang Guozhi coming to invest in Qarajon. Originally from Guangzhou, Chen went to graduate school in the US and returned to China to do business. In 2011, the first time he visited Qarajon with Wang, he was impressed and immediately thought of turning this place into “China’s Yosemite” (中国的黄石公园).

- The company invested 1 billion RMB to develop tourism in Qarajon.

- According to Mariya Nusihat’s testimony for Nurbaqyt, Mori county leader Kairat sold the 100-year land usage certificate to coal mine and salt mine companies. Her appeal letter, which outlines the coordinated embezzlement of reimbursements, can be viewed in Nurbaqyt Nasihat’s entry in the Xinjiang Victim Database.

- Her testimony was conducted with conducted with Serikzhan Bilash, the co-founder of Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights Group.

- Potter, Pittman B. (2013). China’s Legal System. Polity, 127.

- According to Mariya Nasihat, the twelve land petitioners are Nurbaqyt, Dalelkhan, Janat, Asai, Sayra (F), Elay, Rasul, Kurpari (F), Muwiq, Jarkingul (F), Rahat, Qumar. Except Nurbaqyt, the last names of the 11 other petitioners are unknown.

- Grauer, Yael. (2021). Revealed: Massive Chinese Police Database. The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2021/01/29/china-uyghur-muslim-surveillance-police

- The 26 countries include Algeria, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Kenya, Libya, South Sudan, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Iran, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, and Russia.

- “In numerous documented cases, the state not only detains but also confiscates (land, property, money). We now have a list of (32) entries where this is mentioned.”

- This informal interview is conducted by exiled Kazakh activist Erkin Azat, who is currently based in Paris. It is titled “I am an associate policeman: they even arrested associate police to meet the quotas.” (我是协警—他们为了充人数把协警都关进去了)