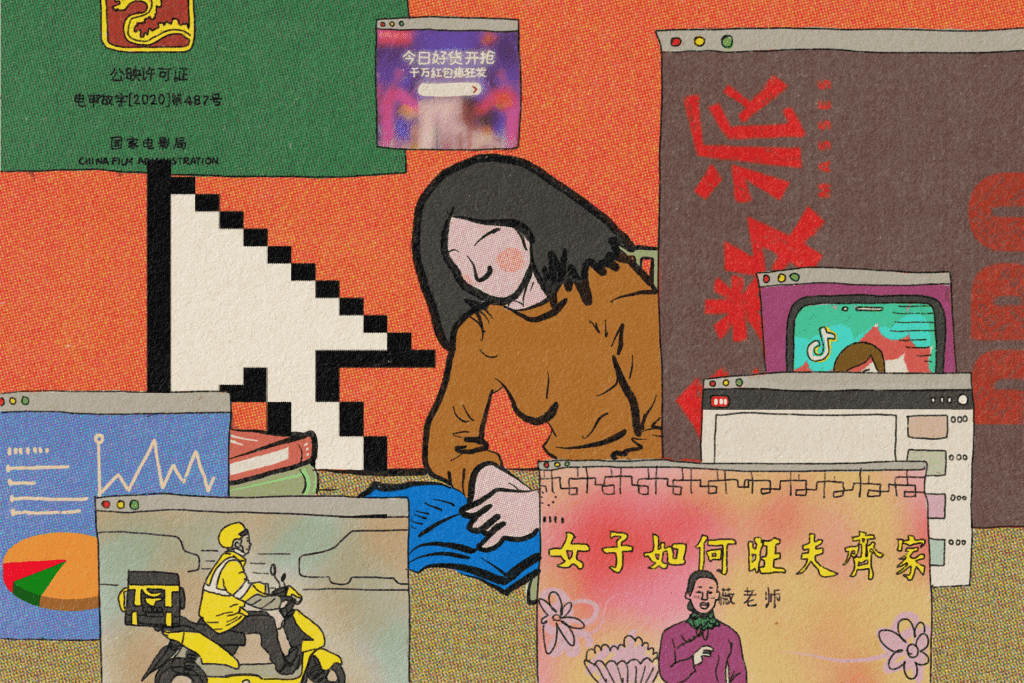

Editor’s note: This International Workers’ Day, we pulled together translations and writings from our archive to highlight the incredible breadth and diversity of grassroots worker organizing in both Hong Kong and China. As Summer’s article at the top of this list reminds us, continuing cross-border exchange against shared exploitation under capitalism is the only way forward in this new era of enhanced repression.

These 11 articles show that we will also need to continue to build collective power to fight for both labor rights and political liberation by organizing across society—not just amongst industrial workers but across campuses and in the most intimate, domestic spaces of our lives. And not only will this require cross-border exchange, but a truly international front that cuts across the “fissures of empire” by centering the needs of workers and the power of grassroots organizing, not the priorities of states.

1. It’s time to organize: Lessons learned from dissent in mainland China

With the national security laws now in effect in Hong Kong, it is time that we realize what Beijing has known for so long: that the fate of Hong Kong and mainland Chinese people are deeply connected. This is why we must not only develop solidarity across this border, but build it to last. Only then will we have a chance of withstanding state oppression in the long run.

2. What can students do for workers in China?

The current environment is sending us the message that if we want to survive, we must compromise. But that’s just what the regime wants us to think. The regime could effortlessly destroy us, but it actually prefers to keep us barely alive so that it can continue to surveil and study us in order to plumb the depths of civil society. We, in turn, become implicated in the regime, indirectly contributing to its strength.

3. Resource: ‘The Future of the New Union Movement’

The New Union Movement Research Group, part of Borderless Movement, has created a zine that walks through the basics of building power through grassroots unionization efforts in the specific socio-political conditions of labor in Hong Kong. They conclude that unions as vehicles for participatory democracy are a key element in the future of resistance against government repression.

4. Leaderless movements must build power with the rank-and-file strategy

For Hong Kong, the rank-and-file strategy does not mean a narrowing of the broad political alliance needed across many sectors of civil society to build a mass movement, but a strategic and pragmatic coalitional politics that prioritizes building power in formations that can best counter the CCP’s bureaucratic capitalist machine at its weakest points. Doing so requires a clear political understanding of how the system and mass movements work, rather than an indifference to the types of forces that compose our movement.

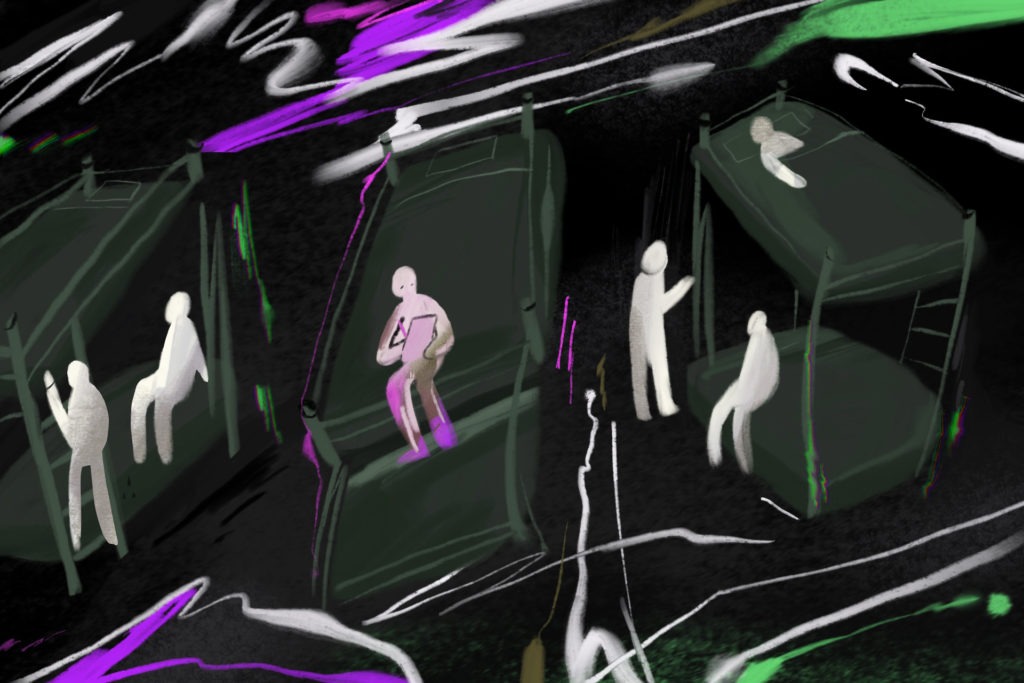

5. Factory diaries: My life as an undercover student worker

What similar struggles from two people with such differences in background, age, and personality. What is the cause of their shared misery? Their experience may be typical of migrant workers in their 20s and 30s. When can they settle down to form a family and have a promising career? Confused and lost, my coworkers often distract themselves from the grind by asking for a leave, skipping work, or quitting. This is the imprint of the era on a whole generation of migrant workers. I believe we can continue this conversation about our future and our personal goals while delving into more emotional topics, like family life.

6. From analysis to action: Voices from left media in mainland China

As engaged young thinkers, Masses 多数派 is well aware of the systemic privileges and material benefits they reap as part and parcel of the current knowledge economy of meritocracy and profit, and hope to use their limited power to stand with shared struggles across the world. Against a zeitgeist defined by structural indigence and proletarianization, Masses 多数派 is committed to an internationalist politics in class struggle; there are no “Others” in revolution, only “us.”

7. ‘We just had the heart to fight the boss’: A Hong Kong leftist’s story

Kuen’s experiences complicate a linear perspective of Hong Kong’s political opposition and its histories, and shines a light on under-reported aspects of political organizing in the city—some of which are obscure even to many of his fellow Hongkongers. Kuen knows well that there are neither easy victories nor total defeats. From organizing his co-workers as a rank-and-file truck driver to serving as a community de-escalator in the protests last year, Kuen’s story takes us from Hong Kong’s little-known workers’ organizing and left-wing circles to the frontlines of an international geopolitical struggle. Through his political biography, Kuen reminds us of what he sees as the core values of being a left-wing organizer and political activist.

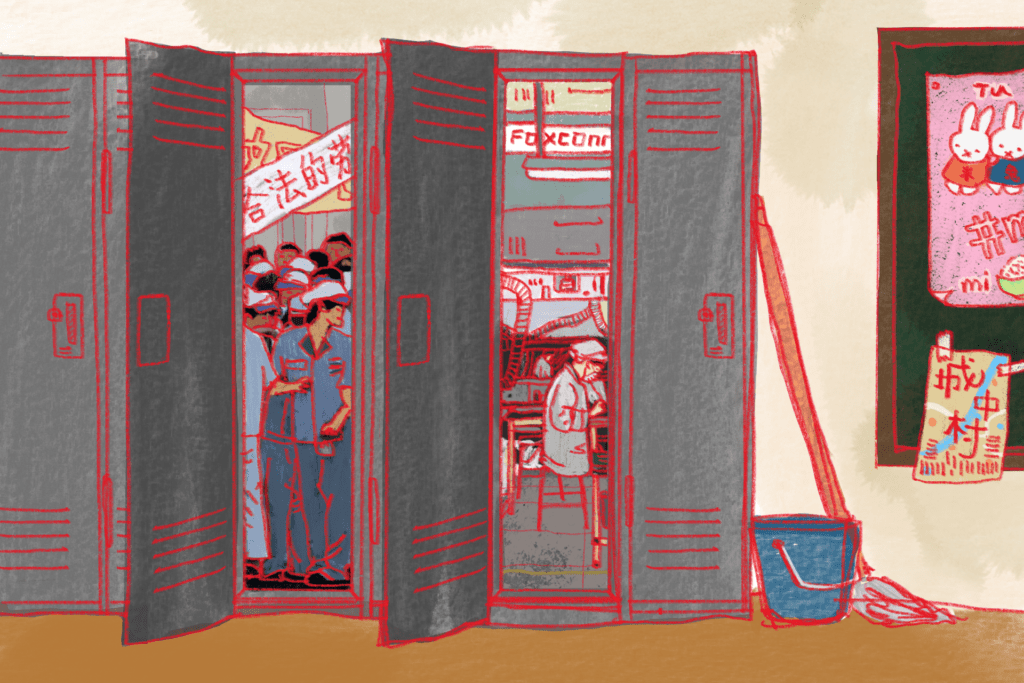

8. 15 years as a student, mother, and Foxconn worker

2020 marks ten years since the Foxconn suicides. The 18 successive suicides of young workers and the uncovering of conditions on Foxconn’s shop floors in 2010 set off a media storm of public controversy. But Foxconn, Apple, billionaire chairman Terry Guo, and consumers like us have more or less cast the deaths to the back of our minds. Foxconn’s exploitation of workers continues to profoundly alter the courses of their lives.

9. Capitalism needs you to lose your job

Since the end of 2019, new labor unions have mushroomed in support of the anti-extradition law movement. By January 3, 2020, as many as 1,578 new unions registered their founding. The labor movement that had begun to thrive alongside political protests gives us a glimmer of hope: will the ongoing struggle that began in June 2019 gain new traction through labor? Will the new wave of unions mobilize a new public dedicated to pushing for unemployment insurance and other labor rights?

10. Series: Care workers in the epidemic

What other relationships may develop between a “jeje” (MDW) and a “Ma’am” (female employer) apart from one of employment? What about male carers and the issues they have been facing? Even if the public provision of care services improves, how much autonomy do carers and carees really enjoy? Carers’ lives in the time of the coronavirus pandemic certainly reflect the complexity of the problems we have discussed so far, but what possibilities or problems come to the fore as they process, react to and resist these structures of domination?

11. Solidarity with Filipino domestic workers across the fissures of empire

The impression that many Hongkongers have of the wholly self-interested MDW actually reflects how these workers have been situated in a position of economic precarity that has only been exacerbated by how they are treated in Hong Kong. When we call for international support in our movement, have we ever paid attention to the struggles of others, or recognized Hong Kong’s positionality in these struggles, and paid our dues within the global community? Do we know what Filipino MDWs are fighting for in their struggles? What kinds of oppression do they face in both the Philippines and in Hong Kong?