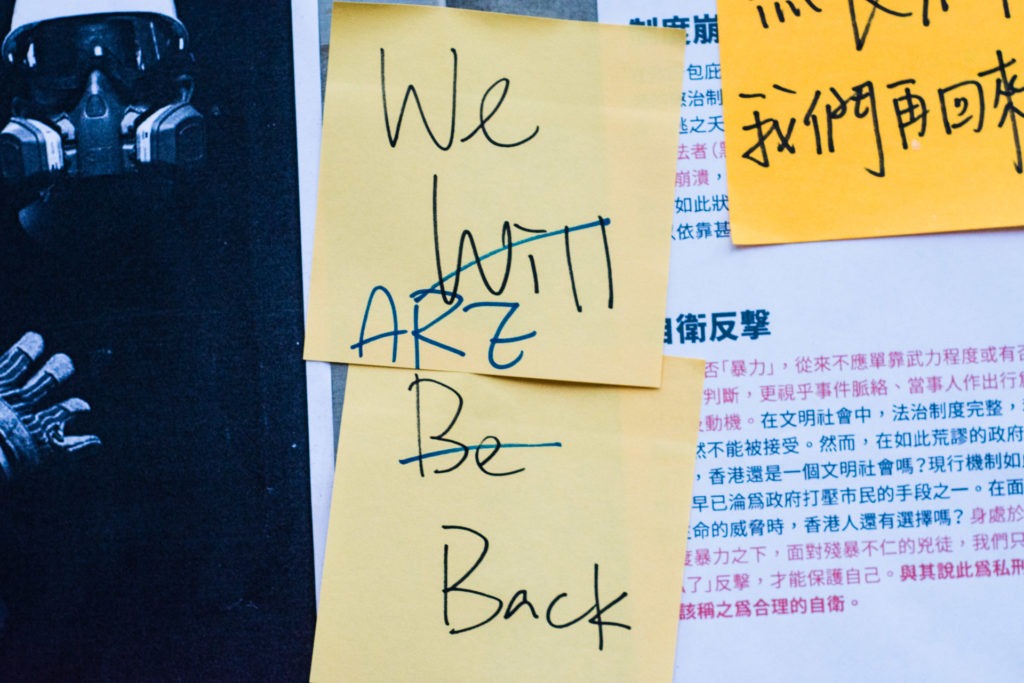

Editor’s note: In early February 2020, Hong Kong’s hospital workers came out in force to mobilize for a weeklong strike in response to the government’s mishandling of the coronavirus outbreak. Since December in the previous year, the Hong Kong movement has turned to trade unions as a means to exert political pressure and unlock a new front of resistance. Across workplaces and sectors, workers have been organizing and politicizing coworkers, bringing longstanding problems of labor rights and workplace conditions to light while forging a decisive connection between economic and political demands.

One year on, we continue to organize in solidarity with comrades in Hong Kong as they build collective power to fight for both labor rights and political liberation. Revisit our translating and writing on the many challenges of the fledgling union movement, the history of strikes in the colonial and postcolonial era, and the plight of grassroots workers.

1. How the ‘lion rock spirit’ crushed Hong Kong’s calls for strikes

Depoliticization and repression in the colonial and postcolonial eras have left the labor movement in a weakened state. Shunning collective action, many Hongkongers interact with politics without an awareness and intentionality beyond seeing strike action as purely a means to an end, a tactic with no ideology. Joining trade unions or other political organizations, however, are actions that expand the public sphere and create opportunities for like-minded people to connect—necessary prerequisites for an organized, long-term struggle.

2. Rising up against injustice: Janitorial workers in the age of disobedience

HKCTU interviews Ah Long, a long-time sanitation worker charged for “obstructing a police officer” in the anti-extradition bill protests. He enumerates the worsened conditions that janitorial workers face today—stagnant wages, exorbitant rent, the increased prevalence of outsourcing—in contrast to the easier times of the decades past, and laments his colleagues’ decision to remain apolitical in the face of 2019’s upheaval.

3. From unorganized street protests to organizing unions

The inability of front-line direct action to yield concessions from the Hong Kong government has organically led to the emergence of a trade union movement. Initially focused solely on making non-material political demands, the movement has since started to make material demands concerning workplace conditions and such. Unlike the deliberately leaderless nature of front-line protests, it has taken an institutional route that requires planning, organization, and engagement with electoral politics.

4. The dilemma of the new union movement

Although 2019’s protests were precipitated by formally political concerns, survey data suggest that economic and livelihood issues may have contributed to the upheaval. Nonetheless, economic issues have yet to be centered in the democracy movement, given the tendency to frame political concerns through the lens of identity politics. While the new union movement is well-positioned to draw connections between political and economic issues, it needs to move away from ad hoc mobilization to an emphasis on everyday resistance and organizing, and explore different ways to strengthen union membership.

5. ‘I am willing to take a bullet for you. Will you go on strike for me?’

The call to “unionize and resist” at the start of 2020 resulted in a wave of unionization. Protesters’ eagerness to experiment with different tactics may reinvigorate organized labor as a site of political struggle, an avenue that has been sidelined since the 1960s. Many new labor organizers hope that workers will see how their workplace issues have root causes in poor policy-making and resource allocation and take action against them.

6. The present is the beginning

Labor organizer Leo Tang writes to HKCTU from prison, arguing that the wave of unionization has brought about a paradigmatic shift in the wider movement. It is up to the new labor movement to unearth the potential to sustain the pro-democracy movement through the transformation of mass mobilizing relations that unionizing has achieved, so as to add substance to the wider movement’s thinking around identity, politics, and economics and bring out diverse discourses.

7. As one of the organizers of the union battlefront, I have something to say

“Is a general strike useless? You can ask the same question of other battlefronts: Is the Legislative Council useless? Are rallies and protests useless? In reality, over the past year, we have stopped trying to calculate the usefulness of a course of action before trying our best to make it happen.”

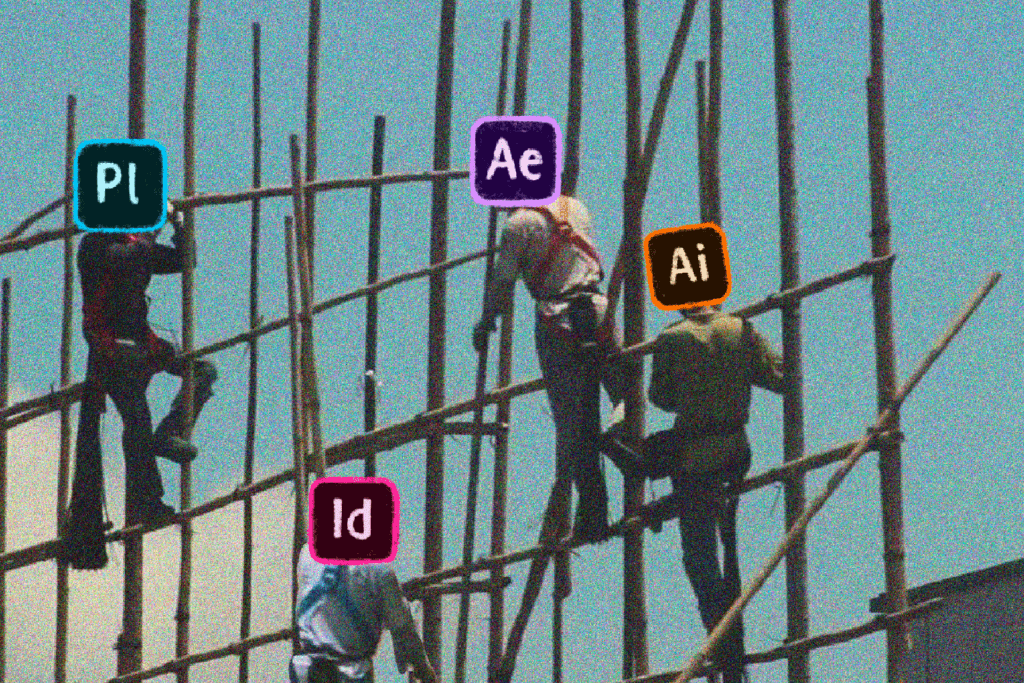

8. For Hong Kong design workers, political resistance and labor rights go hand in hand

Since the calls for the three strikes—work, school, and market—last year, the union has made a comeback in the public sphere with a focus on its usefulness in the context of anti-establishment struggle. While there had only been 11 new union registrations in November 2019, applications increased to 109 by December. In early 2020, the Labor Department received 600 new union registrations. The Hong Kong Design Individuals Union is one of them.

9. The shifting sands of an anti-authoritarian union movement

Pro-democracy organizations operating in civil society under Hong Kong’s faux-liberal system need to break out of its usual single-issue approach. Traditionally, different interest groups pursue their agenda in isolation from one another, culminating in a division of labor in civic advocacy. Instead, what we need is an “industry-focused civil society network.”

10. The ins and outs of grassroots worker organizing on the frontlines of Hong Kong’s uprising

From removing shards of glass and debris after a pro-establishment business is vandalized and cleaning up roadside garbage after protests, to bearing with unemployment and new challenges to their livelihood, blue-collar workers have become collateral damage in a movement in which they themselves participate.

What do they think about the protests as a whole, and how have they come to understand the “pro-democracy” movement? How do grassroots organizers begin to address the discrepancies between the demands of the movement and the lived experience of blue-collar workers?

11. A new labour movement birthed from the flames of struggle

When a trade union concerns itself with more than just labor rights, it represents in the resistance not only workers from its sector, but society as a whole. To maximize the political fervor that the new labor movement can generate, it must not simply struggle for improved worker rights, but also rally and bring together different groups in society.