Originally published in daikon*. Republished with permission. Read this article in Chinese.

There haven’t been any responses from my Baba-jaan’s relatives in Kashgar in our family group chat for almost two years now.

Some of their last messages were photos of themselves wearing arranged mannerisms, uncomfortable poses, and awkward smiles while embracing Chinese state officials during an imposed home stay as a part of the government’s “Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism” policies. After that, there were messages that my youngest aunt’s husband hadn’t come home from work, and that he may have been arrested. And after that, messages from my cousins trying to find the fastest way back home from their respective schools in Ürümqi, Beijing, Shanghai, Xining, Chengdu, and Chongqing. They wanted to go to her — she was then alone at home — to help her find out what was happening. There hasn’t been a word from them since.

My father’s family are Muslims of Sarikoli Pamiri descent, a people who are indigenous to Tashkurgan, otherwise known as the “Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County” in the Kashgar Prefecture in the West of Chinese Occupied Dzungarstan & Altishahr, which is itself more commonly known as the “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR)” or “East Turkestan (ET).” My uncle, my youngest aunt’s husband, is of Uyghur and Kyrgyz descent.

I’m sure many of you have seen it in the news by now — the mass incarceration of Muslims, most visibly of Uyghurs (but also impacting Sarikoli/Tashkurgani, Xik/Wakhi, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Salar, Kachee, Santa/Dongxiang, Bonan, Xibo, Yugur, Oirat, Daghuur, & Hui communities), into internment camps for “political re-education” that the Chinese government has officially labeled “Vocational Education and Training Centers” for the purpose of “counter-terrorist” indoctrination. Reports of torture, solitary confinement, sexual violence, brainwashing, penal labor…

In light of all of this, diaspora communities who call the region their Homeland have been seeking answers for lost contact with family members. We have been calling upon the world to pay attention to Islamophobic discrimination, human rights violations, ethnic cleansing, cultural genocide, and the legacies of Han-Chinese chauvinism and Sinosupremacist imperialisms. Until recently, it almost felt like the world just didn’t care. There was some concern, but not enough to generate the kind of energy from allies and accomplices in joint-struggle to throw down with us.

Every now and then, there’d be an article in a major, English-language news publication about what was happening. Sometimes it would be detailed, sometimes not; but it would never be on the front page of anything. The article would only capture the attention of those who were already concerned, informed and aware of the situation — or someone who knew someone else whose family was impacted.

On July 17, 2019, Trump met with victims of religious persecution in China, who asked him to take action. His responses were short, and led many to believe that he had no idea about any of it. This was almost a week after 22 UN ambassadors had delivered a letter to Coly Seck, the President of the Human Rights Council, and Michelle Bachelet, the High Commissioner for Human Rights, calling on them to urge the Chinese government to “uphold its national laws and international obligations and to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms” in relation to the arbitrary detention of Muslims. This was the first collective international response of its kind about the camps, in large part possible because of the activism of impacted communities in the diaspora with the support of allies and accomplices.

Nothing was done to uplift the voices of communities calling attention to ongoing state violence. Instead, our suffering was tokenized for an imperialist prerogative.

But it wasn’t after this letter that more attention was dedicated to the camps by the corporate media outlets from which most people get updates about global current events. Instead, this only happened after Trump’s meeting.

Increasingly, there were mentions of what was happening to Uyghurs and Muslim minorities in “Xinjiang” — but mostly for the purpose of contributing to a larger narrative meant to reiterate negative, sensationalist, xenophobic, psychocultural perceptions about China as an economic threat to the United States (and “the West”) in the midst of Trump’s trade war. Nothing was done to uplift the voices of communities calling attention to ongoing state violence. Instead, our suffering was tokenized for an imperialist prerogative. After Trump’s meeting, we began to see an increase in support for lobbying efforts calling for punitive sanctions against China in retaliation for the mass detention of Muslims, most visibly of Uyghurs.

Diaspora movement organizing isn’t a monolith, and there can be varying political opinions within different groups working to address the same issues. The increase in attention from journalism outlets about the ongoing persecution of Muslims in China has primarily manifested in disproportionate attention given to the lobbying efforts of ETNAM (East Turkestan Nationalist Awakening Movement), a Washington DC based group that doesn’t have the support of the majority of the global Uyghur diaspora and has a reputation for espousing right-wing aligned, anti-communist, and pan-Turkist leaning rhetoric. The effect of this attention is to flatten and conflate the work of Uyghur organizers from a multitude of movement organizations to all be a part of ETNAM. In reality, many different organizations are working towards the same goal for an end to the incarceration of our family members.

The response from various self-proclaimed left-leaning individuals on the internet with large followings has been to express denialist remarks about the existence of the camps entirely, or to outrightly defend such policies even if doing so contradicts their previous statements in support of prison abolition or against the global Islamophobia industrial complex. Rather than focus on uplifting the voices of impacted communities or developing an analysis of how various voices have been tokenized and politically manipulated in order to promote US military aggression in the name of humanitarian intervention, the denialist response has instead promoted the idea that we are unworthy of transnationalist solidarity.

Racist, anti-Chinese sentiment in ‘the West’ can exist simultaneously in a world with Chinese social, political, and economic dominance in Asia along with neo-colonial financial, industrial, and infrastructure development deals in the Global South.

This has been especially heartbreaking for me as a community organizer to the places with which I am local to. I have not seen nuanced engagement that looks beyond dichotomies, beyond the political manipulation by nation-states which keeps our movements divided, and building community bonds. Instead, people I have thrown down with have either silently pulled away from being in community with me, outrightly expressed denialism, and/or have veered into a political perspective that is uncritical of the Chinese Communist Party altogether while accusing myself and anyone with ties to Chinese Occupied Dzungarstan-Altishahr of contributing to anti-Chinese racism, anti-Asian self-hatred, or redbaiting.

Racist, anti-Chinese sentiment in “the West” can exist simultaneously in a world with Chinese social, political, and economic dominance in Asia along with neo-colonial financial, industrial, and infrastructure development deals in the Global South. Chinese & Amerikkkan Imperialism can coexist as systems of oppression. The claim that the internment camps are supposedly a “counterterrorist” policy, and the fact that this so closely parallels the US military prison located within the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, demonstrate this. The refusal, of so many I had once trusted, to engage with these complexities has left me in a state of grief about the capacity for building a united front for collective liberation.

The work of resistance and dismantling all systems of oppression is messy. If our struggle is to be based on collective solidarity, it must be resolute in naming how our histories are interlaced with violence. We cannot dispose of people whose lived experiences do not match up to our ideological assumptions and projections. We need to continue building our transnational community relationships. Relationships that are dedicated to standing in solidarity with all communities affected by state violence wherever it exists and occurs. Relationships that are bold enough to openly address that we live in a complex world with multiple geopolitical interests that are invested in keeping our movements divided. Relationships where we are all willing to be accountable for the harms that our respective privilege has imposed onto and stolen from other communities, and from that point on, imagine otherwise.

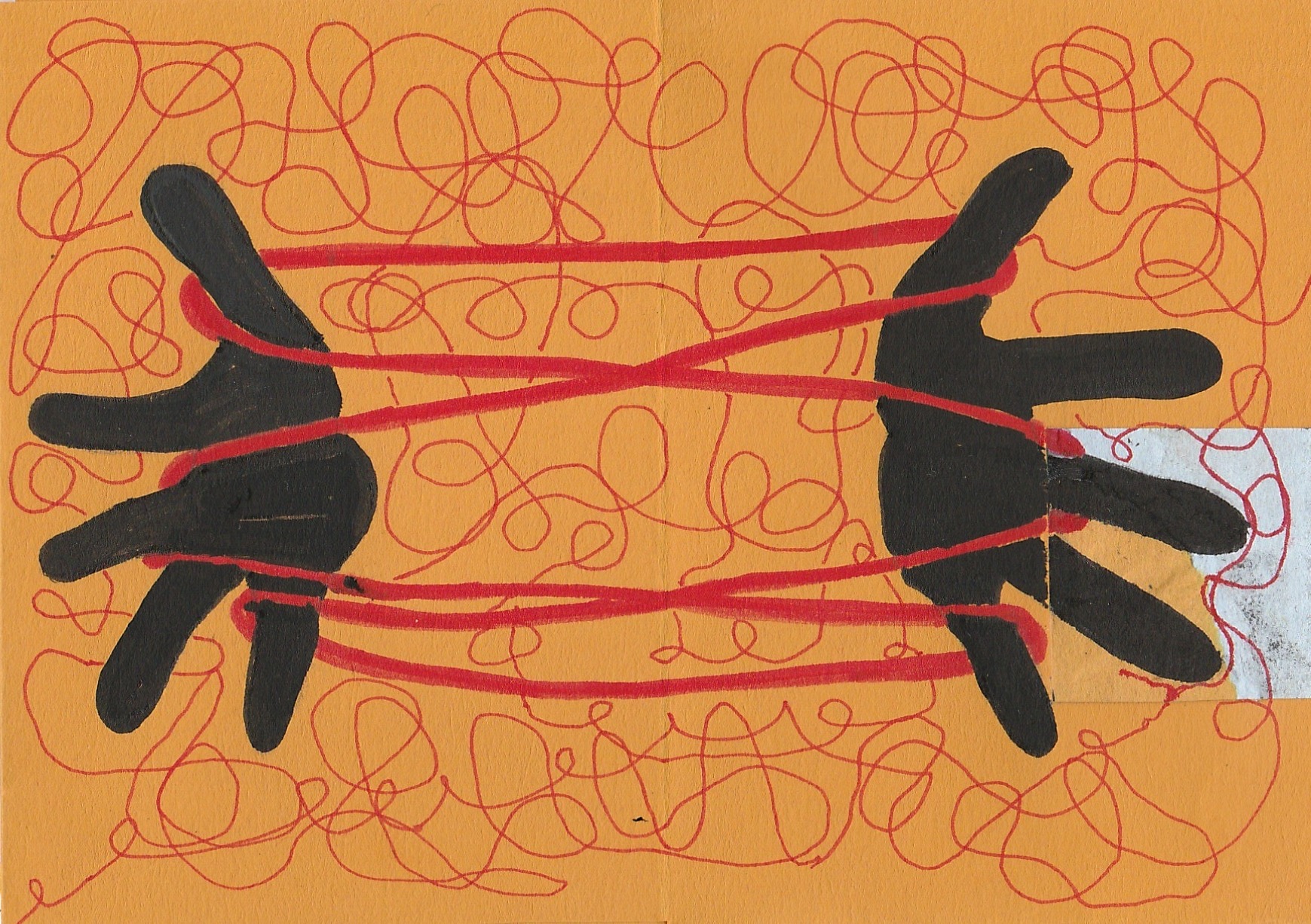

Nurdoukht Khudonazarova Taghdumbashi is an artist, linguist, patient advocate, and organizer of mixed Sarikoli, Kachee, Tajik, and Korean heritage living and working on occupied Ohlone land. With her work she seeks to interrogate diasporic fragmentation, cultural reclamation, and both inherited and persistent colonial traumas with textile design, linguistic analysis, and gastronomic memory making. (Instagram: @mandu.manta)