Read this article in Chinese.

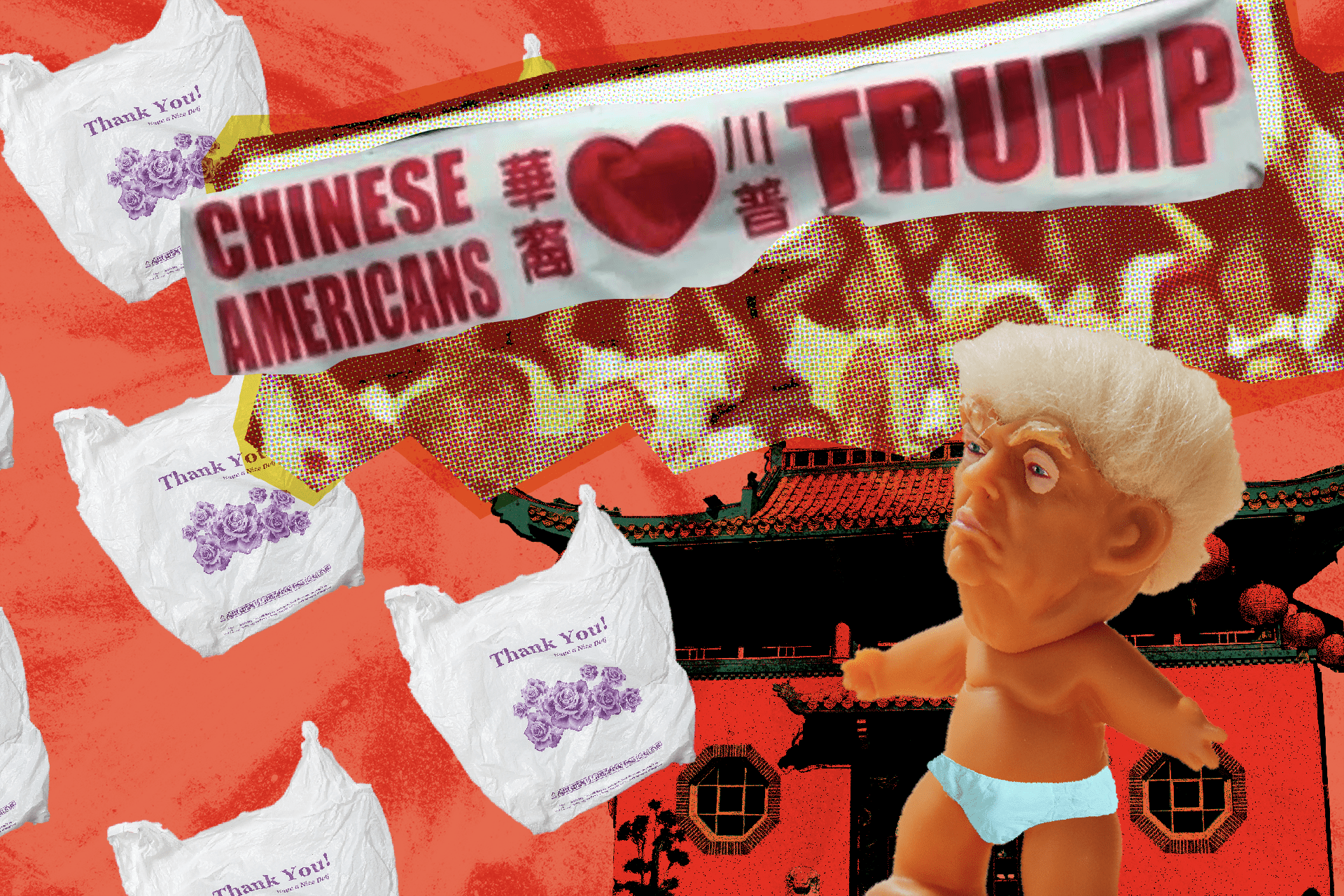

Chinese American conservatism in the US has always existed. But since their emergence in the mid-2010s, the Chinese American Right who immigrated from China have—primarily through the use of WeChat—become adept organizers and mobilized Chinese Americans to support Trump, among other conservative campaigns.

Although the Chinese American Right continue to organize against affirmative action and police reform, Trump’s scapegoating of China for the COVID-19 outbreak has increased xenophobia and anti-Asian hate, weakening the Chinese American Right’s national influence among the broader Chinese immigrant community in the US. Additionally, the 2020 Asian American Voter Survey conducted by AAPI Data shows that over 51% Chinese Americans are “very often” or “somewhat often” worried about experiencing hate crimes, harassment, and discrimination because of COVID-19. This presents an opportunity for progressive Chinese Americans to engage with and organize the Chinese immigrant community.

In this essay, we will go through the basics of understanding the new Chinese American Right, where they came from, and what new approaches and strategies we should use to engage with them today.

Who are the Chinese American Right?

The new Chinese American Right are made up of a vocal minority of primarily first-generation, highly-educated, middle-class Chinese immigrants. The majority live in suburban areas and come from a generation who migrated to the US in the 1990s.

The Chinese American Right are not Democrats or Republicans per se and vote differently depending on the issue. In fact, the majority of Chinese Americans identify as “independent voters” and have not had much contact with either party. They also have lower voting rates and are less vocal about their political views than other Asian American groups. This has resulted in progressive and liberal organizations dismissing this segment of the population, which has fueled a sense of neglect and isolation from Asian Americans—a sentiment that the new Chinese American Right have exploited in winning over the Chinese immigrant community.

The new Chinese American Right see the broader Chinese American community as their main target, and have had the greatest influence when it comes to organizing this group. They use aggressive tactics, including sensationalism, exaggeration, and even disinformation to sway Chinese immigrants to align with their political interests.

Against affirmative action

One pivotal moment that gave rise to the new Chinese American Right was in 2014 with the Senate Constitutional Amendment No. 5 (SCA-5) in California—legislation that would reinstate affirmative action in higher education.

When affirmative action was first deployed in the 1960s, people of color only had low-income job opportunities in the US, making this legislation incredibly important. It helped people of color, including Chinese Americans, gain access to more and better opportunities in their education and professional careers. At that time, most Chinese Americans were supportive of affirmative action because they were beneficiaries of it. In 1996, Proposition 209 prohibited state institutions from considering race, sex, or ethnicity, specifically in the areas of public employment, public contracting, and public education. This effectively abolished the efforts of affirmative action in California.

The new Chinese American Right see the broader Chinese American community as their main target, and have had the greatest influence when it comes to organizing this group.

In 2014, a Latinx Democratic Senator introduced the SCA-5 to restore affirmative action in public education in California. However, Republican Senator Bob Huff spread disinformation among Chinese Americans, saying that if SCA-5 passed, it would result in a lower acceptance rate for Chinese Americans in public universities. Of course, this was fundamentally inaccurate—quota based on race or ethnicity was already forbidden by law. Nonetheless, deceitful messaging swept the Chinese American community. Conservative Chinese Americans coalesced behind the opposition of affirmative action.

The Chinese American Right took advantage of this, and organized to oppose SCA-5 with extreme tactics, including sending hundreds of people to protest and participate in direct actions against senators who supported the bill, many of whom were Asian American. These efforts by the Chinese American Right ultimately succeeded—SCA-5 did not go into effect.

Pro-police and against Black lives

The controversial case of Peter Liang was also pivotal to the formation of the Chinese American Right. In the spring of 2016, the trial of Peter Liang—the New York Police Department officer who fired the bullet that killed unarmed, Black Brooklyn resident Akai Gurley—compelled tens of thousands of first-generation Chinese Americans across the country to protest Liang’s persecution, which they viewed as an example of racial scapegoating. They stated that if white police officers were not indicted for countless murders of Black Americans, then Liang should not be indicted as well. Similar to SCA-5, misinformation about the legal system spread among Chinese immigrants.

In the end, Liang was convicted of criminally negligent homicide and sentenced to perform 800 hours of community service with no jail time. However, despite Liang’s sentence, the Chinese American Right claimed that their organizing efforts were a victory. This “successful” national campaign, which mobilized thousands of Chinese Americans across the country in over 15 major cities, consolidated the Chinese American Right’s base and identity.

Against data disaggregation

The controversy around data disaggregation—which would break down data by ethnic group versus the sweepingly generic “Asian American” category—was also a watershed moment for the rise of the Chinese American Right. Chinese Americans feared that disaggregating data would hurt their children’s chances of getting into top schools.

Led by national Southeast Asian groups like SEARAC and local Southeast Asian grassroots groups, campaigns pushing for state-based legislation to disaggregate data in 2016 were successful in Minnesota and Washington. But beginning with California’s efforts that same year, opposition led by the Chinese American Right succeeded in weakening data disaggregation efforts. In 2017, Chinese American opposition to the data disaggregation bill (House Bill 3361) in Massachusetts worked, preventing the bill from passing and significantly increasing the risk of Southeast Asians and other communities of color from being underserved.

This initiative became another major issue that the Chinese American Right built their audience around.

WeChat as weapon

Throughout these campaigns, the Chinese American Right relied on WeChat to mobilize Chinese immigrants with major disinformation campaigns. Unlike Facebook and Twitter, WeChat in the US is almost exclusively used by first-generation Chinese Americans. As a result, Chinese right-wing disinformation campaigns spread viciously on WeChat; many new immigrants were unable to verify news claims because of the language barrier.

WeChat has also been used to pit Chinese Americans against other minority groups. During the Black Lives Matter movement, the Chinese right-wing promoted anti-Black racism by flooding WeChat with videos that portray Black Americans as violent criminals. In the past, they used similarly racist rhetoric to attack Muslims and Mexicans in the US.

Since there is a lack of racial diversity on WeChat, racial groups that are stigmatized are often not able to defend themselves. This allows the Chinese American Right to tap into the fears of Chinese immigrants and indoctrinate them to discriminate against Black Americans, Muslims, and LGBTQ people. Today, the majority of the content on WeChat in the US express conservative right-wing views, which plays a major role in influencing the political beliefs of Chinese American users who rely on the platform for news.

Why do they support Trump?

There is a huge generation gap when it comes to Chinese Americans’ attitude towards Trump. According to the Post-Election National Asian American Survey, about 35% of Chinese Americans were Trump supporters in 2016 but among first-generation immigrants from China, this is much higher. This number decreases sharply among second-generation Chinese Americans. Part of the reason is because many first-generation Chinese immigrants are highly susceptible to right-wing disinformation on WeChat. To make matters worse, Chinese immigrants are increasingly educated and wealthy due to cuts to family based immigration. They are often put off by liberals and progressives whose messaging treats Chinese immigrants as if they are all “poor and working-class.” As a result, many first-generation Chinese Americans tend to be conservative due to a tendency to distance themselves from progressive and liberal rhetoric.

Chinese immigrants have already had a 200-year history in the US and have had numerous experiences with discrimination in the country—such as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. When the new Chinese American Right immigrated about 30 years ago, many of the explicitly racist policies had long been alleviated, leading them to believe that these US policies were not racist towards Asian Americans. As a result, many have not felt the need to unite with other Asian Americans or people of color to fight for their rights. Instead, their strategy has been to ally with wealthy, white conservatives.

A new era of xenophobia

During the 2016 election, many right-wing Chinese Americans participated in the Chinese for Trump campaign. However, Trump clearly didn’t take Chinese Americans into consideration when he called COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” and “Kung Flu.” This has spurred violent hate crimes against Chinese Americans, alarming the Chinese American Right who remain concerned about anti-Chinese bias. This is an opportunity for right-leaning Chinese Americans to recognize the racist nature of the American right-wing.

In addition, the Trump administration has required additional verification for Chinese visa applicants on the racist premise that all Chinese are potential spies for China. Various escalations against China, including changes to the Public Charge Rule that will disproportionately block immigrants of color from obtaining lawful permanent residency in the US, as well as the order to ban WeChat in the US, puts into question the legitimacy of the emerging Chinese American Right within the broader Chinese American community, even among first-generation immigrants who are wealthy and highly educated.

However, Chinese immigrants’ own experiences of racism do not necessarily make them sympathetic to discrimination that other people of color face. Still, we should consider this as an opening to organize and win the hearts and minds of the Chinese immigrant community. Data shows us that a majority of Chinese immigrants are not fiscally conservative and are more likely than many Republicans to support higher taxation. They also believe in “big government” and providing a safety net for new immigrants. Gun control, healthcare, and the environment are cross-cutting issues that can garner support in the Chinese immigrant community, especially among young people.

New opportunities for organizing Chinese Americans

In order to advance a more progressive agenda, we need a multi-pronged strategy to marginalize the new Chinese American Right and win over more segments of the Chinese immigrant community. This work will require us to not only deepen our understanding of the growing Chinese American Right, but also to experiment and invest in new tactics and strategies. We need to engage in short-term organizing with an eye towards long-term impact.

Currently, grassroots organizing in urban areas is under-resourced, especially Asian American groups. Progressive organizations need more capacity to do year-round grassroots leadership development and political education with working-class immigrants. We can also win over the broader Chinese immigrant community in suburban areas by building new organizations, institutions, and networks to organize the community.

While it may seem like the Chinese American Right have dominated WeChat, they are not winning; they are just uncontested. Here’s what we can do moving forward:

- Create new grassroots organizations with leadership from the Chinese immigrant community and an emphasis on young immigrants.

Most legacy civil rights and grassroots organizations are not reaching the new generation of Chinese immigrants in the US, many of whom live in the suburbs or in cities where these groups have virtually no presence. As more Chinese immigrants get politically involved, it is imperative that progressive spaces be created to marginalize right-wing ideas and push Chinese immigrants to more progressives values. In doing this, organizing young immigrants is critical. Research has shown that people under 30 tend to skew progressive on a wide range of issues, so investing in them and building them up as leaders in the Chinese immigrant community will make all the difference.

- Increase progressive discourse on WeChat.

Traditional Chinese ethnic media such as radio, newspapers and TV continue to be a major source of news; however, we need to invest in mobile strategies such as WeChat. The Chinese American Right have successfully used WeChat to spread their misinformation and organize the Chinese American community, showing that there is potential for progressive organizers to do the same. While WeChat remains unbanned, progressive Chinese American organizations must urgently develop a presence on WeChat because it is becoming the primary source of information for many Chinese immigrants. To increase our market share on the platform, we need culturally competent messaging and content in order to combat a platform overwhelmed with conservative news. Already, CRW Strategies LLC and Chinese for Affirmative Action have developed a new digital hub for progressive content creation.

To some extent, we’ve seen successes: both entities played a crucial role in creating more educational Chinese-language content and massive distribution among WeChat groups to ensure ACA-5 (Proposition 16) got on the ballot in California. A new project started by progressive Chinese American college students called “The WeChat Project” has also started to challenge the conservative discourse on WeChat. The group published an open letter in response to the murder of George Floyd that went viral on the platform.

- With US escalation against China, we need to build a broad mulitracial front.

As the Chinese American Right continue to organize against affirmative action, data disaggregation, and police accountability, it is clear that Trump and his administration are increasingly viewing China (and Chinese people) as a foreign threat. Yet Sinophobia and anti-Asian racism are inseparable. Since March, the STOP AAPI Hate Reporting Center has counted over 2,600 anti-Asian hate incidents across the country. A quarter of those originated in the San Francisco Bay Area. Meanwhile, Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian American communities are being impacted by COVID-19 at a disproportionate rate. This should be an opportunity to unite the struggles of Chinese immigrants with other marginalized groups by creating more multiracial and multilingual forums of community building.

Trump’s escalation against China and the increase of anti-Asian hate have undermined the Chinese American Right’s legitimacy. Now is the time to organize the broader Chinese community around progressive values and to build lasting solidarity between them and other marginalized communities of color.

Alex T. Tom is the Executive Director of the Center For Empowered Politics, a new project that aims to train and develop new leaders of color and grow movement building infrastructure. In 2019, Alex received the Open Society Foundation Racial Justice Fellowship to develop a toolkit to counter the rise of the new Chinese American Right Wing in the US.