Since last year’s protests, zine culture in Hong Kong has become more popular: While some have made zines to spread information on street first-aid, others have attended to collective trauma and the intense emotions sparked by the protest. These independent zines allow marginalized artists and activists to bypass censorship from established institutions, and to express their ideas on their own terms.

Zines have long existed in Hong Kong, though. Elaine Lin, collection manager of the Hong Kong-based Asia Art Archive, which houses a zine library, spoke about the development of the Hong Kong zine independent from Western punk subcultures. She noted how prior to 1991, when private, non-commercial, consensual homosexual relationships between adults were still criminalized, queer people in Hong Kong made zines to communicate with one another and to build community.

Published this past November, Ourself joined this long tradition with a collection of interviews, photographs, and mixtapes that center queer voices and experiences in Hong Kong. Harmony Yuen (editor) and Joce Chau (translator and photographer) discussed their vision and process with us, specifically articulating the importance of representing diverse experiences within the queer community, and the need for more intersectional projects that situate queer identities in relation to race, ethnicity, and disability.

Ourself is currently accepting orders for a queer-themed 2021 calendar. Funds raised will be used to produce a new issue.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Sharon: Can you tell me the origin story of Ourself?

Harmony: The most straightforward reason for creating Ourself was that Hong Kong doesn’t have a lot of magazines or zines on LGBTQ+ issues. So the simplest thought we had in mind was to create a zine with a team of LGBTQ+ editors for and about the community. Joce and I are both final-year, Comparative Literature majors at Hong Kong University, and our editors are also friends at school. It’s really a grassroots initiative.

S: Zines have gained more popularity in Hong Kong lately. Why do you think this particular genre is best suited for your vision?

H: I think it gives us more leeway and freedom of expression: Say, if we did a seasonal magazine, we might have faced lots of restrictions and expenses. But for a zine, we could prepare everything from scratch. Joce did the photography and the English translation. We have another friend who’s responsible for the layout and illustrations. And we sent emails to independent bookstores and school libraries in town, all of whom were happy to carry the zine, or add it to their collection. We didn’t face any censorship at all throughout the process. And I think that’s part of the magic of making zines.

Joce: I see the zine as a very free form of publication that anyone can dabble in. And I think that’s what we want our publication to align with: something that comes from individuals in the community instead of something dictated top-down. It’s just more independent and genuine to offer voices in that way.

Two years ago some LGBTQ+ children’s books were removed from the Hong Kong public library system. We were fearful of this kind of retroactive censorship, so we wanted to make an independent endeavor, and to avoid altering any of our content in order to fit the dominant framework of what’s “appropriate.”

H: This connects to why we wanted to do a physical copy of the zine, instead of, say, running a community account on Instagram. We want queer voices to take up physical space in Hong Kong, in bookstores and libraries, not just virtual platforms where they can be erased and silenced very quickly.

S: For folks who may not have a chance to read Ourself, how would you describe the zine to them?

H: The cover of the zine is translucent, with the image of a door on it. What we want to do in this first issue is to open that door, to allow light into the closet, and for people who might be navigating their gender and sexuality. In particular, this issue focuses on LGBTQ+ youth in Hong Kong who might be very closeted, or they might not have the chance to tell their parents and families about their gender identity and sexual orientation.

The zine is a series of interviews and photographs of the LGBTQ+ community in Hong Kong, about how they navigate relationships. And by relationships, we mean not just romantic relationships, but also queer, platonic friendships. We want to be inclusive of individuals who look for casual relationships on dating apps, and those who might not feel any romantic or sexual attraction to anybody.

S: What do you want to accomplish with this publication? Put differently, what effects do you want the zine to have on your readers and on the LGBTQ+ discourse in Hong Kong?

H: I think it’s been quite a therapeutic process, not only for readers, but also for ourselves: the editorial team, the interviewees, and their friends. I remember when we interviewed one of the couples in the zine, they actually texted me one night before our interview and told me that they were arguing a lot at that time. And they wanted us to arrange a session where the two of them could just write a letter to each other. So I think it’s really interesting how the making of this zine is also therapeutic not only for the readers, but also for the interviewees. It’s an archive of their personal relationship stories.

It’s also a very liberating process to convince these interviewees to believe in the weight of their stories, that people do want to hear about them. They might think it’s very trivial, but we want to convince them that these stories are actually very important, that these personal stories are political in a heteronormative patriarchal society like Hong Kong.

J: One of the effects that we intended for the zine is building a community through a documentation of experiences that we can relate to. We can use the zine as a space for us to exchange these experiences with each other, and explore how we can amplify each other’s voices. There are LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations and communities in Hong Kong, but they are siloed from each other: Many of these organizations or these communities are very specialized in catering to specific needs and identities, and seldom come together to talk to each other about our shared struggles and differences. We hope that the zine can open up the space for these exchanges and to push for coalition and solidarity.

We want to acknowledge that there are so many of us in the queer community, and there are some of us that are marginalized within a marginalized community. For example, trans people have specific experiences and struggles that other parts of the queer community are not aware of.

S: How did you solicit and curate these different stories in the zine?

H: We spent a lot of time on arranging the stories so that they make sense both individually and side by side. We made use of social media a lot to solicit stories. I opened an anonymous account on Butterfly, the local lesbian app, to recruit interviewees, and see if anybody would be interested in jumping on board. And we also reached out to a few Instagram accounts that specialize in gender or sex education in Hong Kong to post recruitment ads for us. Some interviewees are just our own friends.

It was difficult initially to convince potential interviewees to entrust us with their stories. It was important for us to ensure that we treated them with respect, protected their privacy, and were transparent about our operation. For example, before we met in person for interviews and photographs, we asked if interviewees have any triggers or boundaries they would like us to know in advance. And even after the interview, or during the interview, if there was anything they didn’t feel comfortable talking about, or if they’d rather certain content be taken off the record, we made it a point to respect their wishes.

We opted for this level of care because, as a part of the LGBTQ+ community as well, we understood the stakes involved. People younger than 30 years old, in the demographic of people we’ve interviewed, might have a lot of concerns coming out to their families and to their friends at school.

J: We also decided to write the zine in two languages, instead of just focusing on one language, because Hong Kong is a bilingual city, and there’s actually more than just two languages here.

H: There is also a separation between Cantonese and English-speaking activists and advocacy groups in Hong Kong. Many small grassroots organizations do not have the budget to hire professional translators, so they produce materials that are either in English or in Chinese.

J: We spent a lot of time making sure that we include different kinds of identities and experiences among our interviewees because there aren’t a lot of platforms that center diverse queer voices. We looked into the nooks and crannies on social media, using hashtags in both English and Cantonese to look for these individuals who might be interested in sharing their stories with us.

We were lucky to find interviewees who agreed to do the interviews with us who don’t identify as local Hongkongers, or were ethnic minorities in Hong Kong. Even in the Hong Kong queer community, people sometimes assume that everyone in this community is of Chinese descent.

S: It is powerful that the zine attends to the intersection between queer identities and marginalized racial and ethnic identities because there isn’t a lot of robust critical discussion of that in mainstream public discourse in Hong Kong.

H: The last interview in the zine features a conversation between two queer friends, E. and B. I recall this quote from E.: “I find it a comfort that I don’t have to explain things to B. the friend, whether it’s my sexuality, gender, certain jargon that straight people won’t understand, or really just what it’s like to be a non-cishet non-local person in a foreign place. There’s an unspoken understanding between us that I find beautiful.” It says a lot about their relationship, and about people who are perceived as non-local in Hong Kong.

Mainstream Hongkongers love asking ethnic minorities in Hong Kong whether they identify as Hongkongers, or whether they have a sense of belonging to Hong Kong. I find those questions very condescending. Even in the social movement, people are like, “利君雅係香港人過香港人” (“Nabela Qoser is more of a Hongkonger than Hongkongers”).1 I mean, of course she is. Ethnic minorities don’t have to do better than the rest of us.

J: We want to be inclusive of experiences like B.’s, but also not to separate them too much from the Hong Kong queer community because there are already so many unnecessary distinctions that we draw in our communities. We think that we need to advocate for each other. For instance, I don’t understand why Hong Kong Pride and Migrants Pride need to be two separate occasions. Migrants are a part of Hong Kong, and so we want to highlight their struggles without tokenizing them. By looking for more diverse voices from the queer community, we challenge the static singular image of what the queer community in Hong Kong looks like.

S: One of the stories in the zine was from Ming, a trans woman. She mentioned trans-exclusive practices she has experienced with a local lesbian dating app. Outside of Hong Kong, there have been a lot of discussions and debates against trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs) that declare that certain “safe spaces” should be for cis-women only. How do you see Ming’s story adding to the public discourse in Hong Kong, or more broadly, to transnational discourse on trans inclusivity?

J: Our story of Ming focuses more on how the broader queer community relates to trans people, rather than how the mainstream looks at the queer community. I think in the Hong Kong context, it is actually difficult to say where the trans community stands within the broader queer community itself. To the wider public, there are many obstacles in how we represent trans people on their terms, and how trans people are invisible in the wider social context. While we adopt a more progressive understanding of the trans people in our community, certain parts of the trans community remain invisible. For example, a lot of us still see gender through a binary framework, and that excludes a lot of gender non-conforming peers. I think that there’s much to be done in terms of recognizing or procuring safe spaces for the trans community.

H: I’m really happy that Ming was a part of this project. She identifies as a trans lesbian, and some people don’t understand why a trans woman would also be into women. I remember discussing the trans-exclusive practices on lesbian dating apps with Ming as well. She found this kind of gatekeeping on lesbian dating apps a double-edged sword. There have also been occasions where predatory cis men create accounts on the app to catfish young women. To prevent that from happening and to solidify the community, Butterfly verifies users’ identity as women by asking them to submit a voice recording. This practice excludes trans women, because not every trans woman has a voice that passes as a cis-woman’s to the app administrators.

In Ming’s words: “They wanted to secure a safe space for lesbians on the one hand, but this policy also screened out some trans women. When you wanna enter a ‘pure’ group [a community for femme lesbians], you need to send photos to prove you are a ‘pure lesbian’ with long hair. Policies like this are exclusionary, but if you enter a group with people of all labels, the dynamic can really differ. It’s always about the balance between maintaining a safe space and risking the exclusion of certain communities.”

Migrants are a part of Hong Kong, and so we want to highlight their struggles without tokenizing them. By looking for more diverse voices from the queer community, we challenge the static singular image of what the queer community in Hong Kong looks like.

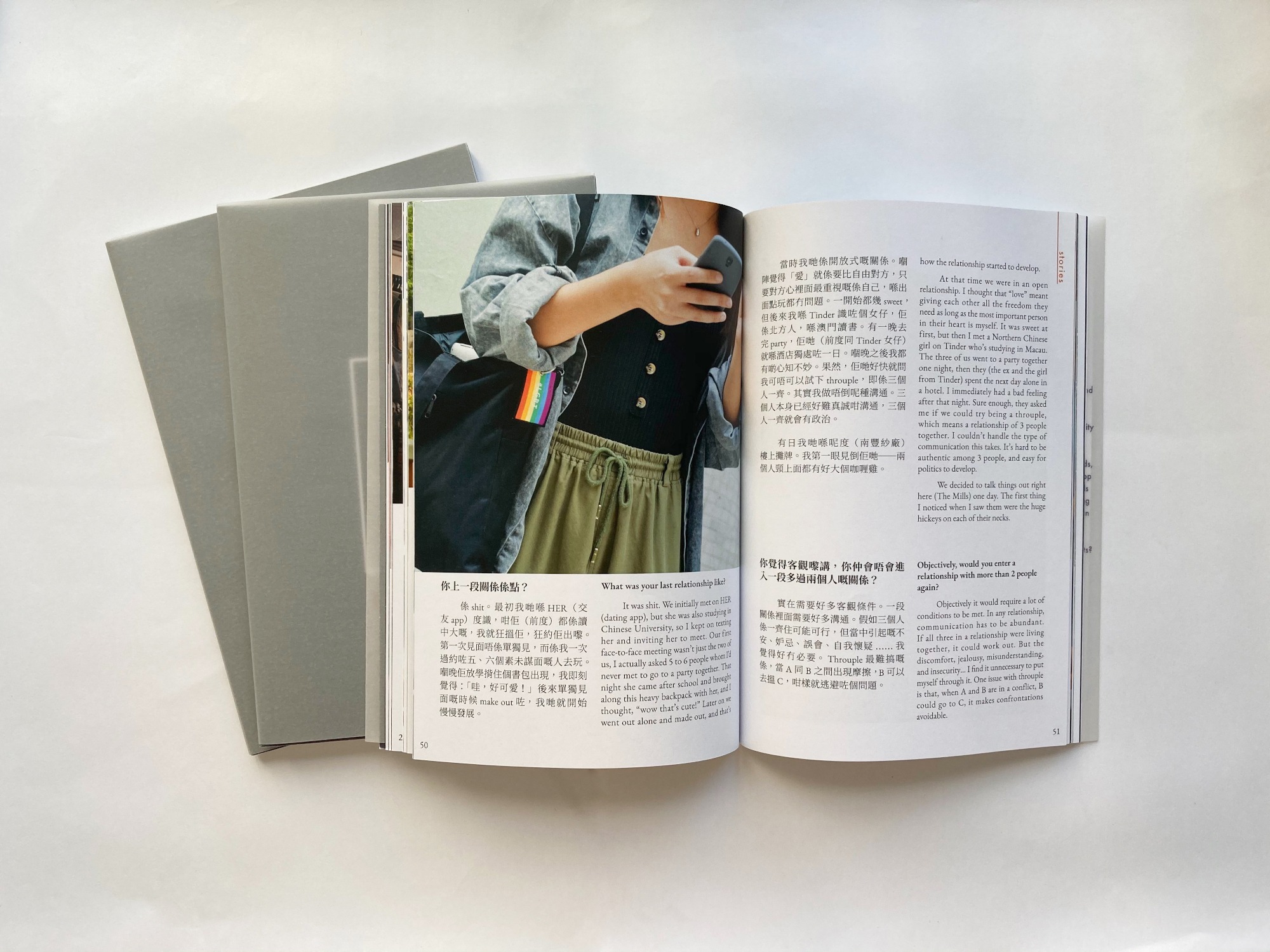

H: Joce, do you have any something to share about the photography you did for the zine, specifically how you portrayed queer people?

J: Mainstream media in Hong Kong often portray stories with queer people as sob stories. It’s almost as though if you’re queer, you must be also struggling with a lot of other things. It’s either a narrative used to generate sympathy, or is a portrayal that villainizes, hyper-sexualizes, or fetishizes queer people. I wanted to fight against these dynamics in my photographs of the interviewees.

I didn’t want the interviewees to feel like they have to perform in particular ways in order to signal that they are queer. I just wanted to capture the most genuine and authentic representation of them in public spaces because that’s something we don’t see often on mainstream TV or film.

I also want to focus on something positive about their lives and interactions. Of course the struggle of being queer in a cishet normative society is real, but I also wanted to portray how queer lives can be joyful, and they can exist in a casual and natural way just as everyone else.

S: Are there any future projects on the horizon for you?

H: Of course, we’re looking to produce new issues. But that would be at least half a year later, when we finish this semester at school and have a little bit more time to complete all the new interviews. But meanwhile, we want to continue updating our Instagram page. We’re also looking forward to more collaborations with activists and advocacy groups that specialize in advocating for LGBTQ+ youth. We had an event last Saturday to share our zine, and paired it with the Queer Reads Library showcase. I like this kind of collaboration with other grassroots organizations to keep the conversation going.

J: One of our biggest problems is fundraising, so it really depends on whether we can raise enough money to keep the project going. We really want to keep having more issues to include voices we might have overlooked in this first one.

One of our interviewees from the zine designed a queer-themed calendar for the coming year for us. We’ll invest the revenue into the next issue and keep the momentum going to highlight the queer community in Hong Kong.

S: What voices would you most want to include in the second issue?

H: We want to include more English-speaking folks in the next edition, and also feature more queer people with mental or physical disabilities, who make up a big part of the queer community.

J: We definitely want to address that intersection between disability and LGBTQ+ more in our next issue. In addition to that, we want to represent experiences that are marginalized within marginalized communities.

Footnotes

[1] Nabela Qoser is a Pakistani Hong Kong journalist. Qoser was known for her sharp questioning of government officials in Cantonese, and confrontational approach to Chief Executive Carrie Lam on the 2019 protest. ↩