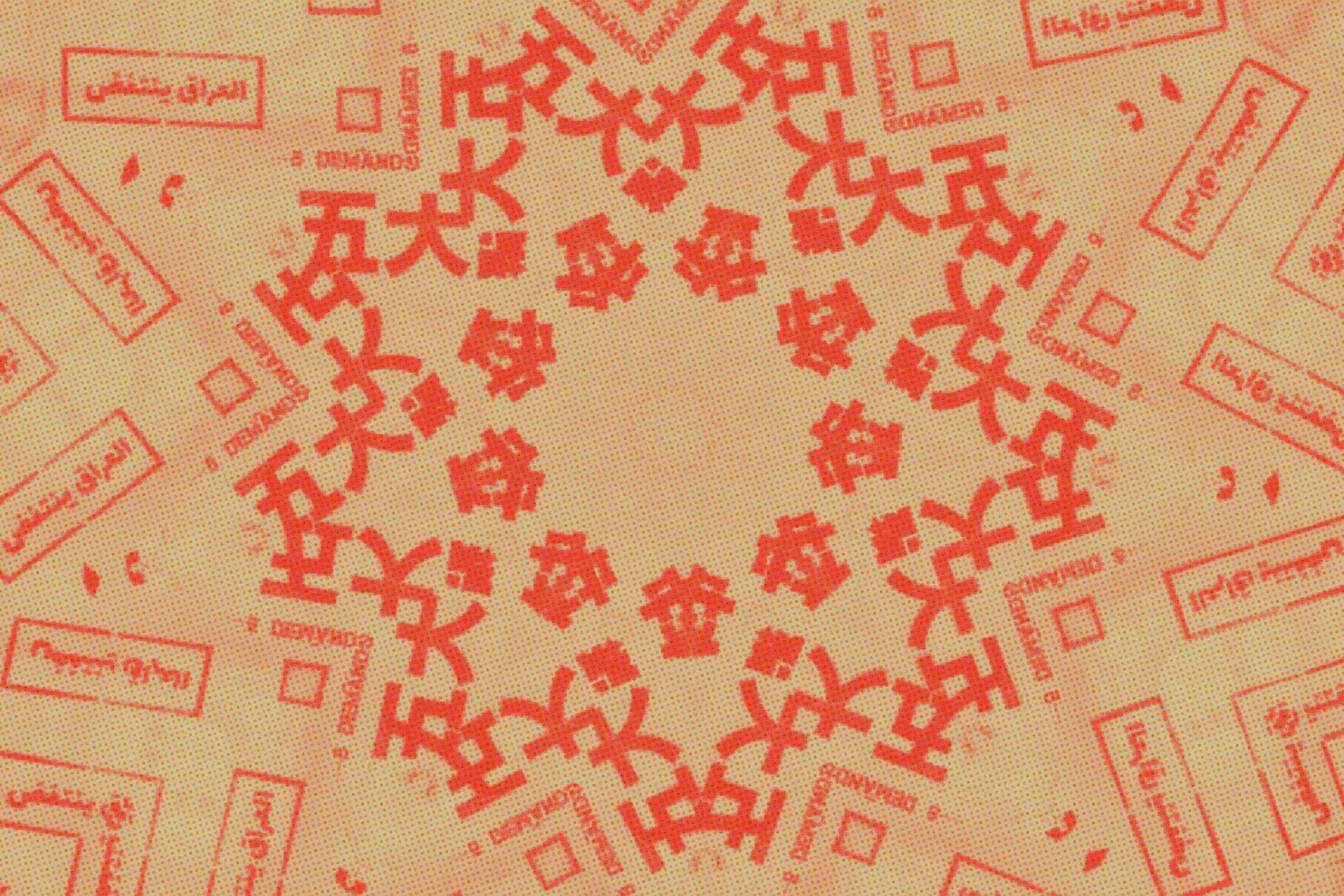

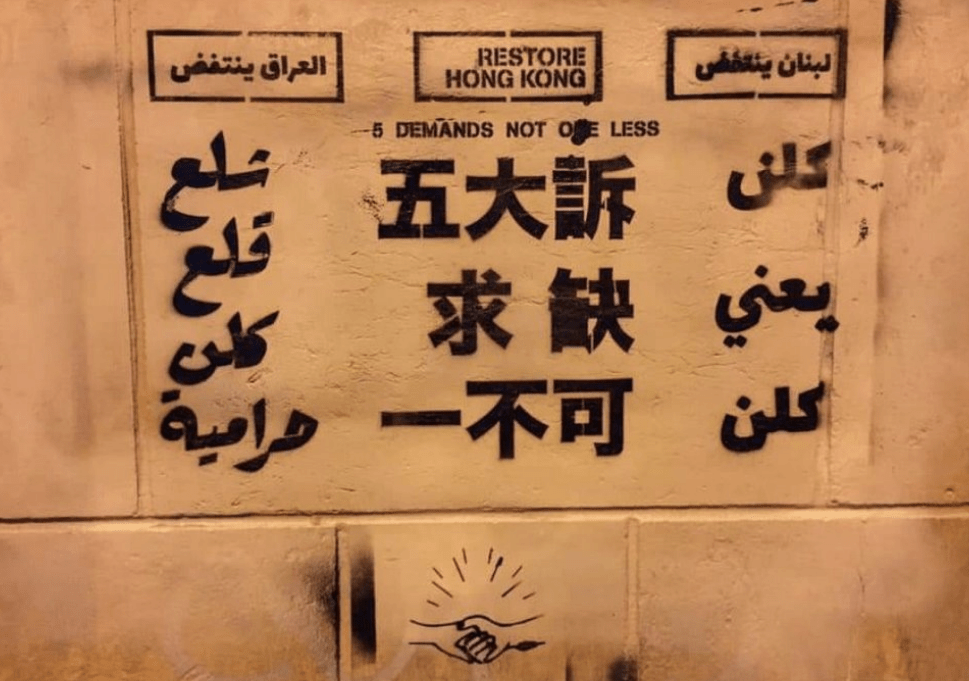

Editor’s note: In 2019, simultaneous uprisings in Hong Kong and Lebanon led activists, organizers, and writers from these two locales to engage with and think about each other’s struggles. Lausan spoke with Lebanese activist, writer, and scholar Elia J. Ayoub about the ongoing protests, the resonances between our respective sites of struggle, and the possibilities for transnational solidarity.

This interview has been edited for structure and clarity. Read this article in Chinese.

‘The people want the downfall of the regime’: Lebanon in struggle

Lausan Collective (LC): Can you tell us a bit about why the protests in Lebanon began?

Elia J. Ayoub (EJA): In Lebanon, there exists a system of sectarianism, which is essentially a power-sharing agreement between sectarian elites. The example usually given is how the president must be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of parliament a Shia Muslim. This means that, unlike in Syria or Libya or Egypt or Tunisia, or indeed in Hong Kong, Lebanon has no dominant symbol of power. There’s no Assad, Gaddafi, Mubarak/Sisi or Ben Ali, and there’s no Xi Jinping and Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

What this means is that Lebanon is both stable and fragile at the same time. It has managed to withstand sectarian strife for the most part, even though conflicts have always existed; and people have never had an obvious, individual target to try to take down. And so when Egyptians, Syrians, Libyans, Tunisians and so on were calling for the downfall of the regimes in 2011, only a minority of people in Lebanon made the same demands.

In 2015, there was a brief period of mobilization during the “You Stink” protests in 2015, which was sparked by the closure of a major landfill and the piling up of trash on the streets of Beirut and Mount Lebanon, and which was more broadly a protest against corruption in the political system.

But our moment really came in 2019, when years of widespread corruption and disastrous economic policies resulted in a severe and ongoing financial crisis, exacerbated by the nearby Syrian civil war. Finally, on October 17th, thousands of protesters gathered up the courage to chant: “The people want the downfall of the regime.” The movement remains ongoing to this day.

Between Hong Kong and Lebanon: Temporal angst and fears of ‘disappearance’

LC: What first prompted you to think of the connections between the October Uprising in Lebanon and the anti-extradition protests in Hong Kong?

EJA: Immediately after the protesters started, we began to see Hong Kong protest tactics playing out in Lebanon. Protesters began to use high-powered lasers and blinding lights to distract and confuse security forces—something they had never done before. We also learned how to neutralize tear gas based on tactics from Hong Kong.

What’s curious is that the Lebanon–Hong Kong parallels aren’t really new. Before and during the civil war (1975-1990), comparisons between Beirut and Hong Kong or Hanoi were not unheard of: it was sometimes said that Lebanon was being faced with the choice of being Hong Kong or Hanoi. For some people back then, Hong Kong, as a colonial outpost, was synonymous with capitalism and imperialism, whereas Hanoi was synonymous with socialism and anti-imperialism. Although this binary was always too simplistic, it actually created space for a segment of Lebanese and Palestinian leftists in Lebanon to link up with struggles in Vietnam.

The 2019 protests offered me an excuse to revisit some of these dynamics, deconstruct them, and find the contradictions within them. For example: Hanoi has since turned into a major player in global capitalism while the Hong Kong protesters were directly threatening and hurting capital, such as through occupations of the airport. What would the few leftists in Lebanon who were using the Hong Kong/Hanoi analogy have to say today? I suspect not much, because binaries tend to create lasting rhetorical schema that outlive their initial “purpose.” Simplistic binaries stick.

A much more interesting, in my opinion, comparison between Hong Kong and Lebanon is how “temporally fragile” they both are. While in conversation with one of Lausan’s members, your colleague introduced me to Ackbar Abbas’ book Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance and I couldn’t help but think of the word “disappearance” as being as emblematic of the Lebanese experience as it is of the Hong Kong one.

Everything we’ve ever known has either disappeared or is in the process of disappearing. We grew up with tales of Beirut’s trams and Lebanon’s trains, which were destroyed during the war. We’ve seen public spaces erased with our own eyes, our ancient forests razed to the ground, our coastline privatised beyond recognition. Our cities are still riddled with bullets. We live in a country that has some of the oldest cities in the world (Byblos, Tyre, Beirut, Sidon, Tripoli); and yet we are now trapped in cycles of violence that are at best a few decades old.

During the Civil War, it was sometimes said that Lebanon was being faced with the choice of being Hong Kong or Hanoi.

Writing in 1997, Abbas reflected on this theme in the Hong Kong context. His book prompted me to think about what the “expiry date” of 2047 means to Hongkongers. If 2047 is already here in 2020, what does that say about the blurring of the present and the future? When people feel like “it’s now or never,” how do they deal with that on the ground? How do we mobilise that fear of disappearance into a sustained movement which holds on to exactly the things which are being disappeared?1

I think a key aspect of sustaining the movement in Lebanon should come from looking to movements elsewhere, like Hong Kong’s. Unlike Hong Kong, there is no specific future date that we can associate with an expiry date. Instead, ours is a situation where the past continues to haunt the present, a reality that I’m sure activists from around the world can relate to. In our case, the “unfinished” dimension of the civil war is overwhelming. Most of the war’s warlords are still in power today, our “disappeared” are still missing, and the threat of both Israel and the Assad regime are never too far away.

A final comparison between Lebanon and Hong Kong is how migrants and refugees continue to be excluded from what are perceived as “our” protests. Migrants and refugees are largely left to simply witness the revolutions and the protests from the sidelines, as actively participating would simply be too risky. There is rarely any mention of Palestinians’ and Syrians’ struggles in the mainstream movement.

We have also yet to see a significant percentage of protesters demand the abolition of the racist Kafala (“sponsorship”) system, which dominates the lives of migrant domestic workers by tying their legal status to their employers. Binaries such as “host/refugee communities,” “Lebanese/non-Lebanese citizens” and so on are constantly being reinforced by both those in power as well as ordinary citizens. This is in contrast to the dynamics of inclusion that previously defined some periods of Lebanese history (most notably producing Lebanese-Armenians).

‘Revolution in every country’

LC: I was inspired by the chant, “revolution in every country,” that was performed by feminist activists in Lebanon, and shared widely on Twitter. Do you know how it came about? Why do you think feminists in particular wrote and performed this chant?

EJA: I think feminists are able to “see” better than other groups because they themselves live in a liminal space within the Lebanese context. They can perform a citizenship-based identity in their daily lives as a matter of survival; but their resistance against the global and domestic structures of patriarchy extends the possibility of what solidarity can and should look like. For them, the local is the global. Thus, feminists are more capable of practicing a politics that tackles intersectional forms of oppression than the rest of the population, including more traditional leftists.

In Lebanon, too many feminist activists have died in the struggle for women’s liberation. Here, I want to name Nadyn Jouny, who fought the Lebanese religious courts to keep custody of her child. Nadyn was a fellow organiser of the 2015 movement, and a truly brilliant woman and a kind soul. She died in a car accident just days before the 2019 uprising started—up till her death, she was fighting. I know that group of feminist activists was thinking of her when they chanted “revolution in every country.”

The reason this feminist chant is so important is because it forces us to get out of the loop of Lebanese history. What I mean by this is that Lebanese history is characterized by fifteen-year (or so) cycles of ups and downs. In 1943, Lebanon declared its independence; fifteen years later, the 1958 conflict erupted. In 1975, the civil war began; fifteen years later, it ended.

In 2005, the assassination of prime minister Rafik Hariri ushered in a new era of Lebanese politics, defined by the March 8 and March 14 alliances; nearly fifteen years later, the 2019 October uprisings began. More than anything, this demonstrates that Lebanese temporality is cyclical—and that whatever we do now doesn’t really matter, because the ruling class will always come out on top. We only have a few years of open window at a time before a segment of protesters end up emigrating and/or giving up.

While it is common among Arab leftists to talk about solidarity with other Arab-majority countries, the “revolution in every country” chant is not Arab-focused. I think it was a conscious decision on the part of these feminist activists to think more broadly: to list Hong Kong, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Sudan, Chile, Egypt, Yemen, Bahrain, Syria and Palestine as places simultaneously engaged in struggle.

I couldn’t help but think of the word ‘disappearance’ as being as emblematic of the Lebanese experience as it is of the Hong Kong one. Everything we’ve ever known has either disappeared or is in the process of disappearing.

Including all these other revolutions and potential revolutions in our imaginary allows us to work at different paces. It allows us, so to speak, to adopt a Hong Kong temporality and a Chile temporality and an Iraq temporality and a Black Lives Matter temporality. Today for example, the urgency of the Hong Kong and Black Lives Matter protests is palpable. Both have adopted a de facto “it’s now or never” motto. In the US, the police must be reformed or abolished (depending on who you talk to).

In Hong Kong, protesters must stand their ground and make it too costly for the CCP to continue with its plans. Prospects for victory remain uncertain in both locales. White supremacy remains embedded in the US; and the CCP is nowhere near defeated.

As a Lebanese who is seeing the protests in Lebanon “slow down” for now, the urgency of Black Lives Matter and Hong Kong is actually motivating me to keep going. The reason I’m able to continue to focus on calling for the abolition of Lebanon’s racist Kafala system is because I’m fueled by the Black Lives Matter and Hong Kong protests. The momentum for liberation is never lost; it simply picks up at different speeds in different places, at different times.

Thinking beyond cyclical temporality also enables us to understand the crucial role of so-called “failed” protest movements. I believe that every successful uprising is preceded by a series of “failed” ones; no matter what happens, we are still closer to our goals “now” for having struggled, than we were “back then.”

When people feel like it’s now or never, how are people going to deal with that on the ground?

In Lebanon, the October uprising was preceded by both national and electoral elections that mobilised unprecedented numbers of independent candidates. They “failed” to be elected; but that “failure” was only possible thanks to the failed 2015 “You Stink” movement. In turn, “You Stink” was only possible thanks to past “failed” protests by teachers, students and various groups of workers over the years. Without these failures we wouldn’t have had October 2019. And so if this movement also “fails,” what comes next might be even more impressive.

Let’s say the October uprising fails. What do we do while waiting for the next one? The answer, I think, is not wait. We have already seen what we’ve managed to do in 2019 that we didn’t in 2015. For example, we are much more tolerant or even accepting of “violence” in 2019 than in 2015. We understood that rioting and looting aren’t just some anomaly, but a very understandable—if uncomfortable—reaction to decades of injustice.

Today, we are better able to see that “normality” is itself a series of lootings: by the upper classes of the working masses. In October, we saw much greater solidarity across working and middle classes than in 2015, thus ensuring the movement’s longevity.

Exile, emigration, and new possibilities for connection

LC: More and more Hongkongers are emigrating as a result of the deteriorating political situation. How have experiences of diaspora, exile, and emigration shaped your understanding of the uprisings in Lebanon?

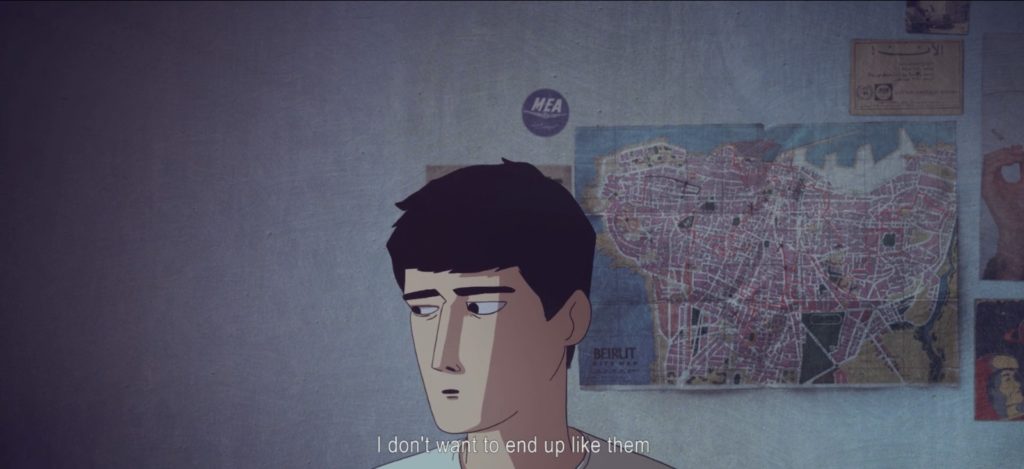

EJA: My grandfather survived the Palestinian Nakba but never spoke about it. His life was full of pain and suffering—after all, he experienced all of Lebanon’s cycles of upheaval. I have come to realize that I have carried my grandfather with me to every protest, without knowing it. By protesting, I am trying not to end up like him. That people in my generation are trying not to end up like our parents and grandparents is one of the great, untold impetuses of this uprising.

In some ways, Lebanon is a nation defined by waves of migration. From a young age, our parents tell us that we will eventually have to leave the country. We are told to seek out a second nationality alongside our diplomas. This is because no one really plans for tomorrow—we grow up in a constant state of existential crisis, or what some academics have termed a state of “anticipation of violence.”

For that reason, I was born in France (my parents left at the end of the war) and have Argentine citizenship (my great-grandfather fled the Ottomans to the Americas), even though I grew up in Lebanon (my mother came back to Lebanon after the war), went to Francophone and Anglophone Lebanese schools and universities and speak Lebanese Arabic.

To bring it back to an earlier point, people from Lebanon should be invested and committed to “revolution in every country” simply because many of us live in or hold passports from these countries. Whether we recognise it or not, we are deeply affected by world events. I suspect it’s not that different for Hongkongers.

Hegemonic narratives and false anti-imperialism

LC: Hong Kong protesters are sometimes accused by people on the left of being paid by foreign forces to destabilize the regime. Are there similar dynamics at work in Lebanon?

EJA: The sectarian power-sharing agreement means that people have to appeal to their sectarian representatives in order to make their voices heard.2 Beyond the hegemonic narratives that exist within sectarian communities, there is also the question of so-called “foreign influence.” To understand this, you have to understand the broader context of the Israel-Palestine conflict as well as the Syrian and Israeli occupations of Lebanon.

Today, Hezbollah is arguably the dominant party in Lebanese politics and a de-facto kingmaker due to its military power. It has engaged in highly reactionary politics in Lebanon, and continues to support the Assad regime in Syria. At the same time, Hezbollah is revered by “anti-imperialist” authoritarians on the Western left because of its military successes against Israel.

The momentum for liberation is never lost; it simply picks up at different speeds in different places, at different times.

As a result of this dedication to rhetorical anti-imperialism, Hezbollah and its supporters have been particularly obsessed with smearing protesters in Lebanon as being funded by foreign, pro-US (or Saudi). Online, these “anti-imperialists” are often the same people who accuse Hongkongers of being funded by anti-China forces.3

Ultimately, these so-called “anti-imperialists” share two things in common: they oppose the US government, and they want easy answers to complicated questions. The fact that there are actual Arabs or Iranians or Chinese willing to confirm their preconceived notions shields them from accusations of racism—what we can mockingly describe as the “I have a [enter nationality/ethnicity] friend” model of anti-imperialism.

At the same time, these people are fundamentally unwilling to listen to articulations of alternative political futures from people engaged in struggle in those countries. This is the irony of it all. Their version of anti-imperialism is dependent on an imperial logic.

In our case, it didn’t take long for anti-government protesters in Lebanon to point out the irony of a party entirely dependent and loyal to Iran accusing Lebanese protesters of “foreign loyalties.” Our response to these accusations—also made by Hezbollah/allies-aligned TV stations—has mainly been to ridicule them. We’ve distributed sandwiches with labels saying “Funded by the US government” and made videos with random protesters declaring “I am funding the revolution.”

‘A continuation of the revolution’: Aspirations for the future

LC: What excites you about the the ongoing uprisings in Lebanon?

EJA: There are two main things: the feminist movement and the movement to abolish the Kafala system. These two do not fit in any traditionally left-wing or anti-sectarian politics because even the dominant anti-sectarian groups tend to be dominated by men and are always dominated by Lebanese citizens, excluding the significant percentage of non-Lebanese residents of Lebanon. They also do not fit neatly into electoral or mainstream street politics, and that is precisely why these struggles can make us reimagine what Lebanon could be.

I’m interested in these movements because I genuinely believe that the most effective long-lasting political changes are those that do not neatly fit pre-existing narratives. The vast majority of Lebanese historiography pretty much assumes that Lebanese history is synonymous with Lebanese men, which means that Lebanese women and non-Lebanese men and women are essentially invisibilized. Bringing these two struggles to the forefront of Lebanese politics would be, in my view, one of the most effective ways of tackling the intersection of patriarchy and sectarianism.

That people in my generation are trying not to end up like our parents and grandparents is one of the great, untold impetuses of this uprising.

LC: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

EJA: I started protesting in my teens, fifteen years ago. In the meantime, the vast majority of my friends have left Lebanon. Protesters know we might be doing this for decades to come, which is an exhausting thought. What I have learned is that we must take care of ourselves and our own mental health to avoid burnout. At the same time, we need to also be mindful of translating our experiences for future generations, and for people across contexts. Today, protesters everywhere must also be translators, from one language to another, from one experience to another.

Between Hong Kong and Lebanon, there are so many seemingly random coincidences. But fundamentally, we are both ground under the feet of global systems of power and capital. The key to the future will be keeping conversations like these going, towards a collective liberation.

Footnotes

- People in Hong Kong and Lebanon share a kind of temporal angst, distributed across the generations. For the generations of Hong Kong people born on or after the 1997 handover, their future is increasingly uncertain. As for Lebanon, we usually differentiate between the war generations: our parents and grandparents, who grew up or were already adults during the civil war; the postwar generations, who grew up in the 1990s; and Generation Z, who grew up during the waves of assassinations since 2005. My friends and I grew up in a country supposedly at peace but which saw dozens of assassinations, a major war (2006, between Israel and Hezbollah), a major conflict (2008, when Hezbollah invaded parts of Beirut and Mount Lebanon) and the impacts of the 2011 uprisings, especially the Syrian revolution, on the Lebanese political scene. In each generation, there is a similar sense of existential angst: of not knowing what is coming next.

- The sectarian power-sharing agreement has effects on people’s lived realities. For example, as someone who is vocally anti-Assad, I am safer in Christian/Sunni/Druze-majority areas rather than Shi’a-majority areas in Lebanon. This has nothing to do with Shias, Christians, Sunnis or Druze. Instead, it is because Hezbollah, the main Shia party in the Lebanese sectarian system, is both heavily armed and invested in the Assad regime’s survival. As their presence in “their” areas is hegemonic, I have to take certain precautions when visiting friends in certain places.

- The same “anti-imperialists” who accuse people in Lebanon of being foreign-funded, as the same people who accuse anti-Assad Syrians of being Muslim extremists. Ironically, this is only possible because of Hezbollah’s (and Assad’s) instrumentalization of the post-9/11 “war on terror” logic, which labels all ideological enemies as terrorists.