Last month, Singapore’s sudden spike in COVID-19 cases made consistent headlines in international and regional news. Next to Hong Kong and Taiwan who have reported zero cases for several days now, Singapore’s uptick has come across internationally as somewhat of a surprise. But the infections have not evenly affected Singapore’s population. Migrant workers, housed in purpose-built factory dormitories on the outskirts of the city, account for 85% of the then 15,000 reported cases.

According to Minister Lawrence Wong, a member of Singapore’s parliament, the small country is dealing with “two separate infections—there is one happening in the foreign worker dormitories, where the numbers are rising sharply, and there is another one in the general population where the numbers are more stable for now.”

Because the outbreak has disproportionately affected poor migrant workers, some Chinese Singaporeans have viciously lashed out to blame them.

This split has not only been a hit to the country’s attempt at “racial harmony,” but has revealed a deeper racial fault line among Singaporean citizens. Because the outbreak has disproportionately affected poor migrant workers, some Chinese Singaporeans have viciously lashed out to blame them.

A recent Mandarin forum letter in Lianhe Zaobao, Singapore’s Chinese daily, openly blamed migrant workers for having poor hygiene, claiming that the high infection rates in migrant worker dormitories are largely the fault of residents who hail from “backward places” and bring “uncivilized” habits with them wherever they go.

Unfortunately, this bigotry is not an uncommon view among Chinese Singaporeans. In Singapore, the latest news coverage shows that both numerically and in spirit, the almost one million work permit holders, who form the backbone of reproductive labor in this gleaming city-state, are actually treated as outsiders. So it’s no surprise that the high infection rate among migrant workers ignited a new wave of anti-immigrant and xenophobic sentiments.

Singapore runs on migrant labor

That Singapore’s outbreak has hit migrant workers the hardest is no accident. It has nothing to do with hygiene standards, but rather the systemic exploitation of migrant labor in Singapore. As one discerning response to the racist forum letter said, “The dilemma that our migrant workers are facing today is a result of structural class disempowerment that sprung from a global capitalist order.”

Indeed, for the past few decades, Singapore has worked as a production factory in the game of global capital. The back-breaking labor necessary to prop up its advancement as one of Asia’s leading global cities has largely fallen upon migrant workers. But instead of getting proper health and living facilities from the government, private corporations are put in charge of workers’ accommodation.

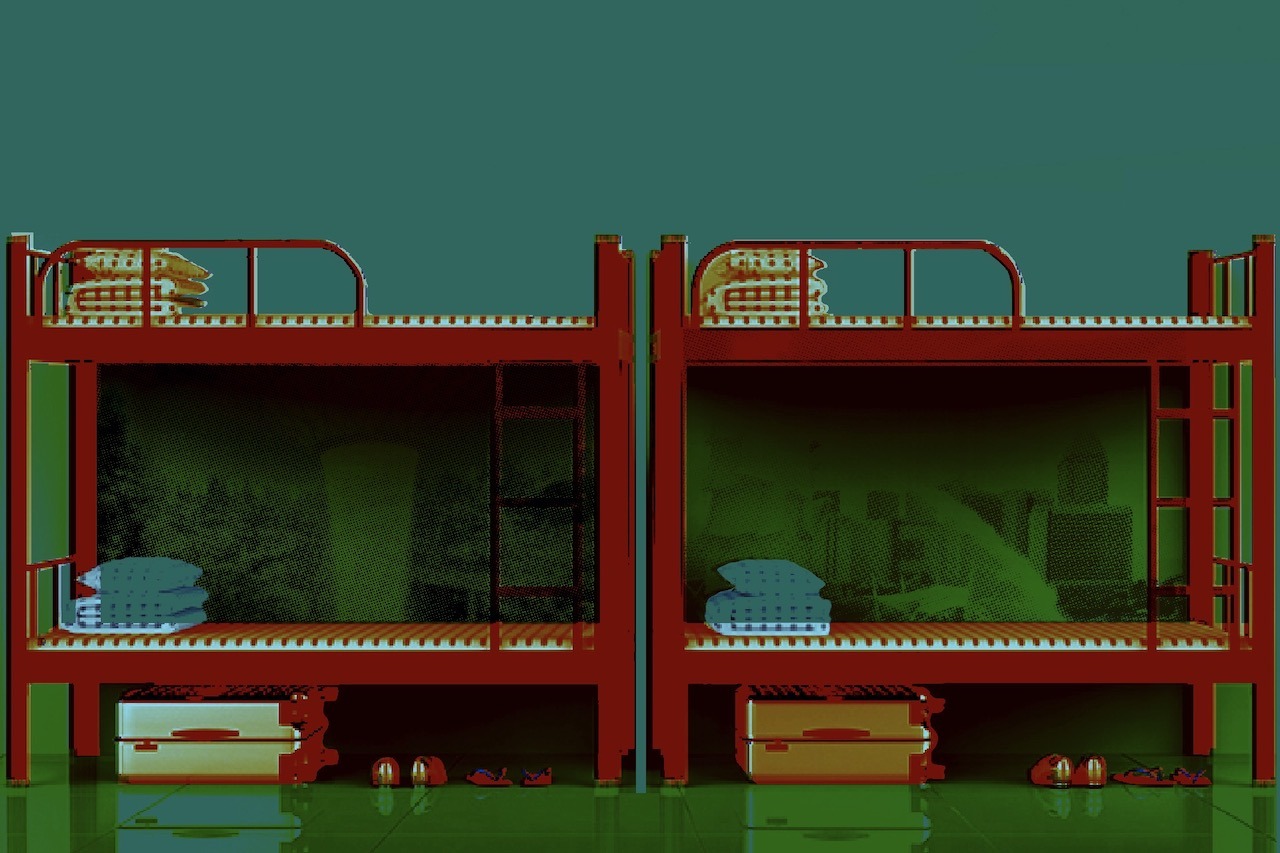

In cases where rooms house 12 to 20 men, any notion of social distancing is laughable.

As a result, these private for-profit dormitory operators tend to shove as many men as possible into a room in a bid to cut costs. In cases where rooms house 12 to 20 men, any notion of social distancing is laughable. When the whole corridor of 170 or so workers share common facilities like bathrooms and kitchens, hygiene and sanitation are beyond the residents’ control, as would be the case for anyone who finds themselves living in these conditions.

Given these circumstances, some Chinese Singaporeans’ racialization of hygiene is extremely hypocritical. While Chinese people have already been scapegoated in this pandemic, the dirty state of many public toilets in Singapore’s Chinese-dominated shopping malls rarely provokes the same disdain.

Local writers have suggested that the Singapore government should nationalize purpose-built dormitories and place it under state control. As the recent social distancing policies and penalties to offenders have shown, the government does not lack the enforcement capacity to implement orders in an organized and systematic manner.

Up till now, local businesses have only been told to adhere to new public health and safety standards for migrant dormitories. Yet, for the sake of profit, the state is turning a blind eye: the monitoring process remains lax as these for-profit companies are still critical drivers of the economy.

To be fair, while the state has not come down in an authoritarian manner to enforce a rule-and-penalty system, there are a good number of local employers who are adhering to public health guidelines and providing workers with safe living environments. But these protections that ensure the well-being of workers will never be uniformly guaranteed as long as employers remain for-profits entities.

From colonial rule to Chinese supremacy

Singapore has always relied on the exploitation of darker-skinned people. The official narrative in history textbooks notes that Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, a British statesmen and official for the British East India Company, founded the city-state in 1819. Stamford Raffles had envisioned the island of Singapore as an entrepôt for British merchants, a protective base for its opium trade with China, and an outlay for the extension of British trade in the region.

Less explained is how Singapore’s British-led industrialization resulted in decades of misery for the migrant workers on Singapore’s peripheries. British businesses saw the Chinese in Singapore as indispensable middlemen in their ambitions for intra-regional Archipelago trade. (Singapore’s subsequent prosperity as an “Asian Tiger” state had more to do with its regional enterprise and its role as an international trade hub than with industrial Britain per se.) With their unique relationship to the British elites, the class of Chinese businessmen in Singapore, who handled commercial exchanges in tandem with the British status quo, became crucial matchmakers between British traders and cheap manpower. Their local knowledge and proximity to colonial power meant that these Chinese businessmen were the perfect liaison between their white rulers and the region’s darker-skinned inhabitants. This is how Chinese supremacy in a multiracial Singapore was propounded.

Migrant workers remain extremely compliant because employers can revoke their work permits which would result in their deportation.

At the heart of Singapore’s effort to modernize was a sophisticated immigration apparatus that distinguished between types of foreign workers. While Western expatriates and the Chinese workers mostly had professional occupations, migrants from less privileged Southeast Asian countries were imported to toil as construction workers and domestic workers. However, despite uprooting their lives to move to Singapore, many have remained minimally-paid work permit holders and have been treated as second-class citizens; their precarious work contracts only last for two years unless renewed, and they are forbidden from marrying citizens or permanent residents, let alone reproduce in the country.

Today, these migrant workers still play indispensable roles in building the city-state’s twinkling skyline and state-of-the-art facilities. With salaries well under SGD$1,800—barely enough to survive given Singapore’s incredibly high cost of living—they can be seen toiling away on roadsides and on new public infrastructure construction sites. Many others are employed at factories that process food and manufacture biochemicals, among other types of blue-collar work.

Migrant workers’ rights to food security have also been under attack: their meager wages leave them with no choice but to resort to catered food that is deficient in nutrition and sometimes downright rancid. This is even worse for Muslim migrant workers who, according to HOME Singapore (Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics), have to fast during Ramadan. But despite horrid working and living conditions, migrant workers remain extremely compliant because employers can revoke their work permits which would result in their deportation.

The ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) has legitimized this division between highly educated citizens and migrant laborers as essential for the interest of the Singaporean community. The creation of a nation-wide underclass is justified on the basis of Singapore’s economic prosperity. Migrants, without access to institutional education, are often seen by local professionals as chattel to be governed rather than human beings with needs and rights.

Racism in Singapore is nothing new. It is inherited from our country’s subjugation under British colonial rule and its collusion with local capitalist elites. As the COVID-19 crisis exacerbates these anti-immigrant sentiments, let us not forget that many Chinese in Singapore were forcibly relocated from China as coolies for British trade—that we, too, are immigrants on Singapore’s land.

The government has a habit of touting the ideal that Singapore is a “racially harmonious” city, yet racism itself is foundational to its decades of spectacular profit. If we want to achieve any kind of racial justice, we must demand that the racially privileged in Singapore not respond to the unfolding health crisis with Chinese supremacy, but with a spirit of solidarity that prioritizes the economic and social well-being of South Asian migrant communities. Only then can we begin to challenge the state’s claim to a “racially harmonious” coexistence.