Original: 【疫情時刻的自組織:民眾如何重塑社會(二)】, published in Matters

Translators: 99 semi-literate Chinese diaspora under a trenchcoat, K. Cheang

This is Part 2 of a three-part series. Revisit Part 1 here. This translation has been edited for clarity and structure. Some of the original links are no longer available. If you would like to be involved in our translation work, please get in touch here.

Editor’s note: The process of translating this series from Chinese into English has involved, as with all of Lausan’s translation efforts, dialogic discussions on the most appropriate terminology to describe social phenomena across different contexts. One of the key terms in this series of articles is “自組織,” which we have translated as “mutual aid,” but may also be translated literally as “self-organization.” Mutual aid, as a concept developed by anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin, has traditionally referred to reciprocal forms of cooperation that benefit everyone involved rather than charitable, one-way giving only in times of great need. While mutual aid as a term is now entering the mainstream, it is important to reassert that it is meant to be a durable social relation that runs counter to the individualism of capitalist charity. Taking Dean Spade’s definition of mutual aid as “collective coordination to meet each other’s needs, usually from an awareness that the systems we have in place are not going to meet them” (Mutual Aid, 2020: 7), we believe that the term “mutual aid” is appropriate to describe the organizing efforts and activities described in these articles. While recognizing that experiences of, and thus terminologies for, different social phenomena cannot necessarily be translated word-for-word across contexts, we believe that the work of translation includes analyzing the resonances between forms of political practice and communicating those in a way that is legible and productive toward mutual understanding. We are invested in putting different sites of political solidarity in conversation, and thus have chosen to translate the term “自組織” as mutual aid, in order to facilitate a conversation between Chinese organizers and those engaged in mutual aid efforts around the world in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its exacerbation of existing material inequalities and oppressive conditions.

Within the current discourse, we have seen many critiques of statism and state bureaucracy. These critiques of course each have their merits, but they are also rooted in different tendencies and perspectives that inevitably affect how we evaluate mutual aid and grassroots organizing initiatives. A deeper analysis will help us understand why such a range of perspectives exist as we reimagine the role of mutual aid in our future society.

Is civil society the cure-all?

We cannot neglect the voices of those who have called for a more robust “civil society.” But can we equate this with our support of mutual aid projects? What does civil society really mean? For one, public social media account “News Lab” envisions a society where the government would practice “good governance” and individuals would have a strong sense of civic responsibility. Out of this sense of obligation, individuals would not simply follow orders handed down by the authorities, but rather have the initiative to sacrifice a certain degree of personal interests for the public good under the pandemic. At the same time, however, we must ensure that the government practices good governance: it should make decisions based on the public’s interests; it should be held to clear systems of accountability; it should adhere to a transparent decision-making process backed up by the free press and the right to free speech; it should respect and consult with experts and medical professionals; and finally, grassroots neighborhood organizations and charities should cooperate with the government. From this perspective, civil society comprises not only individual citizens whose private rights are protected and who fulfill their civic obligations, but also the political state whose powers are variously curtailed, freedoms in the public cultural sphere, professional divisions of labor across society, as well as public-interest organizations.

Chen Chun, for another, argues that the emergence of mutual aid groups during the pandemic merely signals a momentary return to civil society movements of a bygone era, and advises against an overly optimistic approach to civil society. Yet, Chen falls short of challenging the notion of civil society itself so much as take its existence for granted. The article depicts civil society as “mass society,” a mid-level intermediary form of organization. According to William Kornhauser, mass society serves four main functions: first, it takes up the tasks that the state or the family cannot handle; secondly, it can organize its members to engage in discussion internally as well as create a platform for dialogue between the state and the masses; thirdly, it facilitates the diversification of public interests and forms of identification and belonging; finally, the people can negotiate and interface with national elites through their counterparts in mid-level organizations. However, this iteration of civil society also renders the divergence between the so-called elite and the masses extremely visible. Under this model of civil society, the key to change no longer depends on the people’s ability to take initiative, but whether mid-level elites ostensibly outside the state bureaucracy choose to share their power.

This tendency to minimize if not deride the masses is clear in a range of articles that valorize an exaggerated sense of liberal individualism. For example, public social media account “Journal of Quantum Mechanics” (量子學派刊) advocates the following: “The general public lacks the requisite critical thinking skills to discern fact from fiction. Many opinions enjoy widespread approval even if they don’t hold up to scrutiny! The herd mentality is never invested in truth and reason, but instead operates on blind obedience, cruelty, paranoia, fanaticism, and two-dimensional affect. Faced with two conflicting views, even though they may contradict each other, people more often than not continue to vest belief in both.” It is precisely this kind of internal inconsistency that many liberals are frequently afflicted with. On one hand, according to the liberal design of civil society, citizens as individuals are given formal and equal opportunity to participate in public life, and are expected to act on their own initiative. On the other hand, liberals tend to be content with the fact that not every citizen is able to exercise these rights and fulfil civic obligations to the same degree, leading them to believe that the masses need to be managed by elites who can act on their behalf.

In addition, according to Chen Chun’s survey of the history of civil society movements in China, civil society is not only a static mode of social organization. Rather, it also serves as an active, agentic framework for the fight for civil rights, the transformation of the status quo, and the struggle against the state. Jing Li, in a similar vein, offers a counter-narrative to civil society as a fixed constant: “The basic logic and organization of civil society are different from those of political and economic society―the state, the party, corporations, and the market. The former fosters heterogeneity while the latter prioritizes political efficacy and economic efficiency. These three social modalities are not tied in a zero-sum nor a confrontational relation, but instead permeate, supplement, and restrain one another. For Li, anti-civil rights theory that endorses separatism and confrontation to the nation-state arose from the US’ neoliberal turn in the post-80s era, the political momentum of which accompanied the reemergence of the Republican platform in the face of the Soviet Union’s disintegration and tectonic shifts in the Eastern European political landscape. Li maintains that institutionalization and resource distribution are not the fortes of civil society, but are instead weaknesses that cede power to those who would defend the necessity of the state.

Putting aside their different views on the relationship between civil society and the state, Li and Chen’s analyses ultimately belong in the same theoretical framework that relies on a “trialectic” model based on theses three pillars: civil society, the political state, and the economic state. Chen seems to have purged the market from the discussion altogether, severing the economic terrain from the concept of civil society and creating a dichotomous illusion that seems to suggest the market is expressly absent in the formation of civil society, if not an infallible given that does not need to be subjected to scrutiny. The problem here is that it seems as if the only goal of civil society in its struggle against the state is to promote liberal democratic reforms, thus significantly narrowing the meaning of civil society as a whole. In Li’s framework, the three pillars seem to have a stable, cooperative relationship with effective checks and balances, but this is a presumption that overlooks the disproportionate power relations in between. The very ideal of the trialectical relationship in both Chen and Li’s proposals, and the interpretation of such a relationship as non-confrontational, is questionable. It is ultimately a limited theoretical construction.

In the short run, to completely eradicate the political state from human society would seem unrealistic. Nevertheless, countless regimes have been toppled by myriad instances of confrontation and resistance. There have been moments in history when the three pillars have undergone dramatic power struggles and settled in a state of chronic “imbalance”―from extreme forms of authoritarian repression toward civil society to state socialist disallowance of a market altogether. Indeed, the beginning of the pandemic witnessed a short period of “anarchist” upheaval. All in all, the presumed stability of a trialectical relationship between civil society, the political state, and the economic state cannot account for these developments.

Let us revisit Marx and Gramsci to examine the differences between theories of civil society, then and now. What Marx calls civil society is in fact an extension of the Hegelian view, which mainly refers to the field of economic activity in which private individuals engage in the production and exchange of goods by their own initiative. This domain is shaped by two key elements: market mechanisms and private property. Unlike Hegel, however, Marx refutes the universality of the nation-state, and believes civil society shapes the state, which merely expresses the former’s particularities and attendant class relations. Here, not only is the economic dimension of civil society made explicit, class struggle is also positioned as the force behind the supplanting of the feudal state by a new order as well as the impetus for social progress. Later, though Gramsci would refine the concept of civil society and extricate it from under the sole purview of economics toward the sphere of daily life, culture, and ideology, it is nevertheless clear that he considered civil society to be a new realm of struggle against the bourgeoisie.

By contrast, the sort of civil society we see being ushered in today is increasingly depoliticized if not stripped of its political economic connotations. In China, liberal intellectuals who push for political reform through the consolidation of civil society often willfully ignore political and economic perspectives that could sharpen their analysis. Just as some intellectuals emerging from the New Left seek to eliminate “zero-sum confrontations” through the rhetoric of the “third sector”―we will discuss this problem in the final section of this essay―they are generally reticent when it comes to the reality of the authoritarian state apparatus.

The exclusion of ‘civil society’ from public discourse

When civil society as a form of organization and movement becomes repressed, its public culture reflexively retreats into self-contained ideological and cultural spheres, for instance into ivory towers insulated from the masses. Consequently, the voices of the masses remain largely unheard in public debate concerning the pandemic; this amounts to civil society’s silent exile, for which the state and the market are responsible as co-conspirators―here we once again return to Marx. The crisis throws into relief the unsurprising condition that civil society has been excluded from the realm of public opinion in three major areas: the distribution of essential supplies in high demand like face masks, the shortcomings and necessary overhaul of the current healthcare system, and the conflict between corporate interests and labor rights. Without exception, civil society is squeezed out from participation and debate at every turn.

Since late January 2020, restricted quotas of mask purchases have become the new normal. Want to buy a face mask? You’ll need to scan a QR code, fill out your residency information and present your ID card. This model was first rolled out in Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Xiamen―first and second-tier cities―with only one reason: the price war on face masks.

The battlefield also spread to include media disputes between proponents of market self-regulation and those of state regulation. Global Times editor-in-chief, Hu Xijin, posted on Weibo that the government should shut down all black market operations peddling face masks at exorbitant prices and severely punish bad actors seeking to profit off of a national emergency, who would otherwise tarnish the national morale and ethos of collectivity. This exhortation has elicited an even more inflammatory response from online celebrity economist Xue Zhaofeng: “We should sing the praises of the pandemic profiteers!” For Xue, supply and demand is the name of the game. When high demand meets low inventories, sky high prices and price inflation are the logical outcome as the invisible hand works its usual magic. If prices were to drop, no one would rush to produce face masks―so goes Xue’s logic. As such, Xue believes that “those who are profiting from the crisis ultimately stimulate supply and reduce the price of face masks by reconciling the tensions and discrepancies between supply and demand.”

In the wake of the controversy, more moderate voices came to the fore. For example, the Beijing newspaper, Book Review Weekly, introduced the perspective of French economist Jean Tirole, a successor to Keynesian macroeconomic theory. Tirole believes that although queues, lotteries and executive rationing are indeed more equitable solutions than market dynamics, in reality those methods cannot be implemented effectively. In the end, there is an inevitable return to the market. But the market is by no means perfect. “When the market can no longer address scarcity in an equitable manner, excessive speculation may occur. The government should regulate the market by establishing price fluctuation ranges on the basis of information gathered from producers and traders. It should assess and address conditions in a pragmatic way, rather than enforcing simple punishments.”

In a Peng Pai News article, East China Normal University economics professor Dong Zhiqiang pointed out that the problem of market fundamentalism is that it assumes all human behavior takes place within the domain of the market, and that all social relations can be reduced to market transactions. If that were the case, all problems would “already be resolved by the price mechanism. The problem is that much of human behavior does not take place within the market domain. The price mechanism doesn’t work on social relations.” Though Dong provides a trenchant critique, we have not found anyone who takes the argument further―no theory that describes the ways social relations can develop and resource redistribution unfold outside the realms of the market and the state, even though this is precisely what many mutual aid groups are doing during the pandemic.

Another area of debate concerns institutional reforms to China’s public health system. On this topic, the social media account “Elephant Magazine” published two articles: “Why is there so much pressure for admission to Chinese hospitals?” and “What does the prevention and control of infectious diseases look like in China?” The articles argue that “nationwide measures of strong social control are gradually losing their effectiveness; meanwhile, the market has not fully become integrated as a tool of modern social management.” This is a fundamental reason why the medical system has become extremely strained under the pandemic. Since the implementation of new medical reforms, China has not only failed to successfully establish a tiered referral system in which local clinics refer patients to higher tier hospitals for specialized care, but is also seeing problems with shrinking numbers of primary care clinics and low quality standards in other facilities. What prevents good doctors from staying in their communities is “systemic oligarchy and rigid hierarchies within the medical system.” Therefore, the reform of the medical system should “allow doctors to open private practices, allow the development of non-governmental medical institutions, keep pace with developments in the medical services industry, improve the supervision of the medical and health industries, establish a system that aligns with the market economy, and support medical and health personnel by properly compensating them for their services.”

By contrast, the social media account “Contemporary Reflections” argued in response that marketization will not be able to solve the problems caused by the inefficient hierarchization of the medical system. “Within a marketized system, different standards of medical care may not be the intended effect, but is the inevitable result. Following the tradition of western economics, such a system of social relations is founded on one’s relative economic power, and one’s economic power determines one’s position in society. Provisions for care do not depend on the severity or complexity of one’s medical condition, but rather on one’s ability to pay, such that the price of medical care becomes a filtering mechanism for patients. Naturally, ordinary people within this system will not go to a large hospital with comprehensive coverage unless they have an advanced disease.” Although this article provides an incisive critique, it does not provide a very compelling solution: it simply argues that the existing system must be maintained and improved. Unlike classical Weberian bureaucracies, China has a “unique contracting-out system” which, in the author’s view, means that “in addition to the division of labor between upper and lower levels of government, there exists an important system for assigning political responsibility,” under the “political rhetoric” of “serving the people at all times.” But this conclusion is extremely naive: the author has completely ignored the fact that throughout this pandemic, bureaucrats across the board have behaved disgracefully by dodging responsibility and scapegoating one another.

The so-called struggle between the state and the market does not change the fact that they are in fact two sides of the same coin.

Actually, since 2009, the state has been continuously reforming public medical institutions and reducing the available number of public hospital beds. According to the National Health Commission’s report in the “2018 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of the Healthcare Industry,” the number of beds in public hospitals have decreased by 676 over the past two years, while the number of beds in private hospitals have increased by 2,218. Additionally, the number of public hospitals has decreased year by year. The majority of those which have not already been converted into all-purpose medical service centers have since been privatized. The path to adopting this neoliberal economic model in China―that of outsourcing public services―has not been an easy one. Data from Medical World shows that as of 2019, there are 322 private hospitals in Hubei Province, of which 18 rank in the top tier―the highest number in the country. Fosun International and Alibaba Group have also entered the medical industry one after the other and acquired private hospitals. Rather than arguing that the state and the market are at odds with each other when it comes to institutional reforms, it is perhaps more accurate to say that this very dichotomy is ideologically constructed. The so-called struggle between the two actors does not change the fact that they are in fact two sides of the same coin.

The problem becomes even clearer when we focus on the discourse around the protection of labor rights. Should we rejoice at the state-issued order requiring companies to delay people’s return to work? To do so would overlook the role of mounting discontent, as well as the efforts of mutual aid groups, which were what actually forced the government’s hand. We would also be ignoring the incentives for individual businesses to reduce pandemic-related losses by delaying the return to work, as well as the state’s failure to adopt adequate oversight measures in relation to workers’ rights. Crucially, we would be ignoring workers’ lack of effective means for scrutinizing and challenging their managers, not to mention their lack of avenues for participation. This is all a product of a longstanding lack of organized labor efforts.

In reality, we have witnessed many cases where businesses have defied the law by demanding workers resume work early; Jianjiao ran an article about the barring of student workers from entering their dorms after refusing to sign an agreement to start work again in Shenzhen. Where workers lack the experience and tools to defend their rights, state orders are revealed to be shockingly flexible in effect, as shown in the Labor Department’s sporadic implementation of labor laws.

Under these conditions, employers’ gripes about special regulations during the epidemic prevention period have been akin to tantrums thrown by a spoiled child. The social media account “Entrepreneur” criticized the Human Resources and Social Security Bureaus of Beijing and Shanghai for putting small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in a difficult situation. It implemented a policy guaranteeing the right of one worker per family to stay at home to care for under-age children, while receiving normal pay. The policy also guaranteed the right to double time pay (the weekend rate) for all employees who work overtime before the official return to work date: “In these circumstances, being ordered to pay double time or an extra person’s wages could bankrupt a business.” The authors conclude with a rhetorical question, “With the skin gone, what’s left for the hair to stick to?” Intentionally or not, this critique revealed the quintessence of the current paradigm: the skin-hair analogy does not only apply to the employer-worker relationship, but accurately describes the market economy-state apparatus relationship.

Against the same backdrop, the state of labor rights continues to deteriorate. When we praise service workers such as delivery riders, taxis drivers, and couriers for sustaining the “pulse of Wuhan,” we ignore how the gig economy model adopted within the capitalist system brutally exploits these workers. On 4 February, while most cities were still delaying the return to work, Meituan, a company that has monopolized the take-out/delivery industry, required all riders to go online or face the deletion of their accounts. And under this new phenomenon of “shared employees,” a collusive pact between bosses has been born. The supermarket chain Fresh Hema, for one, issued an announcement that they had “borrowed” employees from Yunhai Cuisine and Youth Restaurant in Beijing. One after another, major business outlets chimed in to say that “flexible” employment had saved them―that “sharing employees” is a good solution. But is employing short-term, independent contractors actually a novel phenomenon? On the contrary, this employment practice has existed for a long time, and is merely becoming more and more common. Subcontracted workers have multiple employers, yet lack company benefits, and must pay for access to social services.

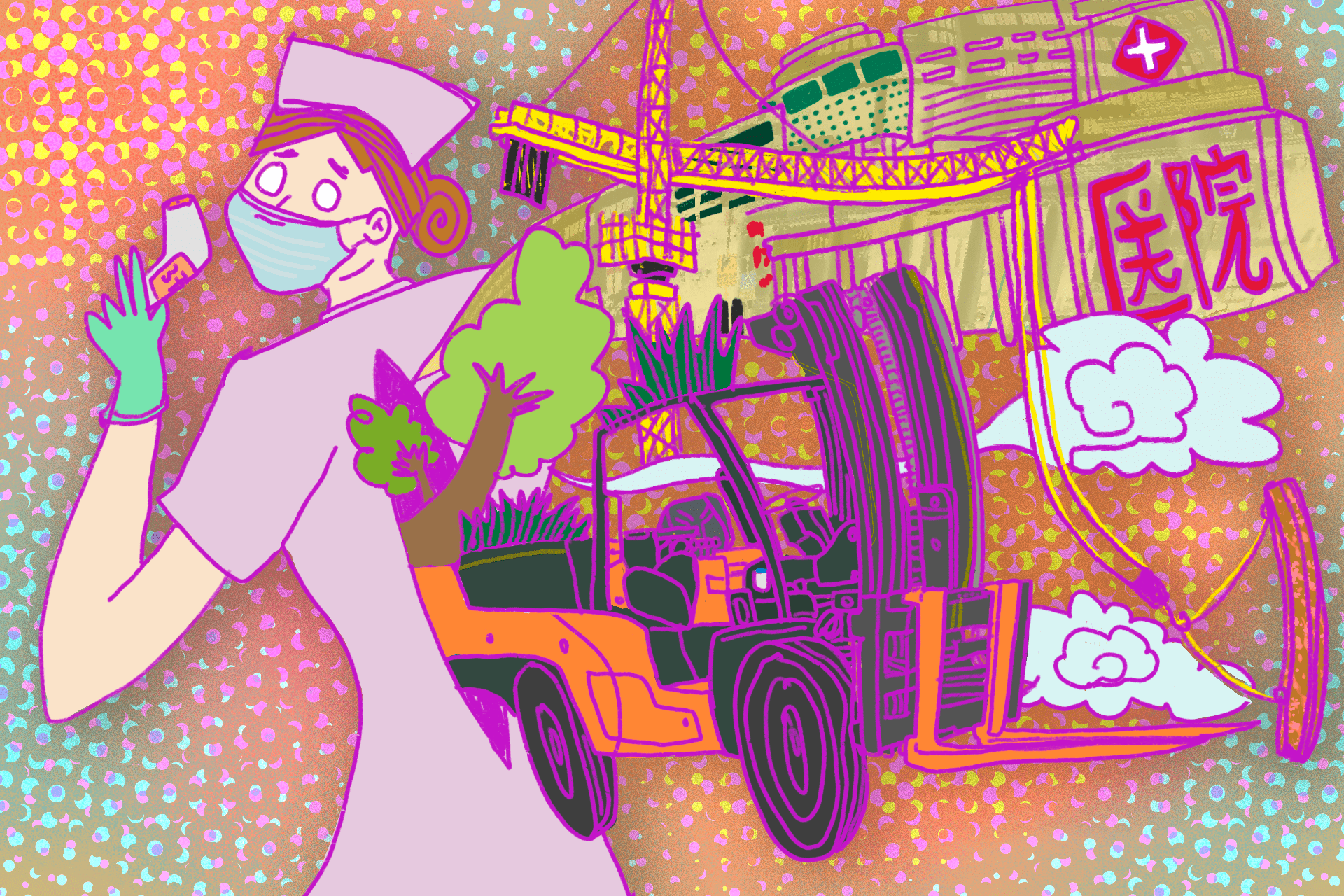

Apart from new social ailments, there are existing problems that have yet to be resolved. In order to boost the nationalist narrative, state media broadcasted live footage of Huoshenshan and Leishenshan Hospital undergoing construction. Construction equipment were given cute nicknames, and viewers were transformed into “cloud supervisors” and “fans” of the state. However, as the social media account “Wuyu” points out: “Is the worker doing the job, or is the forklift moving itself?” This kind of behavior alienates workers’ labor from the machines they are operating. It disregards the labor of construction workers and is misleading for younger viewers. What’s even more depressing is that bureaucrats would rather develop a platform for online users to admire the fictitious “Little Fork Sauce” than ensure that construction workers are paid on time and have access to personal protective equipment. As a result, at the Huoshenshan Hospital construction site, while state media indulged in a phallic display of nationalism, another dramatic incident unfolded behind the scenes: migrant workers who braved the risk of infection and worked day and night to complete the hospital demanded backpay from their chief labor contractor.

White-collar workers do not necessarily have it better off either. A China News report points out that although working from home greatly reduces the risk of infection, being on call 24 hours a day causes many employees to be physically overworked. Overtime without overtime pay can be extremely exploitative. The clocking-in software “Dingding” reports that by 15 February—the official return-to-work date—there were already 200 million users and 10 million enterprise organizations signed up to use the platform for remote work. This increase in the number of people working from home highlights the longstanding and serious problem of Chinese companies illegally withholding overtime pay. Moreover, when working from home, it becomes harder to track overtime hours―and even harder to get paid for them.

In these circumstances, the absence of a discussion on the level of civil society is keenly felt. We are left to either hope that corporations would follow the law out of their own conscience, or that the state would write laws to regulate all corporations. Here, workers are the invisibilized majority―puppets expected to obey orders, denied their own agency and autonomy.

Revisiting the dilemma of ‘civil society’

Some believe that, in China, the social has long faced a state of suppression or “squeezing out.” Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, as land reform and statist socialist transformations were being implemented, the overall trend in the countryside was that traditional social forces such as large clan groups and the rural gentry withered and eventually died out. City dwellers were progressively incorporated into the all-inclusive “work-unit” system. Soon after, a collectivization campaign began in the countryside, including “mutual aid groups,” “rural producers’ cooperatives,” and “people’s communes.” Despite the high degree of alignment between the state’s will to enhance economic strength and the people’s desire to improve their material lives, and hence the ruling party’s enormous appeal among “the masses,” individuals in these organizations lacked sufficient autonomy. The means of production were public properties, agricultural produce were subject to the state’s uniform system of purchasing and selling, and economic life was planned by the state. The grassroots base could not refuse many of the campaign-style orders, even if the orders were out of step with their actual circumstances, and the drawbacks of bureaucracy led to many disastrous outcomes. State power had extended into the daily lives of the grassroots.

In response to this situation, state leaders launched the Cultural Revolution and briefly attempted to re-mobilize society under the command of the party state: to break bureaucratic authority and institutional rigidity through social campaigns and political debates, and to form a popular participatory democracy. It ultimately led to large-scale political persecution and internal conflict among the masses. By the late 1970s, all the practices of the Cultural Revolution were discarded under the “eliminating chaos and returning to normal” (撥亂反正) program. On the one hand, the state took the construction of a market economy as a normative path towards modernization; on the other hand, it restricted open political debate on the grounds of promoting development and social stability, resulting in what the Chinese New Left intellectual Wang Hui has called the historical trend of “depoliticization.” Wang’s concept of “depoliticization” refers to the political ideology that prioritizes modernization, marketization, globalization, development, growth, etc., so much so that they became the dominant and hegemonic values. Abandoned in this process were political organizations, debates, and social movements motivated by different political values and interests, namely interactions among diverse political subjects.

In debates about civil society in the 90s, some intellectuals exposed their uncritical embrace of market-oriented institutional reforms, and hoped that the contractual relationships forged in a market economy could promote the growth of civil society (市民社会). Note here the blending of civil and urban in the term citizen (市民). For example, in Deng Zhenglai and Jing Yuejin’s article “Building civil society in China,” the authors consider “the entrepreneur class” and “intellectuals” to be the backbone of civil society, excluding the majority population of workers and peasants from this concept. This construct completely ignores the fact that the development of the modern market economy was predicated on a hypothetical separation of the political and the economic, whereas in contemporary China, market-oriented reforms have always been driven by the state. In fact, the four decades of reform and opening up make plain the fact that, in the process of marketization and privatization, the line between the power elite and the bourgeoisie is increasingly blurred. Under the dominant logic of “development is the only hard truth (發展才是硬道理),” the voices of different social classes, especially the lower class, are swallowed up in the discourse of “economic development.” Entrepreneurs and intellectuals not only failed to become the backbone of civil society, but are also colluding with state power. In any case, such a theory of “civil society with Chinese characteristics” has missed the point from the very beginning.

It is precisely in the homogenizing effect of the concept of ‘citizen’ that we see its limitations: the differences in class, race, and gender always prevent citizens from exercising the same rights and obligations.

We can take the history of social transformation in South Korea as an example to further shed light on the limitations of civil society. Civil society groups arguably spearheaded the entire process of democratization of South Korea from the 60s to the 90s. With broad participation from workers, peasants, student groups, intellectuals, religious figures, and other social classes, South Korea rejected authoritarianism and embraced democratic constitutionalism. The democratization movement also furthered the growth of social organizations, and allowed civil society to develop lawfully in Korea. But political democratization did not solve the problem of chaebol (family-controlled corporate conglomerates) monopolies.

The new democratic system could not effectively restrict the chaebols at all. Under the rhetoric of transitioning from a “state-led” to a “civilian-led” economy, the chaebols gained an even higher degree of autonomy, which exacerbated economic centralization and began to corrode the democratic system. Even though several post-democratization presidents had campaigned under the banner of “anti-chaebol politics” and were activists of humble origin, most of them eventually became embroiled in corruption scandals and were ultimately unable to battle the deep-rooted system of crony capitalism. That is why many consider South Korean democracy as plutocratic, a dilemma that has also profoundly restricted the progress of civil society. Post-reform civil society primarily operated through middle-class dominated social organizations. Civic movements became moderate and tended to uphold procedural democracy exemplified by the electoral system. Civil society, as a whole, risked degenerating into a game field between different interest groups: elite interests strongly influenced social movements, while social issues such as the widening wealth gap, the pressures of survival of the general populace, and the acute contradiction between labor and capital remained unaddressed after the financial crisis.

Let’s now turn our attention to Western European countries that have already “modernized” as well. If civil society is conducive to the project of modernization for “under-modernized” states, how do we account for the resurgence of civil society in European states since the 1980s and 1990s? In 1997, British sociologist Anthony Giddens, who advised the then Labor Party leader Tony Blair, put forward his theory of the “third way.” To some extent, the third way represents the contemporary Western theory of civil society. In order to relieve the heavy financial burden caused by the traditional welfare state and the social imbalances caused by neoliberal competition, Giddens advocated for decentralizing the government, vitalizing the communities, and encouraging bottom-up decision-making and local autonomy. As such, civil society seemed to mean reawakening the masses’ faith and interest in politics, emphasizing the equal importance of asserting rights and performing duties to the society.

Yet, the third way also implies certain compromises with neoliberalism. Shifting the focus of the welfare system from direct financial support, to training, education, and other investments in human resources as a means of “transforming welfare into jobs,” has significantly increased the difficulty for the masses to obtain social benefits. We can see the negative impact this policy has had on workers in the Palme d’Or winning film, I, Daniel Blake. It is precisely in the homogenizing effect of the concept of “citizen” that we see its limitations: the differences in class, race, and gender always prevent citizens from exercising the same rights and obligations.

In addition, the third way sidesteps concrete issues that discourage “citizens” from political participation, attributing their lack of participation moralistically to the lack of a sense of social responsibility. The third way even suggests transferring state power to strengthen institutions of global governance, neglecting the profound inequalities created by capitalist globalization. When Third World countries try to construct civil society following established international protocols, they will no doubt find that such a framework may not translate well for their local realities, and that power imbalances persist at the international level. Given that civil society does not deal with the disparities at the root of many social problems, it is unbelievable that it is regarded as a tenable means of even elite governance.

Curiously enough, since the new millennium, intellectual debates in mainland China around “the third sector” have essentially been an extension of the discussions about the third way. In Kang Xiaoguang and Wang Shaoguang’s “The development and future of the third sector in China,” Wang defines the third sector as organizations with these five characteristics: non-governmental, non-profit, organized, self-governing, and voluntary. According to Kang and Wang, due to “government failures” and “market failures” since the 1980s, the conditions that gave rise to the third sector in China were similar to those of the third way in Western European social democracies. In the Chinese context, the third sector supplements certain functions of the government, such as providing social welfare, social services, and employment. It can also train people to resolve daily conflicts using democratic means, thus nurturing a popular democratic tradition that may ultimately pave the way for political democratization.

In his response to Kang and Wang, Qin Hui points out that the Chinese and Western contexts are quite different. In the West, the third sector emerged to address the failures of the welfare state and to regulate the failings of market competition. Since the welfare state enforces the public good, and the free market allows individuals to compete for private interests―both of which are products of modernization―the third sector, which addresses problems of modernity, should therefore be considered “postmodern.” By contrast, the main task facing China is modernization, not post-modernization: China has neither established a democratic welfare state nor a free market for competition. China’s third sector thereby faces a government that “seeks private interests through compulsory measures.” Therefore, our priority should be to “restrict power,” rather than to help the government “shift responsibility and blame.” In this vein, Qin argues that China’s third sector should strive for social justice for marginalized groups, such as farmers, migrant workers, laid-off workers, retirees, the unemployed, the elderly, the weak, the sick, the disabled, and women and children. Not only should the third sector bring them charitable benefits, but more importantly should assist them in actively participating in rights based struggles. In China, it should be considered a huge achievement if the third sector remains free of interference from the authorities, let alone having the third sector take over government responsibilities.

At the core of this debate then is the autonomy of the third sector. The truth is, although the third sector is by definition non-profit and voluntary, the operation of mutual aid and self-organized groups still requires stable funding. At present, most third-sector organizations rely on donations for daily operations. However, depending on their sources, donations may undermine the autonomy of these organizations.

Despite all the debates, these scholars did not go beyond the existing framework of civil society in order to address its limitations. If the third sector is constrained financially, why can’t it explore an alternative economic model in order to achieve self-reliance? While this is also not easy, civil society can at least begin by vigorously intervening in the economic sphere with the goal of restructuring it. Another problem lies in the discursive concealment of violence in any discussion on civil society or the third sector: violence inevitably figures as an instrument of suppression or of anti-suppression. If the current theory of civil society does not address these problems, it will likely remain empty talk.

To be continued.

Revisit “Mutual aid and the rebuilding of Chinese society―Part 1” here.