Originally published in Made in China. Republished with permission.

For several months in 2019, the world’s news media was front-paging the Hong Kong anti-extradition bill movement almost on a daily basis. However, towards the end of the year, with the street violence subsiding and the fierce battles at two universities ending in the defeat of the students and their supporters, the international media seemed to lose interest. As global attention shifted elsewhere, one might have assumed that the movement had died a natural death. It did not. It is from here that this essay picks up the narrative. It was at that point that the movement branched off in a new direction, with activists beginning to set up trade unions and transitioning towards a nascent organised movement.

Disagreement in solidarity

In the wake of the Umbrella Movement, which ended in 2015, a whole host of small groups and political parties emerged alongside the ‘old’ pro-democratic political parties of varied political persuasions. This mushrooming led to competition and fragmentation, which in turn undermined the effectiveness of political activity. Wary of this lesson, the anti-extradition bill movement that began in earnest in June 2019, and eventually drew around one million people onto the streets, has been demonstrating unflinching solidarity to this very day. Differences have been put aside, and the movement has coalesced around three cohesive ideals.

The first can be found in the ubiquitous slogan ‘Five Demands, Not One Less’, a set of political demands broad enough to accommodate all political leanings. The second was a pact embodied in the saying ‘brothers climbing a mountain; each trying one’s best’ (兄弟爬山, 各自努力), meaning each adopts a strategy they deem best to achieve the goal while not criticising or intervening in the actions and strategies of others. This managed to bring together the two key blocs of the protest movement: the ‘Valiant Braves Faction’ (勇武派) and the ‘Peaceful, Rational, and Non-violent Faction’ (合理非派). The former is made up mostly of students and younger people, all geared and willing to confront the police head on. The latter is composed of people who either would not, or could not, engage in violence at the battle front and rather play supporting roles at the rear—for instance, providing material resources, organising or participating in rallies, joining peaceful activities like ‘let’s lunch together’ (和你lunch) or ‘let’s sing together’ (和你sing), raising funds, joining human chains, and taking part in a myriad of other innovative actions. To emblemise the unity of purpose of these two souls of the movement, a new Chinese character was even playfully invented, combining elements of the characters for ‘peaceful’ (禾) and ‘valiant’ (勇).

This movement was supposed to ‘be water’—that is, unplanned, unpredictable, fluid, and spontaneous, a form of urban guerrilla tactics with protesters suddenly popping up and disappearing in shopping malls and subways stations.

The third was an agreement that there is ‘no big table’, i.e. there are no leaders sitting around a table deciding the direction of the movement. Anyone could put forth proposals—really any idea and type of action—anytime and anywhere through the social media platform Telegram, which requires no real name registration from users. As the slogan goes, this movement was supposed to ‘be water’—that is, unplanned, unpredictable, fluid, and spontaneous, a form of urban guerrilla tactics with protesters suddenly popping up and disappearing in shopping malls and subways stations. At the same time, big rallies organised by the pro-democracy parties and well-established organisations continued to be well attended. The two-million-strong march that took place on 16 June 2019 was the largest display of the force of unity.

Trade unions in Hong Kong

As months of street actions did not extract any concession from the authorities, a part of the protest movement branched off in a new direction that was more formal and organised—it began setting up as-yet-small independent trade unions.

During three weeks in January, I was in Hong Kong to research these nascent unions. On that occasion, I conducted interviews at several recruitment stands that volunteers of these new unions had set up outside metro stations, busy street junctions, and at hospital entrances during lunch breaks, after work, and on weekends. I met with newly-elected members of some of the new unions’ executive (or preparatory) committees, attended a couple of union-organised labour law training sessions, and had meetings with Hong Kong academics and labour NGO staff. I also interviewed staff of established union federations in the city. Since January, I have kept abreast of events through social media and online conversations.

Hong Kong is a global commercial hub dominated by free-market beliefs with a relatively weak trade union culture. The largest union federation is the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU), with 253 affiliates and 420,000 members. It is well-resourced and largely controlled by the government of mainland China as a counterpart of the official All-China Federation of Trade Unions—a mass organisation subordinated to the Chinese Communist Party and the only trade union legally allowed to exist in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Just like its partner on the mainland, the HKFTU functions like a welfare organisation, doling out money and assistance to its pro-Beijing following. A competitive union grouping that has a long history is the Hong Kong and Kowloon Trades Union Council (HKTUC), which historically had political links to the Kuomintang regime in Taiwan and is now in steep decline. Both these union federations often have acted more like the political arms of their mentors than as unions.

Today, the federation that is most active in organising workers and assisting them in industrial disputes is the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU), which was formed in 1990 and today has 160,000 members in 61 affiliate unions. Inasmuch as it is not directly associated with a political party, it is an independent union federation that politically situates itself in the pro-democracy camp. The new unions have sought help and advice from the HKCTU, though the leaders of the organisation have resisted playing a leadership role over them, as they are hesitant to be seen as intervening in a new spontaneous trade union movement.

The new unions that have emerged over the past year did not start out as traditional unionising efforts. Instead, they arose from demands for political change in support of the protest movement, without any agenda regarding work conditions or wages. The earliest volunteer organisers emerged from professional sectors such as finance, accountancy, medicine, health, social work, and education. Nurses, doctors, and paramedics, as well as reporters at the front lines of the battles, repeatedly saw protesters getting severely injured due to violence from the police, with members of the security forces even rushing into hospitals demanding to interrogate injured protesters and accessing their personal records. These professionals themselves were often tear-gassed, pepper-sprayed, and beaten up for trying to help the injured and traumatised on the front lines. Some of them were also troubled that at their workplaces, pro-establishment managers harassed those who dared to show support for the pro-democracy camp. Feeling vulnerable, angry, and frustrated, discussing among themselves in person and through social media, these people began to seek peer support within their professional ranks, where they could share common experiences and make their voices heard.

From loose sand to a united front

The call by students and other young people to launch a general strike as part of the protests became the catalyst for forming new unions. Disappointed that their fluidly-organised ‘be-water’ street protests had not extracted any concessions from the Hong Kong government, in early August 2019 they took to social media to implore all of Hong Kong to stage a ‘Triple Strike’ (三罢), so called because it was supposed to involve workers, students, and businesses. On 5 August, the day chosen for the strike, some 600,000 people joined rallies held in different parts of the city. Supporters participating in the protests refused to turn up for work or called in sick. Once at the rally venues, some of the protesters organised themselves into groups by occupation or trade. This turned out to be an opportunity to discuss among themselves the strategy of participating in the protests by way of their occupational identity.

On 2 September, a second ‘Triple Strike’ was called, but this time only some 40,000 people turned up for the main rally. The fear of management displeasure had deterred many others. In her speech at the rally, Carol Ng, head of the HKCTU, referred to the disparate groups who attended as ‘sectors’ (界别) because the idea of forming new trade unions did not yet exist among them. However, some of the attendees began to discuss the possibility of creating a means to protect themselves from managerial harassment and reprisal through the creation of a collective support group. This led to the formation of a ‘cross-sectoral struggle preparatory committee’ (跨界别抗争预备组) and initial talk of forming unions.

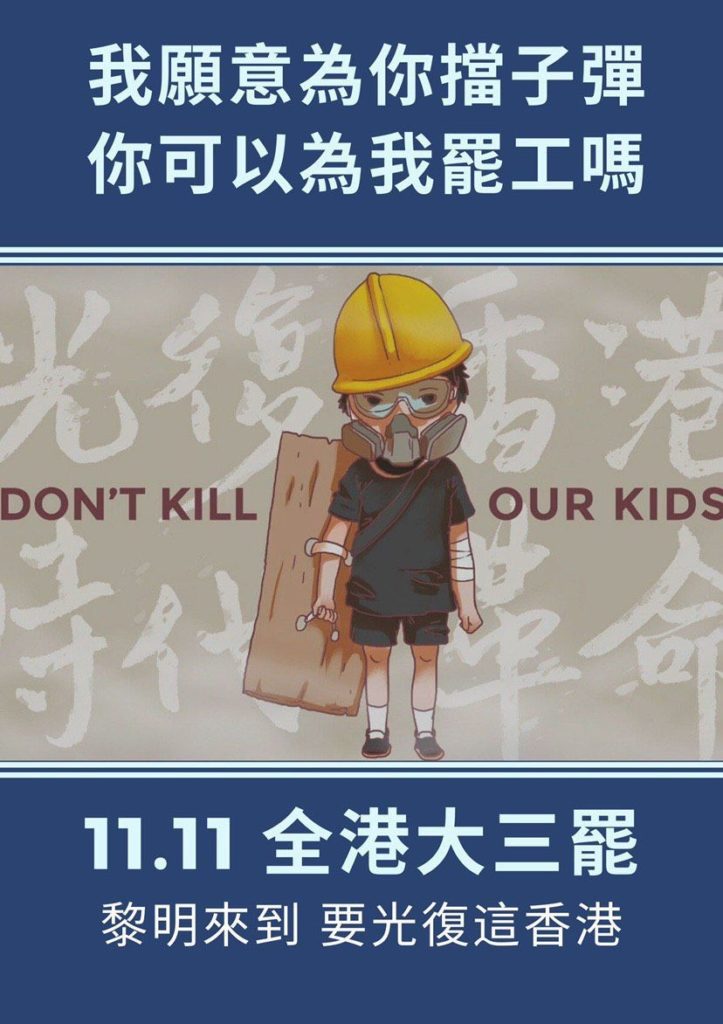

At the end of October, after the suspicious death of a Hong Kong University student who had fallen from a multistorey parking lot, angry activists wanted to call another general strike. Posters went up across Hong Kong, including a dramatic one that read: ‘I am willing to take a bullet for you. Are you willing to go on strike for me?’. This third ‘Triple Strike’ eventually took place on 11 November in many parts of Hong Kong, and ended in roadblocks and violence.

By then, a new umbrella group called the ‘Two Million Triple Strike United Front’ (二百万三罢联合阵线), appeared on social media posting news about forming unions and sharing new ideas about possible strategies. This time, they argued, a general strike had to be better organised at the workplace level and needed to be large and strong enough to force the hand of the Hong Kong government. Since then, the group has evolved into an umbrella organisation for the new labour movement in Hong Kong. The first urgent task for the nascent trade unions was to recruit more members. To attract more attention from the public, union activists set up ‘joint union stands’ (联合跨站), each hoisting the flags of their unions. At a mass rally on 1 January 2020 in Wanchai district, the emerging unions coordinated their activities, and representatives from a number of them stood together for a photo, each with their own union’s flag and holding a joint banner bearing the slogan ‘Trade Unions Resisting Tyranny’ (工会抗暴政).

As most of the founding members of the new unions had little conception of trade unionism or relevant labour laws, they began to invite labour lawyers and HKCTU leaders to give seminars and training sessions. According to Hong Kong’s labour law, political strikes are illegal, and so understanding the legality of strikes and how to strategise became a major concern. Moreover, through the training sessions and in the process of registering their unions with the government, organisers were exposed for the first time to various aspects of workplace rights, including trade union rights. Gradually, the motivation for setting up unions became multidimensional, rather than a single-minded focus on supporting political strikes. In addition to the five major political demands, trade union leaflets also included demands for shorter work hours, higher minimum wage, better benefits, fairer bonuses, and, not least, collective bargaining rights.

Unexpectedly, the new unions that first got organised and registered represented white-collar professions, such as the accountancy union, the financial sector union, the new civil service union, and the health sector unions. When I commented ‘I’m surprised that you are interested in setting up a union since you are from the middle class, and not workers,’ several interviewees retorted: ‘No, we are workers.’ One of them even emphasised: ‘There are only two types of people—bosses and workers. We are workers.’

Sometimes, without being asked, interviewees poured out their grievances. Housing was a recurring grudge. When apartments of 50 square metres fetch as much as five million HKD, even those with a university degree cannot afford to rent, much less buy a house. Over the past couple of decades, as living costs continued to rise and inequality widened, traditional middle class professionals have started to take on a working class identity. A second grievance had to do with occupational health and safety. As the coronavirus began to spread to Hong Kong, staff in the accountancy sector sent by their firms to audit client companies in China had serious complaints about the lack of regard for their occupational safety. Finally, a few complained to me that their own sector of the economy is increasingly dominated by PRC-owned businesses, or that at their workplace Hong Kongers have to compete for jobs and promotions with educated immigrants from the mainland, and that their bosses favour the Chinese staff because of their connections with mainland businesses.

Unions participating in electoral politics

At the end of November, the nascent unions set their sights on a new goal after the pro-democracy camp unexpectedly achieved a landslide victory in the District Council elections, winning 17 out of 18 of Hong Kong’s district councils. In the past, the pro-democracy camp had never seriously competed in these local elections, dismissing the councils as powerless and not worth investing time and money in. Since 2007 the councils had been dominated by the pro-establishment camp, but in late 2019, after half a year of street protests, channelling efforts into electoral politics suddenly became an option. The district elections triumph was a big morale booster. If the protest movement had won this election, they might be able to take a meaningful number of seats in the next two selections: first for Hong Kong’s partially-elected legislative council (LegCo), which is scheduled to take place in September 2020; and second, for the committee that selects the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, which is expected in June 2021.

Some of the seats in both bodies are apportioned to trade unions as one of the ‘functional constituencies’ that make up their membership. For years, these seats had been dominated by the pro-Beijing HKFTU, which, as stated earlier, has a large number of affiliates. Before 2019, the HKCTU had not put its energy into organising and registering new unions to compete within this functional constituency for a number of reasons. First, it did not have resources to outcompete the HKFTU, and so regarded any attempt as a waste of time. As a union, it preferred to prioritise workplace issues and the protection of labour rights, two aspects that the HKFTU had always neglected. Second, with the territory being dominated by a neoliberal capitalist ideology, Hong Kongers had thus far shown little interest in trade unionism. An HKCTU staff member noted that at the beginning of the anti-extraction bill protest movement, few protesters cared to take the handouts she distributed.

In the first three months of 2020 there were 1,578 applications [to form a trade union] as opposed to just 10 to 30 in previous years.

Surprisingly, though, the procedure to form a new trade union in Hong Kong is simple. The minimum requirement is that seven people turn up at the Labour Department to apply to register a new union, formed either by trade, sector, or occupation. These initial seven organisers have to fill in forms stating the mission of the new union. Getting official approval usually takes about a month or two. Once approved, the founders have to hold a general meeting to elect an executive committee and the new union is then formally registered. Organisers assured me that the Labour Department staff were helpful and that they had not encountered attempts to make registration difficult. This ease in registration explains the proliferation of newly-registered pro-protest trade unions in a few short months. In fact, some activists started a program called ‘7 UP’ calling on those who could gather seven people to apply to set up a union. The Hong Kong and Chinese governments had been too confident that the pro-Beijing camp would continue to monopolise the labour scene, since Hong Kongers had never expressed much interest in joining unions.

The first of the two forthcoming elections is the Legislative Council election scheduled for September 2020. For the functional constituencies, the labour sector is apportioned three seats out of 35, which, as I mentioned above, have always been dominated by the pro-Beijing camp. Since each union is given one vote under a winner-take-all system, it means that unless the democratic camp increases the number of pro-democracy trade unions, the pro-Beijing camp, having a larger number of unions, will again win the three LegCo seats. Unfortunately, to be eligible to vote, a union has to be set up at least a year before the election. Since the wave to establish unions did not begin in earnest until October/November 2019, this means that the new unions will not be allowed to vote in the forthcoming election. In spite of this, from June 2019 to February 2020 there have been 735 applications, followed by another ‘tsunami’ of requests since then. According to official data from the Labour Department, in the first three months of 2020 there were 1,578 applications as opposed to just 10 to 30 in previous years.

Although many of the new unions will not be able to participate this September, they will be eligible for the vote on the Election Committee in June 2021. The Election Committee, consisting of 1,200 seats, will in turn vote for the Hong Kong Chief Executive in 2022. The labour functional sector will be given 70 seats. Here too, the more pro-democracy unions there are, the better the chance they have of winning a majority. Sadly for the pro-democrats, the pro-Beijing camp has also been racing to set up new unions. Whether the pro-democrats can gain a reasonable portion of the 70 seats will depend on whether the various tendencies in the movement can coordinate to avoid running against each other. It is also worth mentioning that alongside setting up new unions, there is also an ongoing, extremely well-organised campaign to increase voter registration.

A test of union solidarity

The test of whether the leaders of the new unions that sprouted up during the protests—people who only a few months earlier had little conception of trade unionism—could withstand political and management pressures presented itself at the end of January 2020. The coronavirus was spreading rapidly inside mainland China and beginning to penetrate Hong Kong, which was not prepared to fend off the pandemic. Hospitals were short of beds, personal protective equipment, and personnel. At that time, the newly-formed Health Authority Employees Alliance (HAEA), which had been actively recruiting new members and by then had 18,000 union members out of the 80,000 medical and health personnel in the city, called on the government to close the border with China out of concern that the territory’s hospitals would be overwhelmed, putting medical staff at risk. In other words, the protest was over an occupational health and safety issue, one of the key workplace issues on which trade unions generally focus.

On 31 January, Carrie Lam refused, stating that this would mean discriminating against PRC citizens. The HAEA executive committee, led by a young chair who openly admitted that only half a year earlier she had only cared about enjoying a good life and had no idea about trade unionism, proposed to engage in a two-stage strike. With 3,123 voting yes out of 3,164 ballots cast, the members’ vote on 2 February was nearly unanimously in favour of the proposal. More than 50 unions then came forward to support HAEA, and on 3 February, the first day of the strike, 7,000 members participated—i.e., 17 percent of Hong Kong’s hospital-related medical sector. The same day, Carrie Lam announced all but three border crossings with the mainland would be shut, with some restrictions on entry by other channels, but refused to budge further.

When the first stage of the strike ended after five days, HAEA called for a second vote on whether to continue the mobilisation. Going on strike always invokes an intense moral dilemma for medical professionals, and this time, with only part of their demands met, of the 7,000 who cast votes 60 percent voted against keeping up the strike, and the action was called off. Nonetheless, we can still say that it was a partial success as Carrie Lam ordered the closing off of most of the entry points to Hong Kong from China. The strike was an impressive first action, led by a new generation of trade union leaders who had quickly learned how to organise and, above all, were committed to trade union democracy.

Though compared with other regions Hong Kong has been able to control the pandemic quite well, as the coronavirus continued to spread, street activities in the city declined. The new unions continued to recruit members and to make preparations in sight of the November election. Meanwhile as suppression continued in workplaces members have swiftly sought help from the unions—particularly in the education sector, where teachers are increasingly under pressure to accept new pro-PRC curriculums, harassed, or even fired for supporting the pro-democracy movement and for not discouraging their students from participating. However, this new focus on workplace issues has not changed the political agenda. On 20 June, 30 unions joined hands to organise a referendum to seek members’ approval to go on another general strike in protest against Beijing’s plan to enact a National Security Law for Hong Kong. A new slogan reflecting the collective identity of the new Hong Kong trade unions appeared: ‘To Liberate Hong Kong, Join the Union; Union Revolution to Resist Tyranny’ (光复香港, 加入工会; 工会革命, 对抗暴政). Of the 9,000 union members who voted, 95 percent said yes. However, given the high abstention rate the strike was called off.

After this, the unions shifted the focus of their activities to the primary election organised by the pro-democracy camp to decide who should stand in the LegCo election in September. On 11 July, 600,000 people cast their votes to elect their favourite candidates for the functional sector to which they belonged. At the time of writing, the votes are still being counted, but there is at least one encouraging sign for the unions. The HAEA Chairperson who had organised the strike in January won by a landslide, receiving 2,165 votes out of 2,856, against the 186 votes for the current legislator for the health service sector. If allowed to grow and mature, organised collective action could have a future, especially now that the ‘valiant faction’ has lost the prowess that it displayed earlier in the movement.

What next?

In sum, when the Hong Kong government did not yield to the pro-democracy protests, a section of the protest movement started a labour movement, building up new small trade unions. Unlike the deliberately leaderless movement in the streets, the new shift meant taking an institutional route that requires planning, organisation, and even a link to electoral politics. There are now two strategies running in parallel with each other: the front-line protest movement facing off against the police, and a second aligned movement that is building organised institutional structures—among them trade unions. This multi-pronged thrust has not created divisions within the protest movement. As the popular slogan ‘brothers climbing a mountain, each trying one’s best’ made clear, all of the trajectories are beneficial to furthering of the movement’s goals. This climb began by making strictly non-materialist political demands as part of the pro-democracy movement, but is now gradually also turning to materialist demands such as workplace conditions, wages, bonuses, and occupational politics aimed at securing a voice in the city’s flawed political system. However, with the passing of the Hong Kong National Security Law on 1 July, Hong Kong was turned overnight into a lawless society. In light of the direct oppression from Beijing, could the emergence of this trade union movement be a mere flash in a pan?

Anita Chan is Visiting Fellow at the Political and Social Change Department, the Australian National University. Prior to that, she was Research Professor at University of Technology Sydney. Her current research focuses on Chinese labour issues. She has published widely on Chinese workers’ conditions, the Chinese trade union, and labour rights. She is the co-editor of The China Journal with Jonathan Unger