Original: 【香港設計職人工會:政治抗爭和勞工權益並行】, published in 蹲點 Squatting

Translator: E’n

If you would like to be involved in our translation work, please get in touch here.

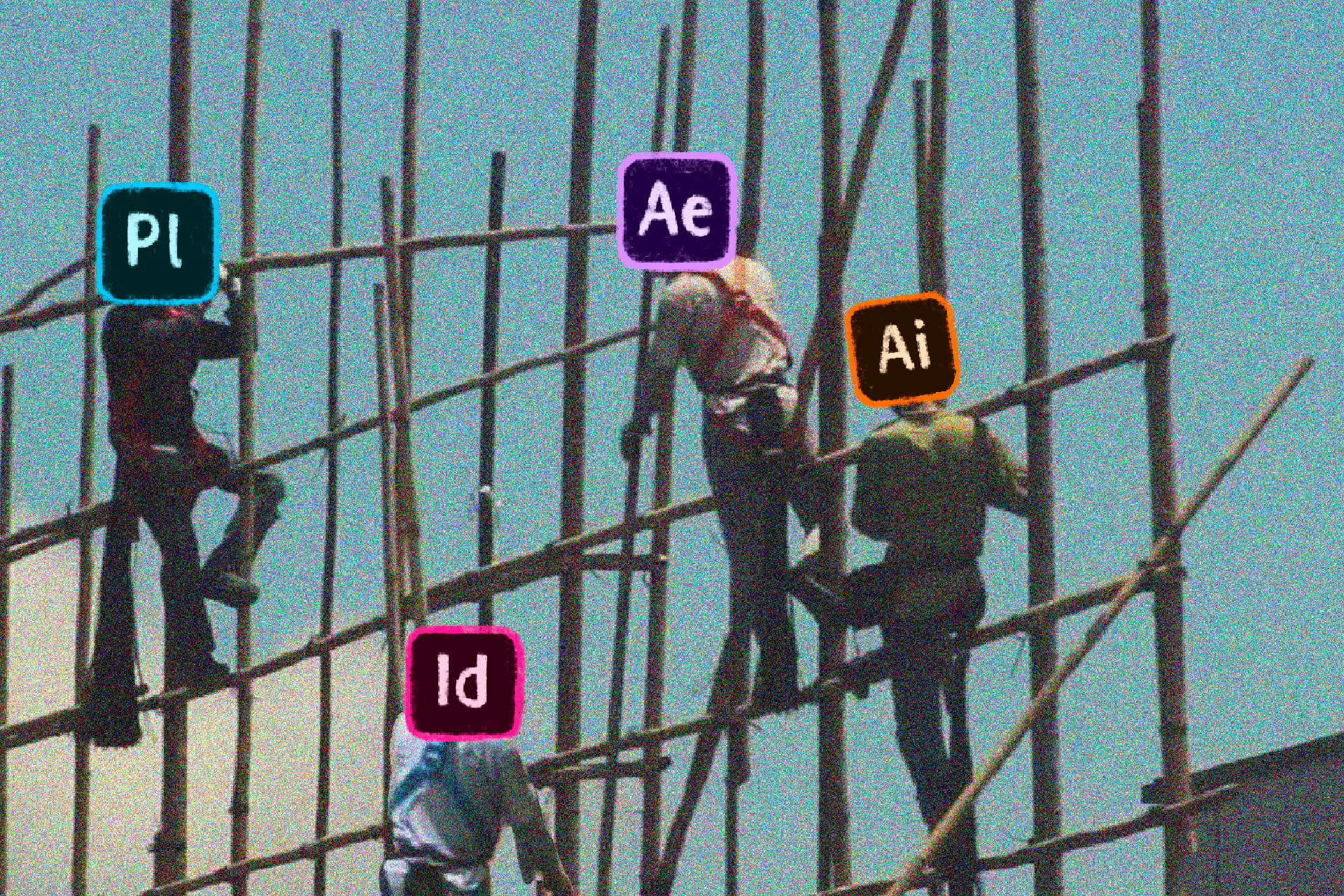

For many of my friends who are design workers, this is a common complaint: “Hong Kong designers have ‘no status.’” This lack of status means not only that design professionals are not getting enough respect in general, but also denotes a common conception of design as a field for those who don’t do well in school and can’t get a better job; a lot of people think that design is something that everyone knows how to do. It is widely known that the intensity of design work and remuneration for this work are extremely disproportionate. In fact, most designers work overtime without any compensation. Squaring the working hours with design workers’ income, hourly wages often do not even meet the current legal minimum wage (HK$37.5 per hour; about USD$4.80)

When design workers encounter these situations, many of them just put up with it in the hope that they could make a name for themselves one day and establish their own studio with its own style and following. Not many people have tried to fight for their rights at work or organized their co-workers. Like many ordinary Hong Kong people, they think unions are out of fashion, relics of resistant organizing centuries past.

However, since the calls for the three strikes (三罷)—work, school, and market strikes—last year, the union has made a comeback in the public sphere with a focus on its usefulness in the context of anti-establishment struggle. Since December 2019, it has been proposed that “peaceful, rational, non-violent” (和理非) demonstrators should form a trade union to support the movement, so that the union can not only mobilize larger masses to participate in the strike, but also to exert political pressure through economic means. They can also enter the functional constituency elections within the system and gain a steadier foothold in electoral politics, effectively unlocking a new front of resistance for the movement. While there had only been 11 new union registrations in November 2019, applications increased to 109 by December. In early 2020, the Labor Department received 600 new union registrations. The Hong Kong Design Individuals Union is one of them.

There have been more than 700 new union registrations from December 2019 to February this year. (We do not have exact figures for how many unions have been established in total.) After the first general membership meeting on March 21st, the Hong Kong Design Individuals Union was able to form its first stewarding committee. The initial call for unionizing perhaps aimed to mobilize a wider range of industrial actions to ultimately contribute to the pro-democratic movement in Hong Kong, but organizing design workers also means finally confronting labor issues within the industry.

The fight for democracy is not going to be won overnight, nor is the establishment of unions the be-all and end-all of worker struggle.

In addition to the design industry, other labor unions that emerged in this unionizing wave have found themselves more or less aligned on the basis of rampant problems long faced by Hong Kong workers. In the Design Individuals Union, an elected steward gave a speech that echoed existing voices in the movement: organized labor is a form of resistance. This kind of resistance has two goals: First, a larger pro-democratic movement is calling to support political resistance with industrial action; second, it aims to represent the interest of members and to fight for the rights and interests of all workers. This dual objective has also been incorporated into the union’s bylaws.

The Design Individuals Union also conducted a survey: less than a quarter of members (52 people) stated that their employment contracts have relevant terms and conditions regarding overtime pay, and some have claimed that working hours on a per week basis approached as high as 120 hours. In addition to the heavy workload, the creative industry in which designers work has also become the most egregiously reliant on precarious labor in recent years. Freelancer’s rights are not guaranteed, and workers at design agencies are often faced with delays in remuneration. In addition to using labor organizing as a means of resistance in the movement, the Design Individuals Union has placed widespread concerns, from standardized working hours to overtime compensations, on its working agenda.

The protests seem to be showing signs of fatigue. The epidemic is probably to blame, but this is far from an indefinite hiatus. The streets have quieted down, but rather than bring the movement to a standstill, the current moment of respite is providing much needed space for the development of more powerful, more enduring ways of struggle. Unions will open up a new front of resistance, but we shouldn’t think of their emergence as only instrumentalized toward the ends of electoral politics and the mainstream movement at large. The vision and energy of these organizers is not limited to resistance on solely the political level. While the seeds of the current momentum in worker organizing are rooted in the protests, new unions must be committed to fighting for workers in order to ensure their continued mobilization in the process of political and economic struggle.

For the left, this nascent rediscovery of organized labor may be serendipitous, but transforming this pivot into sustained commitment to worker organizing requires careful cultivation in the long run. After all, the fight for democracy is not going to be won overnight, nor is the establishment of unions the be-all and end-all of worker struggle.