Editors’ note: yehua is an activist who has been involved with social movements in Hong Kong, and has documented stories of Hong Kong’s migrant domestic workers.

The following are their comprehensive reflections of the 2019 Hong Kong protests, now in their fourth month. They carefully reconstruct the movement piece by piece, exploring its underlying motivations and contradictions, describing its accomplishments as well as missteps, while offering constructive suggestions.

Writing from a left perspective, they question the movement’s reliance on the identity politics of the “true Hongkonger,” seeing it as a form of liberalism in disguise that prevents vital structural change. Observing that protesters are growing increasingly fatigued, they make an urgent and compelling argument that there is hope for the movement to regain momentum, grow, and even “win”—if it can articulate broader demands that identify and challenge Hong Kong’s systemic injustices.

Introduction

It started with a million-strong demonstration against the proposal of the Extradition Law Amendment Bill four months ago. The protests—cheekily termed “no to China extradition,” which in Cantonese sounds the same as “don’t send us to our funeral”—quickly morphed into a movement with Five Main Demands against the state at its core: to formally withdraw the Bill; to retract the classification of the ensuing protests as riots; to withdraw all charges against protesters; to thoroughly investigate the police’ abuse of power and hold them to account; and to immediately implement universal suffrage for both the Chief Executive and the Legislative Council.

What happened in the weeks that followed could only be described as extraordinary and inspiring, notwithstanding their limitations. Between building countless “Lennon Walls” with messages of solidarity across the city, breaking into the Legislative Council and displaying a defiant banner denouncing the state’s tyranny, launching a grassroots media campaign to raise awareness of police brutality, organising “non-cooperation actions,” strikes, and class boycotts, while repeatedly braving mace and rubber bullets in direct clashes with a para-militarised police force, the current movement is extraordinarily inventive in experimenting with different strategies and facilitating diverse forms of participation.

But when it comes to directing these strategies towards specific, concrete, and transformative goals, the movement has unfortunately fallen short. The first four of the “Five Main Demands,” while important and broadly supported within the movement, are nevertheless limited to short-term concessions, and go little in the way of challenging Hong Kong’s underlying distribution of power and resources. Even considering the fifth demand, for full universal suffrage, there remains a reluctance to elevate the movement from a largely political struggle—concerned with defending civil liberties, the rule of law and the city’s autonomy—to a struggle that centres distributive justice, questions institutional power, and breaks open the identity of “the Hongkonger.” This is not wholly unexpected of a movement in Hong Kong, with its entrenched neoliberal culture that has lately taken a nationalist turn. Yet it poses important questions about how far this movement can go, who it sees as its subjects, who it appeals to, and what changes it may ultimately engender.

In this space, I hope to take stock of what has been happening over the past four months, and 1) pick out progressive practices that should be applauded and nurtured; 2) identify regressive elements and analyse how they can be countered; and 3) suggest strategies the movement should consider adopting along with the demands I believe it should articulate.

Ultimately, I hope this exercise can encourage friends and comrades to think about two questions: how can this movement be sustained, and how can it win?

The lurking Chinese state

In some sense, it was surprising that the Bill would ignite such widespread wrath, given that it would, strictly speaking, have the greatest impact on the people whose lives take place across the border: a small section of Hong Kong’s population. The official narrative seemed to confirm as much: the rationale for the Bill was to fill a legal loophole that would allow authorities to extradite a murder suspect to Taiwan for prosecution, targeting only those who break the law elsewhere (including Mainland China) and flee to Hong Kong. The Bill, the government was keen to assure us, would not create a Big Brother state to police our every move and persecute us arbitrarily.

There remains a reluctance to elevate the movement to a struggle that centres distributive justice, questions institutional power, and breaks open the identity of ‘the Hongkonger.’

Such rationalisations fell on closed ears, however, and very quickly it became clear that the mass mobilisations that began in June have more to do with protecting civil liberties and Hong Kong’s political autonomy from the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) encroachment than opposing the Bill itself. The timing was a key factor, as the anti-extradition protest that kickstarted the current movement happened just days after the annual vigil commemorating the martyrs of the Tiananmen Massacre. These days, there is a deep current of fear in Hong Kong regarding the CCP, and on the back of the June 4 candlelight vigil, these emotions were riding even higher.

I believe it is appropriate to understand “China-paranoia” as one of the dominant currents of the movement. We cannot overlook the fact that the images of a bloodied Tiananmen Square are still fresh on the minds of older Hongkongers; younger generations who did not witness the events nevertheless “remember” it as an irredeemable crime against humanity. A significant part of Hong Kong’s self-understanding centres around this trauma, reaffirming the idea of Hong Kong as a haven of liberty in contrast to the Mainland’s totalitarianism.

It was within this context that the argument against the Bill gained its main persuasive force: that it would signify the death of “One Country, Two Systems,” and reveal our government as no more than a puppet of the Chinese state. This helps explain why Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s overdue decision to withdraw the Bill in September did not dent the momentum of the movement at all; the damage had already been done. The very proposal of the Bill, her evasive and dismissive attitude in the face of massive protests, and her endorsement of the brutal police crackdown confirmed protesters’ worst fear—that Hong Kong’s government had become merely a conduit for the CCP’s interests.

The nativist right’s foothold

Given the decidedly localist/nativist turn in Hong Kong’s politics over the past few years, it is remarkable that this “China-paranoid” movement has not developed full-blown anti-Mainlander tendencies. Part of this is due to the right’s political failure: In the infighting that followed the Umbrella Movement, the right (especially those of a separatist bent) organised themselves, formed political parties, won seats in the Legislative Council, then were disqualified just as quickly from the Council, becoming marginalised and discredited again. While many in the current movement still feel attachment to Edward Leung, a separatist right-wing leader and the originator of the slogan “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times,” this attachment is arguably an emotional response to his ongoing imprisonment for his involvement in the 2015 “fishball riots,” rather than an outright subscription to his beliefs.

Concurrently, credit is due to those in the movement who have recognised the need to stand with and not against Mainlanders. These include activists, citizen/independent media initiatives, and community organisers, who have helped shape the movement’s discourse through LIHKG and Telegram—the anonymous and fairly open platforms where much of the movement’s organising has been conducted. Mainlanders, they argue, bear the brunt of digital authoritarianism and everyday state violence—two key pillars of the CCP’s 21st-century governance—and are themselves victims of a grossly imbalanced and undemocratic economic development agenda spearheaded by the Chinese state-capital nexus. These ordinary Mainlanders should not be held responsible for the wrongs their government perpetrates.

Tracking discussions on the aforementioned platforms, I have observed that while some users have proposed the movement’s main demands include nativist policies—such as reducing the immigration quota for Mainlanders or even blocking them from entry—others have responded that the real blame lies with the Chinese state and the uneven distribution of land and housing resources in Hong Kong. When some users accused Mainlanders of being submissive to the CCP’s oppression, others countered by citing conversations they had with Mainlanders to demonstrate that many Mainlanders understood and supported the movement in Hong Kong. When some users used slurs to address immigrants (especially Mainlanders and South Asians), others denounced their use and called attention to how many immigrants have been involved in the movement despite their routine exclusion from society and their neighbourhoods. In July, a group even organised an action near West Kowloon’s Express Rail station—which connects Hong Kong with Guangzhou and Shenzhen—hoping to explain the motives of the movement to Mainland visitors and to enable accurate news of protests in Hong Kong to travel back with them.

But neither has xenophobia been vanquished. One must not forget that when protesters stormed into government buildings in early July, one group deliberately targeted the storey in the Immigration Department that processes immigration applications from the Mainland. Nor should one forget that an action to “restore Tuen Mun Park,” supposedly intended to protest the Leisure and Cultural Services Department’s poor management of noise pollution from “dancing aunties,” ended up directly targeting the female Mainland immigrants, who were verbally assaulted with misogynistic slurs accusing them of prostitution; one was even trapped in a public toilet by the protesters. (There exists a very strong moralistic and cultural stigma against sex work in Hong Kong.) Regardless of the protesters’ motivations, we must not assume the movement has outgrown its right-wing impulses.

Resisting xenophobia

There are reasons to be optimistic about countering nativism. The fear over the Extradition Bill and its perceived threat against Hong Kong’s civil liberties broke up the right wing’s domination over the public narrative, by redirecting anxieties away from Mainlanders and toward the Chinese state and the inept Hong Kong government. This has offered a window for the left to advance some key arguments.

First, to counter the false impression of “immigrants taking resources away from locals,” we must continue to provide analysis of the chronic underinvestment in vital public and social resources that has created scarcity in the first place. Obvious targets include the extremely limited growth in affordable public housing—which lags far behind demand, with the average wait now exceeding five years—and the inadequate policies combating property speculation (especially what the marketisation of subsidised housing means for the more economically vulnerable in society). Another key issue is the glaring lack of public childcare services, which leaves single parents and workers in precarious jobs—including many new immigrants from the Mainland—reliant on social security to support themselves and their children, for which they face undeserved ire.

Regardless of the protesters’ motivations, we must not assume the movement has outgrown its right-wing impulses.

Second, we must broaden the movement by bridging it with other struggles. This includes the labour movement in Mainland China, the last line of defence for grassroots and migrant workers who, despite their invaluable contribution to China’s economic rise over the past decades, remain in terrible working conditions. They are routinely overworked but underpaid, poorly protected from occupational health and safety hazards, and often do not receive the various forms of social security and/or compensation to which they are entitled. They often resort to strikes and other forms of direct action to defend their rights as the legal apparatus protecting them is flawed and the authorities tend to side with capital interests. Indeed, the difficulty of winning workplace justice in Mainland China is not dissimilar to that which many Hong Kong workers are facing. And with more cross-border investment and business ventures, as well as the Chinese economy’s continued reliance on Hong Kong’s financial systems and global connections, it would not be a stretch to say that workers in Hong Kong and the Mainland are in the same boat and have the same enemies: owners, mega-corporations, and a class of professional and political elites who live off their labour, leeching away the wealth they create and denying them justice.

The fact that the movement in Mainland China has been facing intensifying repression in the past decade in the form of mass imprisonment of lawyers and human rights defenders, as well as the detention and “disappearance” of many labour NGO workers, journalists, and student activists, should sound alarm bells for Hong Kong. Moreover, it should spur workers and their advocates to defend their and Mainland workers’ rights, while there is still some space in Hong Kong for the movement to grow stronger and challenge the joined forces of capital and the state.

Connecting with migrant workers

Inside Hong Kong, the movement should look to connect with migrant domestic workers, a community fighting relentlessly for basic rights and workplace safeguards that have long faced difficulties with organising on a scale large enough to force concessions, due to the irregularity of their rest days, the lack of space to organise, and mainstream society’s readiness to turn away from the issues they face.

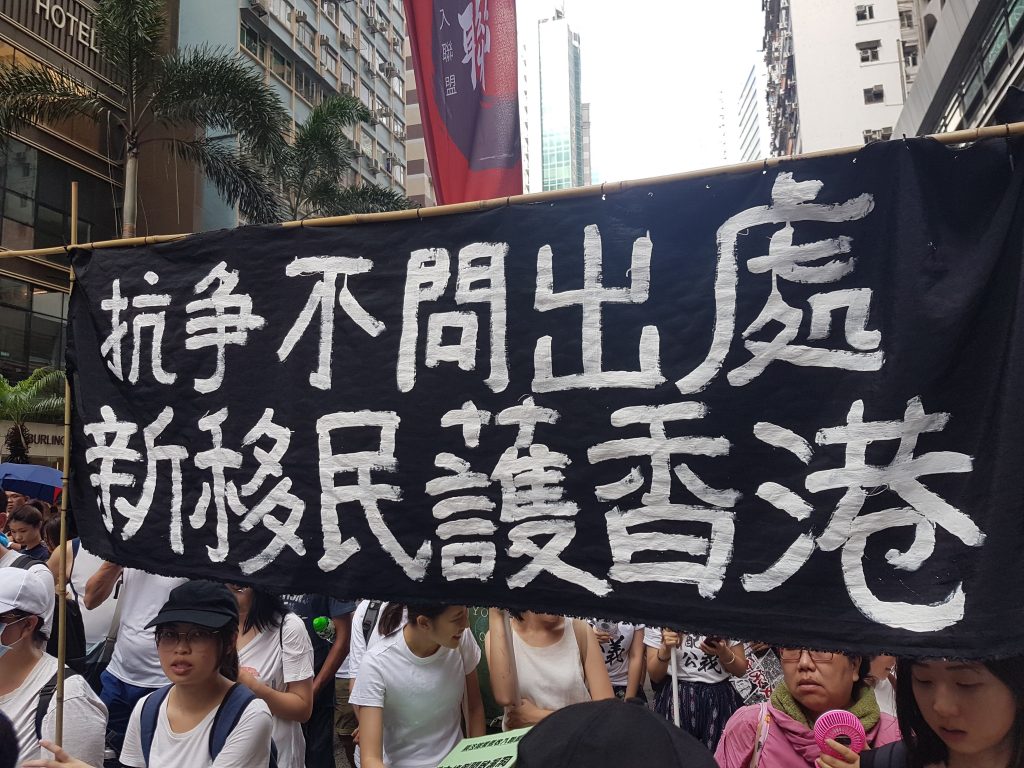

Indeed, during the past few weeks of protests, signs like the one shown above have been found in areas where migrant domestic workers frequently spend their days off on multiple occasions. Some users on LIHKG—likely triggered by the police’s increasing reluctance to officially permit assemblies—even naïvely pointed to migrant workers’ seemingly free use of public spaces with the police’s refusal to protesters as “double standards.”

Taking aim at migrant domestic workers shows the movement’s caricatured understanding of the community and their lives. In reality, migrant workers are often reprimanded by security guards and management staff to “tone down” their activities in public spaces, even though they are mostly resting and socializing. It also betrays the community’s proud history of struggle: migrant workers have been active in the labour movement for a long time, from partaking in 2005 anti-WTO protests, supporting striking dockworkers in 2013, to campaigning for a living wage for all workers in 2019. In the last few months, migrant workers have found themselves in the line of fire as the protests spread across the city.

Hong Kong’s unjust live-in requirement for migrant workers means they can only regain control of their bodies and lives when they leave their employers’ residences; with their low salaries, they can hardly afford to rent private spaces. Their occupation of public spaces is, therefore, a political act in itself. For years, workers have used spaces such as parks and pedestrian bridges not only for recreation, but also run stalls to organise workers and provide counselling and support for those in distress and/or abused by their employers.

Now would be the ideal moment for the left to encourage the movement to understand the issues faced by migrant workers and to stand with them in their struggle to protect their rights—instead of chastising the already vulnerable.

Rethinking the ‘Hongkonger’

A collective consciousness, in which people see themselves primarily as citizens and as Hongkongers, is firmly entrenched in the movement. This form of subjectivity is not only manifested in the daily “Hongkongers, add oil!” or “Hongkongers, resist!” chants, but also the movement’s liberal rhetoric around defending the “rule of law,” “One Country, Two Systems,” and “human rights.” In sum, the identity politics of “the true Hongkonger” has become fused into the movement, with very little space for dissecting what this actually means.

This is problematic for a few reasons. The first is that it lays a foundation for xenophobic, right-wing politics. These identity politics end up determining who the movement counts as part of Hong Kong’s public; in other words, who is deserving of democracy and better rights protections. But labels like “Hongkonger” are exclusionary by nature, because they are inevitably defined against a foreign “other.” It almost invariably excludes Mainlanders (especially Mainland immigrants), but it also often excludes Hong Kong’s non-Han Chinese minorities—particularly South Asians—who are frequently stereotyped as unassimilable, dirty, and involved in organised crime. If Hong Kong’s protest movement were to truly “win,” would these groups be included in Hong Kong’s democracy?

Some dismiss this argument by pointing out that some members of Hong Kong’s minority communities “proved themselves to be true Hongkongers” by supporting and participating in the protests. But we should be wary of such conditional acceptance: Who has the right to decide what makes one a true Hongkonger? What do we do with those who do not fit those criteria? What about South Asians in Hong Kong who are routinely targeted, harassed and brutalised by the police, who arguably have longer-standing reasons to join in a movement against police brutality, but who are nevertheless ambivalent about the movement because none of its demands is directly relevant to their community’s needs? If those supporting the movement have a different idea of what social justice looks like compared to the movement’s mainstream, will they be included in the process of building a new society? Is it possible to reconcile this exclusionary practice with a supposedly universal and participatory democracy?

The limits of liberal citizenship

Aside from the obvious issue that much of the city’s current ills are caused by those who hold a Hong Kong ID card (including Carrie Lam herself), the “Hongkonger” identity is often mobilized as an argument to “reclaim” the “Hong Kong–ness” of the city. This is another way to describe a liberal demand to protect civil liberties, the rule of law, and the semi-autonomy of Hong Kong; in other words, conceptualising liberation simply as resisting state encroachment on the inalienable liberties of citizens. Couching these politics in terms of identity may give them romance and fervour, but without questioning historical and structural injustice, the drudgery and soullessness of work, and the command of capital over our lives, the identity politics of the “true Hongkonger” will never be radical.

Under these politics, many Hongkongers fight for freedom of expression, but look the other way when rising rents make survival impossible for artists and cultural producers. Many fight for universal suffrage, but few fight for a universal pension; even fewer interrogate the reality that the equality of “one person, one vote” means little in the context of the increasing precarisation of work, the pauperisation of the masses and the centralisation of resources and decision-making power. Some Hongkongers treat independence as the holy grail of Hong Kong’s liberation, but rarely consider who owns the city—and whether the sovereignty they so eagerly crave will ever be in the hands of the common people, or if independence would merely substitute one ruling class for another.

Instead of a framing Hong Kong’s struggle as merely a fight for civil liberties, between free citizens and an authoritarian regime, could we also see this a fight against the dominance of the financial industry, corporate monopolies, wasteful infrastructure projects that displace rather than serve communities, the length and intensity of work, unaffordable housing, and policies skewed in favour of megadevelopers? After all, these factors have precipitated the political crisis today. This is not to diminish the ongoing violations of Hongkongers’ civil liberties, or to overlook the erosion of the Hong Kong government’s autonomy, but to suggest that it is foolish to focus the movement’s energy on simply demanding things be “restored” to the way they were before. We must remember: even in the years Beijing allowed the city more breathing room, Hong Kong was very far from being a just society. Treating civil liberties and political autonomy rather than distributive injustices as the central concerns of the current struggle shows a naïveté that liberation can be achieved without answering the social question, or that political emancipation will automatically deliver solutions to our social, economic and cultural inequalities.

The pitfalls of foreign powers

The movement has been leveraging very problematic forces for support. This started in June, with petitions to the consulates of G20 member countries, in hopes that those countries would speak up on behalf of Hong Kong. It immediately became clear that hope in those countries was misplaced: on a trade negotiations table, no country would risk upsetting the more powerful ones on behalf of Hong Kong. The only country close to being in a position to bring up the “Hong Kong problem” to China was the United States and, even then, President Donald Trump’s efforts appeared tepid at best—later followed his declaration on Twitter that President Xi Jinping “is a great leader who very much has the respect of his people” and that he has “ZERO doubt [that] if [Xi] wants to quickly and humanely solve the Hong Kong problem, he can do it.”

A more serious concern than the inefficacy of relying on G20 countries to pressure the CCP is that this tactic betrays those who suffer from state oppression under the very governments that the movement seeks to lobby. The G20 itself is a highly undemocratic, unaccountable agenda-setting body hell-bent on promoting trade liberalisation, public industry privatisation, and “structural adjustment” in the so-called Global South countries, which has often led to extremely socially and environmentally irresponsible investments by Western capital in those countries, while frequently trapping them in a state of underdevelopment.

At the same time, protests against G20 conferences have historically been met with police violence and mass arrests. Some of the G20 countries are the most repressive nations on the planet, including Brazil, whose police force has unleashed tear gas and batons on protesters going on general strike against President Jair Bolsonaro’s neoliberal pension reforms. The fires engulfing the Amazonian forest are a further indictment to the Brazilian state’s neglect of the land rights of invaded and dispossessed indigenous communities, environmental sustainability and biodiversity, all in the name of supporting large agribusinesses and economic development.

Currently, protesters are lobbying for the U.S. government to pass the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act (HKHRDA), which would mandate the United States to annually assess whether Hong Kong is “sufficiently autonomous from mainland China” to continue enjoying special U.S. trade and economic benefits, and to permit “punitive measures against government officials in Hong Kong or mainland China who are responsible for suppressing basic freedoms in Hong Kong.” Given the U.S.’ notorious track record of human rights violations and undermining democratically elected governments abroad, it is absurd to have any faith that the U.S. would actually protect Hong Kong’s democracy, rather than use the city’s plight as a bargaining chip with Beijing to serve its own economic, geopolitical, and military interests.

Expecting an ally in the U.S. government is insulting to all the people that it has harmed and oppressed. Even from a solely strategic point of view, this expectation of U.S. assistance is quite foolish, as it plays into the Hong Kong government’s and CCP’s narrative that the movement is a “foreign-backed colour revolution.” This not only undermines the fact that the movement has relied significantly on people’s own initiatives and spontaneous direct actions, but also makes it easier for the Hong Kong and Chinese governments to use it as a pretext to dismiss the legitimate concerns and demands of the movement.

Responding to police violence

Beyond anger at the Hong Kong government, the reason for the movement’s continued persistence is continued outrage over police brutality: from police’s frequent use of violence, including live rounds, their profoundly disturbing tactics (such as kettling protesters and infiltrating their ranks), their routine attempts to interfere with reporting, their apparent willingness to allow for the assault of civilians and protesters by armed mobs, their abuse and alleged sexual violence against detainees, etc. The list is not exhaustive, but it points to a fierce indignation at police brutality and abuse of power, shared not just within the movement, but amongst members of the more “passive” public as well.

The movement has responded in several ways, including an information campaign on police brutality whereby photographic and textual evidence is collected and disseminated via social media and Lennon Walls. Some citizens have even organised neighbourhood screenings of video documentaries on certain key incidents, such as the “Siege of Citic Tower” and the “Yuen Long Station terrorist attack.” Lately, the focus of the protests has extended from the four remaining demands to holding the police accountable for specific instances of abuse. For example, some protesters organised a sit-in against suspected police-mob collusion, pointing to the fact that no action had been taken in the month since the July 21 armed attack at Yuen Long Station. There has also been a #MeToo rally condemning sexual violence against protesters by the police. A sixth demand, to “disband the police,” has also gained momentum.

Recent protests have followed a similar sequence of events: A rally begins with protesters largely following the designated path. Eventually, protesters spill out into roads and areas not originally allocated for the rally, usually because the police had created artificial constraints or had banned the protest altogether. Many protesters stay in the area until late in the evening, continuing to chant their demands and build barricades as they anticipate police action. The police then deploy anti-riot squads to disperse the protesters; the more bellicose protesters engage in guerrilla clashes with the police on the front lines, while others hang back to provide support. As the night goes on, the police amp up their efforts and start to go after protesters for arrests, often subduing them with grossly excessive force and even arresting non-participant onlookers. Things eventually die down for the night, and the sequence repeats with the next rally.

Despite the quantity and severity of the injuries and arrests, the possibility of torture in detention, as well as up to ten years in prison on rioting charges, the hardline faction of the movement still appears to have an appetite for direct confrontations with the police. This is a result of several developments since the 2014 Umbrella Movement, including a much greater tolerance for direct action—especially among the “peaceful, rational, non-violent” faction that had previously been critical of militant escalation. Protesters are no longer as worried about appearing civil or respectable; appealing to the public is now mainly the task of the movement’s media volunteers. Protesters are also increasingly prepared for arrest—whether it be it from frontline clashes or administering a Telegram group devoted to information about the protests.

The need for a turning point

On a strategic level, it is worrying to see that the energy of the movement is increasingly sapped by near-daily clashes with the police, because it is difficult to see how this battle is one the movement can win. This long, brutal fight is taking a toll on the movement, and not only in terms of injuries and arrests; the mental and emotional wounds caused by the need to “stay strong” and keep contributing—a deep sense of duty I see in many of the people I know who are involved in the struggle—while witnessing their comrades’ suffering at the hands of the police, can be just as debilitating. Young Hongkongers are being ostracised and financially cut off by their parents for participating in the movement; others have even been removed from their families by overzealous judges.

Protesters’ trauma, fatigue, and frustration mean the movement is nearing a critical point, where it is unlikely to survive in its current form for much longer. In turn, many protesters have adopted an “if we burn, you burn with us” attitude, but even then we must be realistic about how much leverage the movement has. The fact of the matter is that the government and the police have the resources to spare if they want to stall or escalate, while the movement can only last so much longer on the streets.

But this is no reason to lose hope. If the movement can articulate broader demands, widen its base and explore new angles to challenge the state and undermine the status quo, there is every reason to believe that it can gain the necessary momentum to achieve something truly transformative.

Toward a worker-led politics

Whether the movement intended to or not, it has laid bare many deep-seated social ills and conflicts. However, it cannot hope to solve them if it continues to conceptualise the struggle simply as one of “true citizens” defending their liberties. In addition to its political demands, the movement should stand against Hong Kong’s distributive injustices, the dispossession of ordinary people by the ruling real estate and financial elites, the privatisation of our commons for profit, and the government’s disregard of ordinary people and marginalised communities.

After all, this movement is also the fight of ordinary workers who work the longest weekly hours in the world, whose real minimum wage has hardly changed from when it first came into force in 2011, who do not have the right to collective bargaining, who must surrender part of their wages to a broken pension system, who remain in poverty despite working multiple jobs, and who find job security increasingly difficult to come by. It is also the fight of residents who are spending more and more on rent, who are evicted from their homes so that soulless luxury edifices can be built in their place, who see their favourite noodle places and corner shops replaced by big brands, restaurant chains and shopping malls, who cannot find affordable nurseries for their children or care services for their elders. It is also the fight of communities, who are displaced from their lands so that expensive, environmentally-damaging white elephant infrastructure projects can take their place, all while the government ignores the huge shortage of public housing.

Workers have already been directly implicated in the protests. In late August, outside Yeung Uk Road Market, the police fired more than 140 rounds of tear gas while trying to disperse protesters. During this time, cleaners employed by the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department, and outsourced to Johnson Cleaning Services, were ordered to continue cleaning in the market even though tear gas seeped in through the windows and the ventilation system while they were working.

Afterwards, the cleaners were ordered to carry out a deep cleaning of the market over two days, to eliminate residues of the harmful chemicals. Images show that the cleaners had only minimal protective equipment. They were only given very basic masks and plastic gloves, and their uniforms did not fully cover their arms. Their equipment was totally inadequate to protect them from inhaling or touching tear gas residue, a noxious substance which can cause chest pain, nausea, and chemical burns in the nasal cavity, the bronchi and on the skin. Upon questioning, a representative of the Tsuen Wan District Environmental Hygiene Office had no knowledge of the risks of exposure to tear gas residue or what protective equipment would be needed for those cleaning tear gas residue. It is safe to assume that the cleaners were not informed of the risks they would be exposed to nor given training or guidelines for cleaning up toxic chemical material.

Whether the movement intended to or not, it has laid bare many deep-seated social ills and conflicts.

While the Department and outsourcing company’s callous disregard for the cleaners’ health and safety is appalling, it is by no means an exception. Our economy relies heavily on workers, who are paid very little, employed on temporary contracts with minimal benefits and under conditions that leave much to be desired, to pick up the pieces, tidy up messes and ensure business continues as usual. Protesters were rightly enraged by what these cleaners were forced by their employers to endure, but this anger should not stop there. These are the kinds of occupational hazards and rote tasks that underpaid workers at the base of society are forced to endure every day. It would be disingenuous of the movement to take issue only with the treatment of cleaners in this situation while turning a closed eye to their working conditions generally.

Reprisals against workers

Workers’ precarious position has been made doubly evident by a recent spate of protest-related dismissals. Multiple airlines sacked staff members during the wave of actions that paralysed operations at Hong Kong International Airport. Most notably, Cathay Pacific has fired 30 staff members, including eight pilots and 18 flight attendants, since the Civil Aviation Administration of China warned the airline not to allow staff members who support the movement to work on flights passing through Chinese airspace. The Chairperson of Cathay Dragon’s Flight Attendants Association Rebecca Sy was fired after being interrogated about her social media posts supporting the movement. The dismissal of Sy, a trade union leader, was particularly suspect because Cathay Pacific had just implemented a new mechanism to calculate average daily pay which would mean large decreases in holiday pay. This new mechanism was introduced without negotiating with rank-and-file workers or the Hong Kong Cabin Crew Federation, to which Sy’s union belongs. By dismissing her, the airline may have been trying to mitigate union opposition to their new pay scale. The Federation has since convened an extraordinary general meeting to discuss the possibility of organising industrial action and hiring Sy to become its General Secretary.

But these kinds of reprisals against employees have been ongoing; Hong Kong’s labour organisers have long faced similar retribution. Over the years, many workers have faced unreasonable dismissal for fighting for their rights or raising legitimate workplace concerns. Other workers have been dismissed so that employers can avoid compensating them fairly. Just last year, piano tutors for Tom Lee Music were pressured to give up their permanent employee status and take up self-employed contracts—with less stable working hours and pay, and the loss of their pensions, paid leave and medical insurance. A group of tutors who refused to become self-employed were then completely frozen out of the business by Tom Lee; some of them had to work part-time at McDonald’s or as security guards on the MTR just to make ends meet. Yet many workers are fighting back boldly, including Sai Fai, a chef who began labour activism in 2003, and has been blacklisted and refused employment by some of the city’s biggest restaurant and catering corporations because of his union work, including the founding of the Hong Kong Chef’s Union in 2015. In 2017, while working for Lufthansa, he managed to accost Carrie Lam over her anti-labour policies in person; the next day, his manager showed up, complained that he had not included vegetables in his pork and egg rice, and fired him.

Conclusion

All of the issues I have named are potential opportunities for the movement to start integrating social and economic issues into its programme and to make class-based demands against the state. To overcome the cultural and ideological hegemony of liberalism as the dominant mode of political participation in the movement and Hong Kong’s broader society, we must articulate demands that speak to people not only as citizens stripped of rights and liberties by an authoritarian state, but as working people increasingly dispossessed of their means of survival by an economic structure that serves the interests of ruling elites. This speaks to the need for a grassroots- and workers-based internationalism to counter right-wing tendencies within the movement.

The connections I have made between civil-political and class-based demands are rooted in a personal anxiety that if a movement of this scale cannot shake up our deeply unequal and unjust social fabric, then nothing ever will. But there is also obvious sense in articulating broader demands. While some have argued that this would make the movement lose focus, I argue it would actually provide more avenues to mobilise and more ammunition to attack the state and its cronies. For example, if the movement raises labour issues as part of its concerns, then it would be in ordinary workers’ material interest to support a strike—making it much more feasible to organise a sustained and successful general strike. This could be one of the most powerful tools the movement has.

Parting thoughts

No social commentary should conclude without concrete calls to action, so here are some ideas for additional demands that could increase the movement’s power:

- Defend our commons: bring Link shopping malls back under public ownership and control; stop marketising public housing units; abolish the Land (Compulsory Sale for Redevelopment) Ordinance allowing property developers to evict tenants and “redevelop” establishments with “compulsory purchase” once they acquire 80% of the title; increase budgets for district councils whose use will be democratically planned.

- Defend workers’ rights and dignity: implement a living wage and standard working hours; reinstate sectoral collective bargaining; abolish the offsetting mechanism in the Mandatory Provident Fund that allows employers to shirk the responsibility to pay severance; abolish the “418” continuous employment rule that undercuts temporary workers’ basic rights; abolish the “live-in rule” and “two-week rule” for migrant domestic workers and allow them to negotiate and contract with employers directly; end the outsourcing of public sector workers.

- Distributive justice: implement a progressive income tax, land value tax and vacancy tax on empty properties; stop the use of land auctions as a source of government revenue; use brownfield land and other unused land for public housing; put more resources into public hospitals (more space for more beds, better pay for public hospital staff, etc.) and care services to relieve the work of unpaid carers.

- Stop white elephant projects: put “strategic infrastructure” projects that do not serve the needs of local communities and people in Hong Kong on hold, including the East Lantau Metropolis/Lantau Tomorrow development, reclaiming land for a third airport runway, and the Wang Chau green belt development.

And two tactical suggestions:

- Support the trade union movement and agitate for a general strike. Establish a strike fund to pay for the living expenses of those participating in the strike; unwaged and precarious workers have priority. If we can raise enough money to have front-page open letters on international broadsheets, we can raise enough money to support one another. In particular, agitate for airport ground handling staff and airline crews to go on strike to maximise disruption to international travel.

- Fight in solidarity with movements in Mainland China and across the world struggling against the CCP, whether they are lawyers and activists in Guangzhou, Uyghur Muslims in East Turkestan, or the people of Kyrgyzstan resisting China’s neo-colonialism via its One Belt One Road initiative.

None of this is to diminish the accomplishments of the protesters so far. Instead, I believe that adjusting strategies and recalibrating demands as events unfold is natural for social movements. This is simply an appeal for the movement to continue to examine its limits and reflect on how it can improve so that ultimately, it can win.