Original: 【外國勢力的配對哲學】, published in 明報 (Ming Pao)

Translators: Promise Li, LWH, P

If you would like to be involved in our translation work, please get in touch here.

Translators’ note: This critique of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act (“HKHRDA”) by Au Loong-yu, a long-time Hong Kong labor activist and researcher, is tailored to the everyday Hongkonger who is not a part of the left. 配對哲學 is a kind of neologism: Au encourages the readers, who may not be well-versed in anti-imperialist or geopolitical analysis, to think of these paradigms as a “philosophy of matching.” To “turn the tables back” (“玩翻轉頭”) on Beijing’s strategy of presenting the protests as directed by foreign agents, Hongkongers must understand the geopolitical dynamics of how different imperial powers “match” with each other (“外國勢力的配對哲學”) and play by the same script (“串連國際和北京唱對臺戲”).

This language of “matching” works two-fold: one, to critique Hongkongers’ petitioning the U.S. through the HKHRDA as a “bad match,” and two, to open up dialogue about what forces Hongkongers can match with to promote genuinely progressive social change, and find an opening out of the moment’s crisis. This realpolitik approach ultimately makes room for a powerful critique of the contradictions of Hongkongers’ uncritical support of the bill: “Is helping a foreign government persecute its own dissenters the original intention of the anti-extradition movement? Wasn’t our original intention opposing extradition policies that violate human rights?”

Au builds toward an anti-imperialist critique of this petitioning movement by pointing out the clear contradiction that supporting the bill, with all the elements that entangle Hong Kong with U.S. foreign policy, would go against the very raison d’être of the whole anti-extradition bill movement in the first place: the city’s autonomy in its rule of law. Au further reminds the readers that Hongkongers had been protective of Edward Snowden, during his brief sojourn in the city, from U.S.’s demands for extradition just years ago. Au does not impose theory from above, but rather “matches” and connects the protestors’ existing desperations with their pragmatic mindsets and past experiences, in order to find the opening for an anti-imperialist critique of U.S. power.

But what makes a good match? In other words, what types of links of solidarity should Hongkongers develop in order to cultivate a mass politics that would not be a relapse to bondage? Au’s article suggests that the key to liberation for the current movement is for the protestors to find and match with the right partners and allies, and not gives cues to the wrong sorts (“認錯朋友表錯情”). The possibilities are manifold if we look away from the U.S. Consulate and other global elites: the disenfranchised workers in the Mainland, the transnational left, Hong Kong’s own migrant workers, etc.

To read Lausan’s analysis of the HKHRDA, please click here.

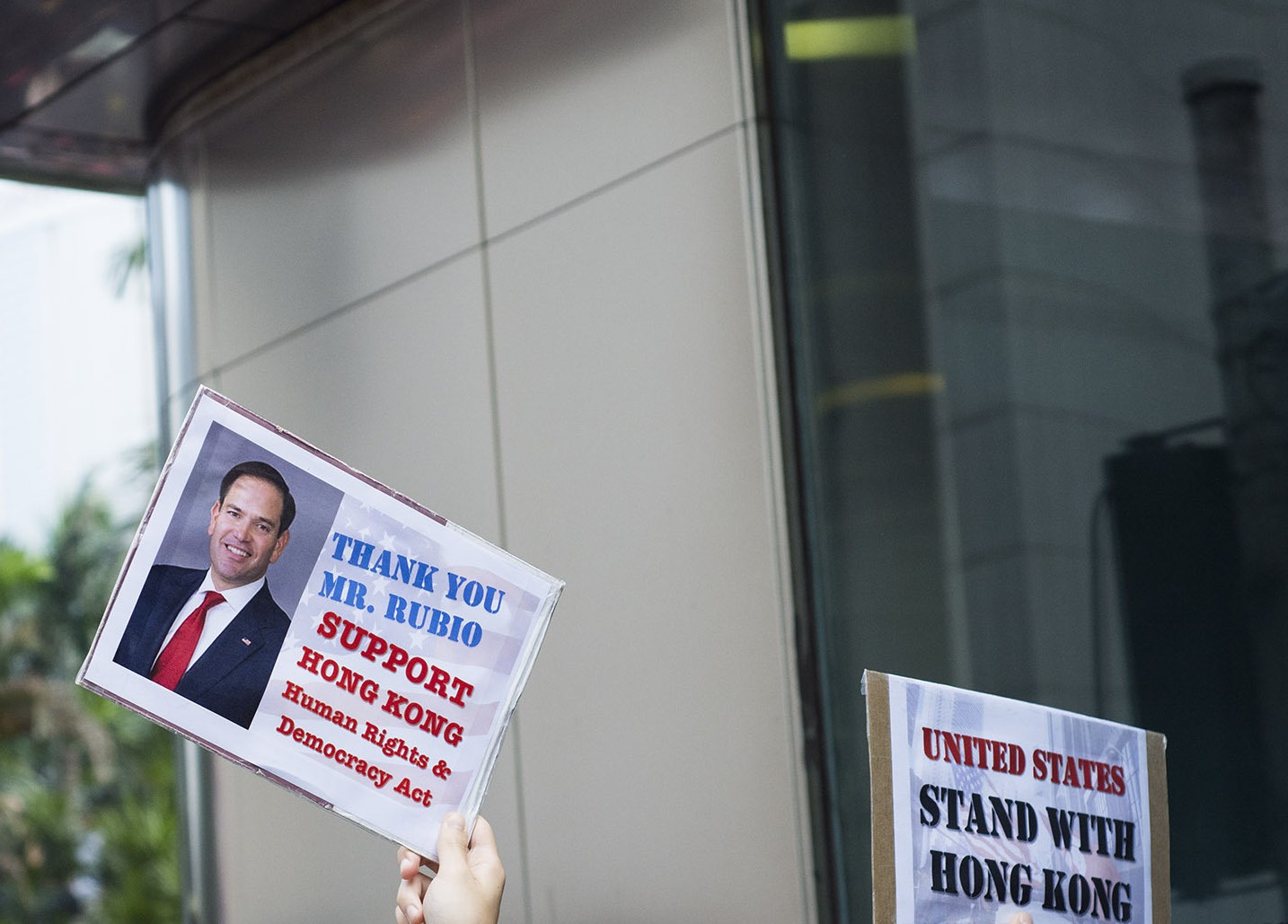

Last Sunday, people marched to the U.S Consulate in Hong Kong to ask that Congress pass the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act. At the same time, Beijing continued its accusations of “foreign intervention.” But in reality, Beijing itself does not prohibit all foreign interference; it is simply highly selective as to which ones work to its interest. It deeply understands the “matching game” of international politics, knowing to rope in dictatorships like North Korea to cheer for itself. Similarly, China and the U.S.’s dynamics fluctuate between soft and harsh rhetoric, with China only clearly leaning on the latter when it comes to suppressing some rebellious small region.

Hong Kong still has British police officers

But, on the point of “foreign power,” the tables may quickly turn on Hong Kong. I was having a casual conversation with some friends, and one said: “Every time that white British police chief Neil Burnett beats the protesters up, that’s ‘foreign interference.'” Another one followed: “Isn’t it the same when Carrie Lam included five sympathetic international experts to join the police inquiry commission?” Beijing does not mind these foreign interferences one bit.

How are the tables so easily turned on Hong Kongers? Because “One Country, Two Systems” is itself a product of negotiations between Deng Xiaoping and other foreign powers. The Basic Law is the result of collusion between Deng and our so-called enemies. The Basic Law protects British and American interests first and foremost, whether it is the continued usage of English as an official language; the persistence of the common law system; the appointment of foreign judges to Hong Kong courts; the granting of UK passports to Hongkongers; or the institution of Article 101, which guaranteed that British nationals and other foreigners would be able to maintain their positions as civil servants or government consultants, leading Burnett to have the ability of beating us Chinese up. Beijing’s promise of “One Country, Two Systems” allowed foreign influence to fester in the city from the start. But some of these same structures have given Hong Kong civil society the leverage to voice their concerns. They can turn the tables back around by understanding that, in reality, the “foreign powers” and Beijing are operating from the same script. This is the prerogative of both Beijing and Hong Kong; however, Beijing has long distanced itself from Deng’s legacy.

Is it a disaster to cultivate relationships with the Japanese far-right?

If civil society wants to flip this accusation of “foreign interference” on its head, they need to ensure that they understand the game of alliances in international politics. The LIHKG post “Before mindlessly praising the Japanese, remember to fact check” is one such example. The netizen argued that Suzuko Hirano’s support of Japan’s actions in the Sino-Japanese War during her appearance at last week’s citizens’ press conference was in line with the most extreme factions of the Japanese far-right.[1] The LIHKG user also argued that the Japanese public generally do not like the far-right. If we associate with them, it will be to our own detriment.

To right-wingers, this is not bad news, but rather a boon. In recent years, an interesting contradiction has appeared—namely that of extreme nationalists ironically positioning themselves as “internationalists” and actively seeking out opportunities for collaboration. These extremists believe such alliances are sound. However, if you are not an extremist, or you have not given this situation much thought, you might put a foot wrong and be hoodwinked.

In early August, some local media outlets described Suzuko Hirano as “someone who is always willing to help clean a Tokyo shrine for a sacrificed Japanese soldier.” Since Hirano did not want to upset Hongkongers, she was not willing to reveal the name of the shrine. It can be deduced from her blog posts that the shrine in question is the Yasukuni Shrine.[2] As part of the Yasukuni Shrine Admiration Committee, Hirano helped organize an educational event about the Battle of Leyte, which resulted in 80,000 casualties for the Japanese—half of whom died from starvation. The majority of those who died were low-ranking soldiers (many of whom were sons of farmers) and less than 500 people survived. In addition, one million innocent civilians from the Philippines also died.

Beijing’s promise of ‘One Country, Two Systems’ allowed foreign influence to fester in the city from the start. In reality, the ‘foreign powers’ and Beijing are operating from the same script.

However, Hirano wrote that she was grateful to the military for guarding Japan. Good god—to completely gloss over the victims of the conflict and to express gratitude to the perpetrators! This is an imperialist and militaristic view of history—not one rooted in democracy and peace. Support of Hong Kong’s anti-extradition movement from people like Hirano only serves to support their imperialist and militaristic interpretation of history, as well as their propagandistic rhetoric concerning China’s imminent invasion of Japan. If you’re not on the far-right, and yet uncritically share the news that Hirano supports Hong Kong, it is possible that you’ve cultivated a relationship with the wrong ally.

Even worse, those even further right than Hirano held a rally in support of Hong Kong on September 8—something which was warmly received by Hongkongers. The organizer of the rally was Satoru Mizushima, a famous right-wing conservative television producer. Foreign media have previously reported that he denies the Nanking Massacre. He has also previously led teams to occupy the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands to demonstrate Japan’s sovereign ownership over the islands. My doubts about Mizushima can be summarized as follows: He argues that China annexed the islands—but Okinawa Prefecture, which has jurisdiction over the islands, was also occupied by the United States and its military. Mizushima remains silent on the issue of U.S. occupation and instead denounces the Okinawans for their opposition to U.S. military activities and imperialism. So which brand of Japanese nationalism is this?

I was part of the Protect Diaoyutai Islands Movement in my youth, but in the past ten years or so, I’ve found myself agreeing with Mok Chiu-yu’s view.[3] Mok argues that the islands should belong to the fish and not to any one country. Neither Mizushima’s view nor Zhongnanhai are my cup of tea. It is neither right nor wrong to appeal to foreign countries. No matter our ideology or stance, we tend to engage with those who share the same views as us. Different strokes for different folks. But the worst thing is not understanding and unknowingly engaging with people outside Hong Kong.

Would you even support sanctioning Iran?

Last week’s mass-led petition to the U.S. Consulate was another example of mismatched geopolitical alliances. Hong Kong media’s reports on the HKHRDA piqued many people’s excitement. But these reports obscured many important facts. This bill actually does not only entirely relate to Hong Kong’s human rights and democracy; this name is rather misleading. First, in Section 3, the bill is very clear with its aim: it is because the U.S. has interests in Hong Kong that it is intervening—to defend its own national interests. Of course, U.S. interests may overlap with those of Hongkongers right now (this is not surprising under the Basic Law), but they do not completely overlap. Therefore, they remain two distinct spheres, with the chance of contradictions. For example, Section 5.a.6 demands an assessment of whether Hong Kong sufficiently enforces U.S. sanctions on certain nations or individuals. Reasons for sanctions include punishing countries or individuals involved in “international terrorism, international narcotics trafficking, or the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, or that otherwise present a threat to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.”

This is clearly aimed at protecting U.S. national interests, not defending human rights and democracy for Hongkongers. The definition of what constitutes as U.S. national interest will always fall on the U.S. government. Taking a step back, this reveals bigger issues. Like “the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction”—the U.S. claimed that Iraq had these back in 2003, and claimed that it had the right to seek vengeance on those doing business with Iraq and its constituencies. Ultimately, the U.S. did not discover any weapons of mass destruction in Iraq—by that point, Iraq had already been ravaged, with countless civilian deaths. The U.S. continued to operate with impunity—do these constitute violations of or respect for human rights? Should Hong Kong pro-democracy activists unconditionally support this bill even if it would further ensnare Hongkongers in U.S. foreign policy? Different strokes, different folks. If you’re one of those who think that the U.S. government only does good things and completely support its foreign policy, then it is natural that you would support this bill. But if you are not one of these people, or if you haven’t even read through the bill, and yet profess your unconditional support for it, aren’t you making the wrong allies?

This bill also includes mandating the Hong Kong government to sanction North Korea and Iran. Are we also now deciding to sanction Iran? Even many countries in Europe are refusing to follow the United States’ move to abandon the nuclear agreement with Iran, since this is clearly Trump’s attempt at being provocative. Must Hong Kong’s anti-extradition bill movement help the U.S. enact its foreign policy too? How does that benefit us? Our opponents may respond to our critiques by saying that, be it right or wrong, the U.S.–Hong Kong agreement on extradition policies have already been set in place before this bill. Since that’s the case, why does the U.S. need to repeat these conditions in the bill? If it is that important to repeat these conditions, then why not rename the bill, and not mislead the public into thinking that the bill is solely concerned with Hong Kong human rights and democracy? From the standpoint of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong, why should we be forced to stomach the bill, both its benefits and its drawbacks?

Snowden escaping to Hong Kong

Also, the bill’s Section 6.c.1.A “assesses whether the Government of Hong Kong is ‘legally competent’ to administer the United States–Hong Kong Agreement for the Surrender of Fugitive Offenders.” Although this section primarily targets protecting U.S. citizens in the case that the extradition bill passes, its actual boundaries of inclusion are actually quite large, including the right to compel Hong Kong to extradite U.S. “criminals,” such as Snowden and Assange. Do not forget: in 2013, the U.S. tried to make Hong Kong extradite Snowden. Fortunately the government did not comply. In reality, many in Hong Kong supported Snowden’s right to seek asylum in the city, since this is a basic human right. At this year’s G20 summit in Osaka in June, due to the efforts of international civil society groups, like Civil 20, to push G20 governments to offer further protections for whistleblowers, even the G20 vaguely affirmed that whistleblowers are key to ending corruption.

Should Hong Kong pro-democracy activists unconditionally support this bill even if it would further ensnare Hongkongers in U.S. foreign policy?

U.S. senators continue to reaffirm its extradition policy in the bill, while expecting Hong Kong to comply with its sanctions and offer no guarantees to protect whistleblowers. This is not respect for human rights. On the contrary, the bill will help the U.S. government prosecute its whistleblowers. Is helping a foreign government persecute its own dissenters the original intention of the anti-extradition movement? Wasn’t our original intention to oppose extradition policies that violate human rights? If so, how can we accept these conditions, and even petition the U.S. to pass the bill without any amendments? If U.S. congresspeople are truly devoted to Hong Kong human rights and democracy, then why would they tie our demands to U.S. foreign policy and extradition policies?

Different strokes for different folks

By asking the questions above, I hope to open a space for questioning within the pro-democracy camp. It goes without saying that there are multiple explanations and definitions of democracy. These questions involve different political positions and approaches—Hongkongers are not used to talking about these issues. However, engaging in international politics without discussing political positions and ideologies is misguided. This is not an ideological debate but rather a question of understanding international politics. Don’t forget—the United States’ national interests are not the same as the best interests of the Hong Kong people. After all, the United States suddenly changed course and abandoned the Republic of China government in 1971–1979—or have we forgotten that?

Footnotes

[1] Suzuko Hirano is a Japanese model and actress who has been supporting the anti-extradition protests. https://japan-forward.com/interview-japanese-actress-and-model-suzuko-hirano-on-why-she-supports-hong-kong-protesters/ (@suzutaro18 on Twitter)

[2] Located in Tokyo, the Yasukuni Shrine commemorates Japanese soldiers from 1869–1954. The shrine also commemorates 1,068 war criminals, 14 of whom are categorized as Class A war criminals.

[3] Mok Chiu-yu is the founder of the Centre for Community Cultural Development. A relatively well-known anarchist in Hong Kong, Mok helped found “The Seventies Biweekly,” which spoke for the radical youth voices in early 1970’s Hong Kong.